Is This Legal?

The Is This Legal? smartphone app. provides users with easily accessible and transparent information about legal systems they are subject to in their current, geotagged location – complicating users’ readings of foreign national identities.

Fig. 1 Is This Legal? Logo.

ITL’s concept arose from brainstorming, where we became interested in geotagging – used to provide users with information customised to their geographical location. Originally ITL focussed on open container/public drinking laws, however we soon realised this was too specific and decided to widen our scope.

After establishing there were no app’s similar to ITL on Google Play & iTunes – deeper research into design and academic discourses began.

Google Docs became our digital workspace, allowing us to conduct work in ‘real-time‘ even when individual members were working remotely/separately. Using a web-based document meant our group could work on the same text simultaneously – across multiple computers. Common group work issues were avoided e.g. repeating work, creating multiple drafts etc. Additionally Google Docs allowed the group to read, edit and critique individual member’s work, ensuring all writing underwent rigorous editing.

Fig. 2 – Google Docs Project Proposal.

New media is best researched using new media: UvA’s open catalogue search engine, resources like JSTOR and SAGE Publications provided helpful works from tourism studies and sociology. Researching exclusively through new media helped us find multiple sources, although discerning which sources were useful was difficult. Print sources are harder to scan for relevant material, but search engines are no real substitute for a librarian. The ‘window shopping’ research stage was therefore much faster using new media, but deeper readings were notably harder due to the ‘overload’ of material.

John Urry defines the Tourist Gaze as:

“People [who] gaze upon the world through a particular filter of ideas, skills, desires and expectations, framed by social class, gender, nationality, age and education. Gazing is a performance that orders, shapes and classifies, rather than reflects the world”(2).

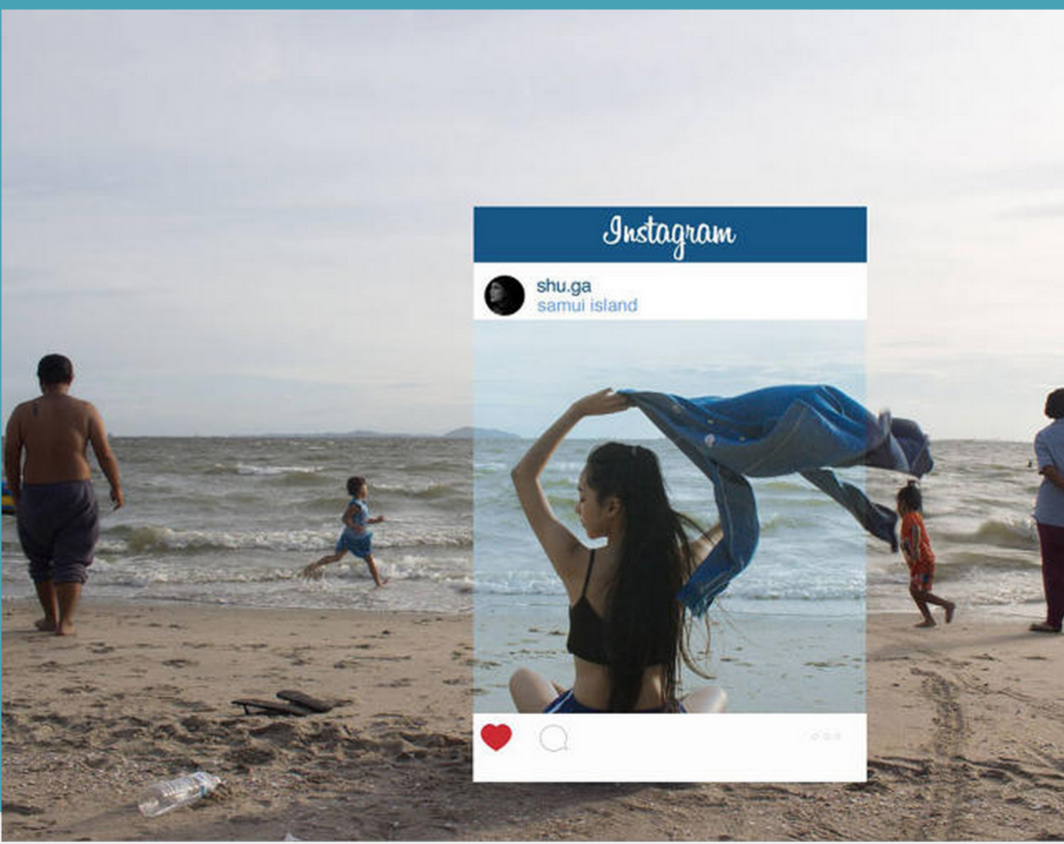

A new media example of the Tourist Gaze is Instagram, specifically the filter feature – an image’s colour palette (contrast, intensity, tone etc.) is edited – altering the image’s indexical value.

Fig. 4 – The Tourist Gaze In Action.

This image is serving viewers beach holiday realness, a woman alone in a sunny, warm seaside setting -the cloth she holds undulating in the gentle breeze.

The expanded image shows grey skies, a discarded plastic bottle and other people running cross-screen. The image’s implied island idyll narrative is revealed as false, the people running past, the rubbish and primarily the grey colours of the sand, sky and sea now read as colder/less attractive.

Fig. 5 – A ‘defiltered’ expansion of the original photo.

Urry says “the concept of the gaze highlights that looking is a learned ability and … the pure & innocent eye is a myth”(1), therefore this filtering was no naïve act. All tourists (to one degree or another) are aware they are propagating fantasy narratives using images, posts, videos, even forecasts. In the same way defiltering the image helps resist the Tourist Gaze’s censorship of foreign narratives, ITL devalidates inaccurate narratives users misread about foreign legal systems (and cultures).

For example, tourism narratives cast Brazil as welcoming, paradisiac and culturally vibrant. When arriving in Brazil, users would be alerted by ITL that the Brazilian government requires foreigners to carry identification at all times , failure to provide said identification could then result in arrest.

ITL exposes users to legal information the tourist industry actively tries to conceal. ITL would help users become more aware not only of their own role as tourists, but of how the tourism industry constructs exoticised and misleading narratives. International marketing campaigns and social media are both used to propagate commercialised narratives of Brazilian identity – making tourists less socially aware and incapable of reading Brazil’s ‘unedited’ identity narratives.

ITL works best as a smartphone app, resisting the Tourist Gaze’s normativising censorship within the smartphone’s intermedia. Smartphones contain digitalised versions of medias used by the Tourist Gaze: cartography/GoogleMaps, photography/Instagram, travel writing/social media. As part of the smartphone’s intermedia, ITL resists the Tourist Gaze within the operating system itself.

Group smartphone use not only encouraged faster communication, but significantly allowed for communication on multiple levels: Instagram, Facebook Messenger and Google Docs allowed us to communicate in more informal registers. Creating multiple lines of communication allowed us to communicate both more socially and more intellectually, bonding team members together.

Initially we considered using development software like Invision and Moqup but due to the group’s lack of experience creating a ‘demo’ version seemed overly laborious (and expensive).

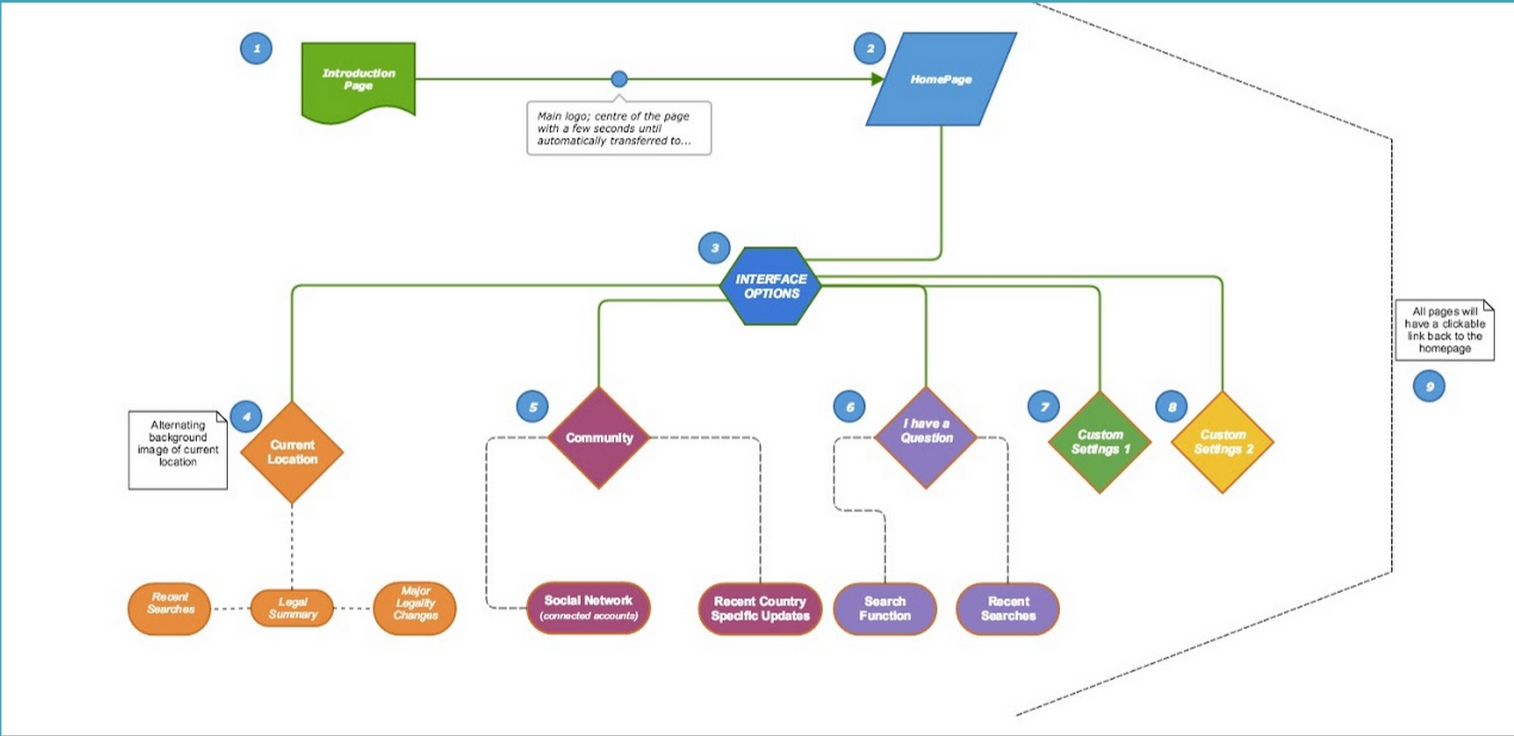

Using Gliffy, the group mapped out ITL’s different pages, and how users would navigate between them.

Fig. 6 – ITL’s Navigation Map.

Using our own smartphones the group examined different graphic interfaces for design inspiration. Growthribe, Minimums and Yahoo Weather (among others) offered interesting ways to design our layout.

Fig. 7 – ITL’s Design Mood Board.

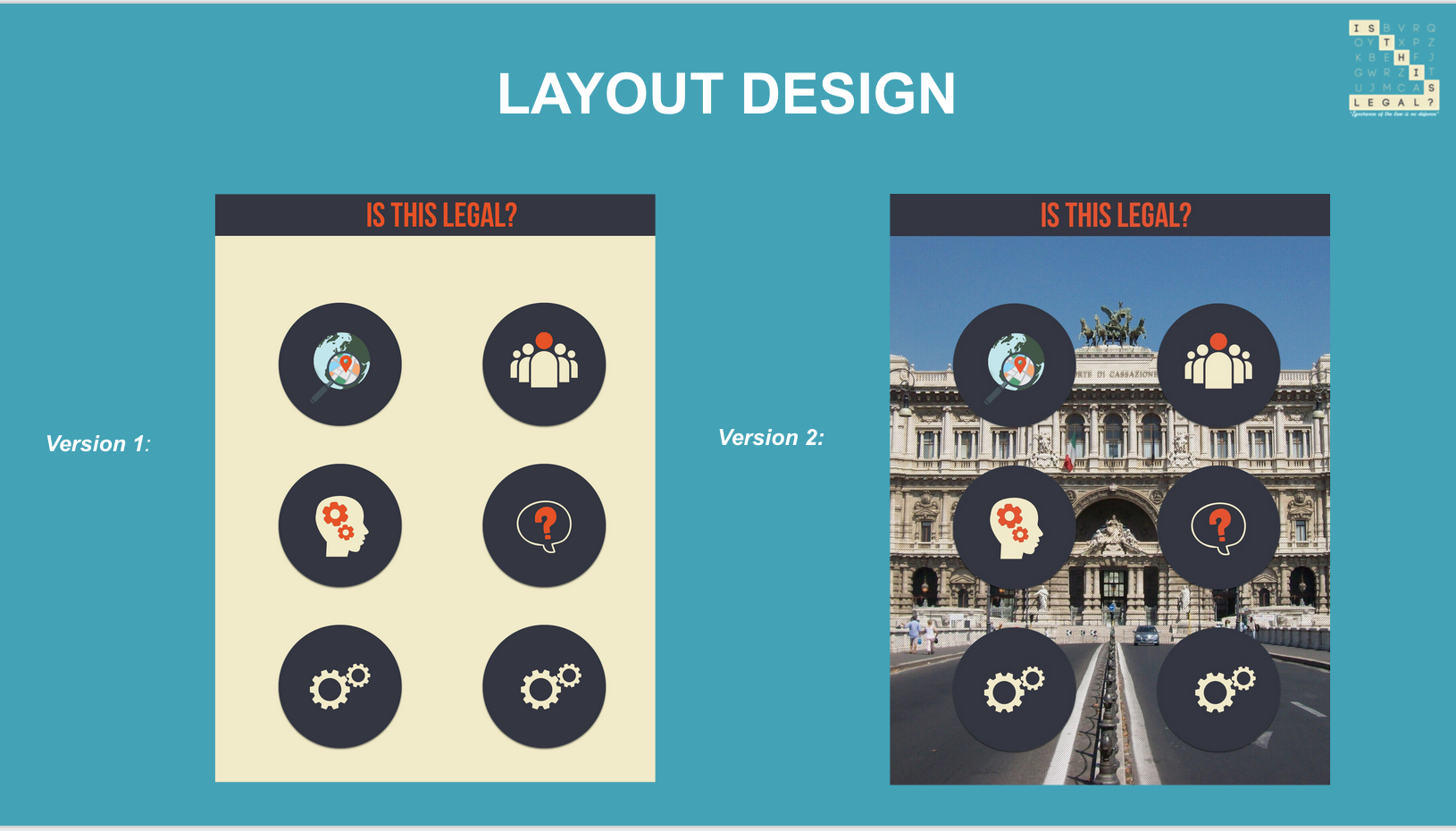

Our template page underwent revision as we tried to create a ‘user-friendly’ layout in order to make legal information as accessible as possible.

Fig. 8 – Layout Design Drafts.

During development we constantly reassessed our layout to ensure the design reflected the project objective (easily navigated/comprehensible) in our final version.

Fig. 9 – ITL’s Final Layout Template Design.

ITL’s different features provided multiple user access points for finding information. The top left tab allows users to check out legal info. summaries of any country. The top right is a community tab to link to social media. On middle left users can create a profile to customise what they receive alerts about. On middle right the ‘Ask Me Anything’ feature lets users ask any question, searching through a database of FAQ‘s to find more ‘niche’ legal info. The bottom two tabs are customisable to particular legal concerns e.g. traffic laws.

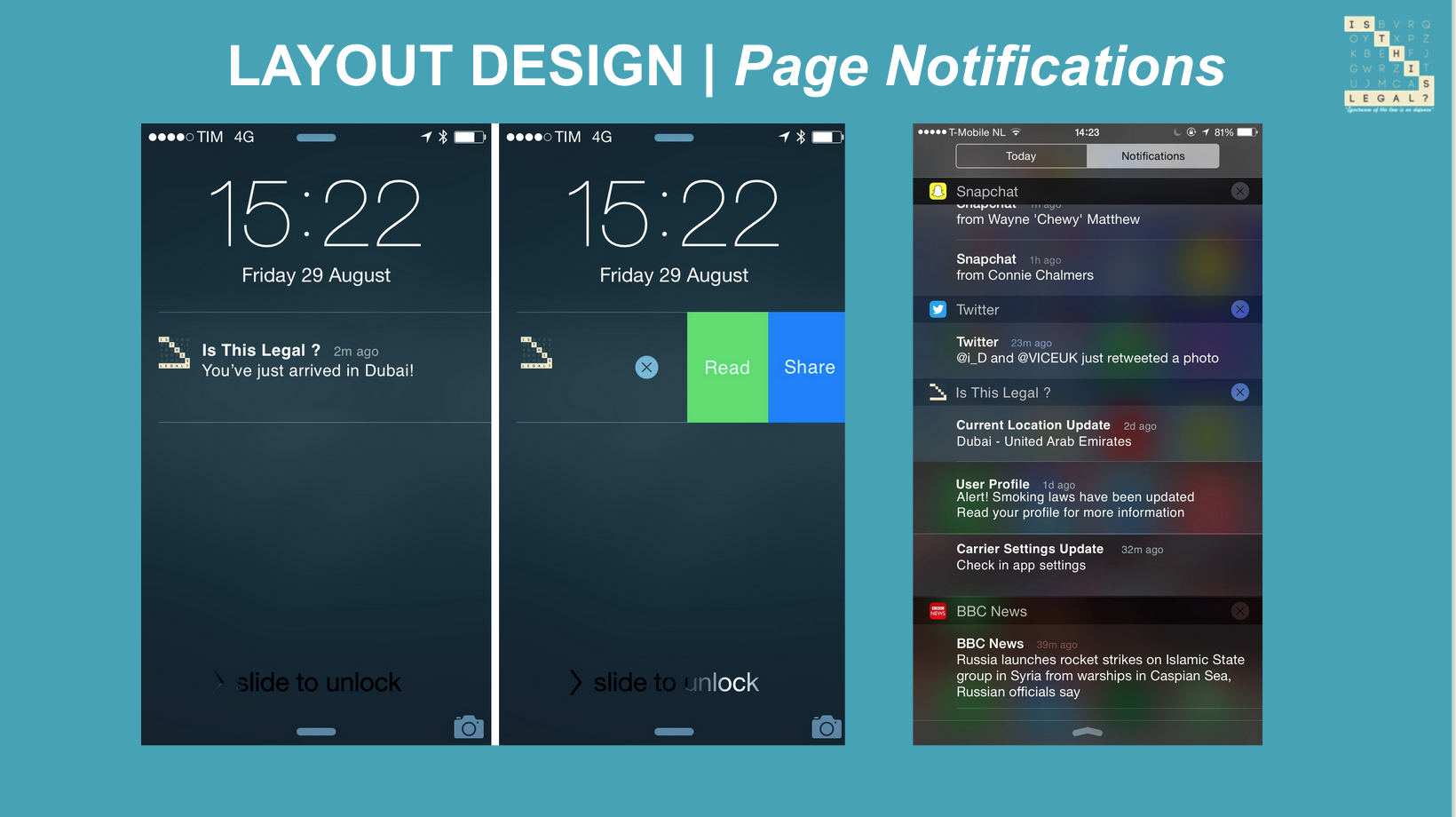

Fig. 10 – ITL’s Notification Feature.

Fig. 11 – ITL’s Opening Page.

Fig. 12 – Legal Summary Example Page – Dubai, UAE.

Fig. 13 – ITL’s Ask Me Anything Page.

If ITL were launched, it could source legal information from government e-resources e.g. E.U. Transparency Portal. Users would likely combine Couchsurfing and/or Airbnb with ITL to escape limiting/limited normative tourism mechanics. ITL‘s conceptualisation/design accomplishes its project objective, although certain material elements (programming/API’s) cannot be fully realised with mockups. Were sufficient numbers to begin using ITL, tourist communities would become self-critical on levels rarely examined by most. ITL could incite tourists to examine the power relation between themselves, foreign narratives, and the versions they read/reproduce within digital culture.

Works Cited

Urry, John. The Tourist Gaze: Leisure and Travel in Contemporary Societies. London: Sage Publications, 1990. Web.