Digital Activism, Revisited.

At the end of March, 2012, I attended the Unlike Us conference, organized by the Institute of Network Cultures. What followed was a series of conferences and insightful discussions. Unlike Us brought together activists, academics, students whom all discussed a variety of topics ranging from the economization of social media networks to cyberactivism.

The latter was my primary focus and I looked forward to the panel in which Philip Budka held a talk on indigenous cyberactivism in Ontario, Canada.

.

I have a particular interest in online campaigns targeted at the mobilisation of individuals. In the recent past, I have often focused on non-western cultures involved in online campaigns dealing with political and / or social injustice. However, my focus is not only aimed at participatory cultures as seen within blogospheres such as that of the citizen media site Global Voices, but also within fansites like the Harry Potter Alliance. Global Voices promotes a blogosphere in which the production and aggregation of semi-journalistic writings are crucial to the community. Meanwhile the Harry Potter Alliance adopts creative uses of metaphors to promote social injustice and important causes. According to Jenkins, Slack and with him the Harry Potter Alliance, found a multitude of methods, applications and campaigns to channel and mobilise members from within the Harry Potter Alliance. In this process they not only manage to engage predominantly young Americans with topics like the Darfur genocide, but they also form powerful campaigns. Such campaigns are influential, and the mixture of participatory in tandem with popular culture makes groups like the Harry Potter Alliance a rich object of study. In so doing, writes Jenkins, a new kind of media literacy is created —

“One which teaches us to reread and rewrite the contents of popular culture to reverse engineer our society. One can’t argue with the success of this group which has deployed podcasts and Facebook to capture the attention of more than 100,000 people, mobilizing them to contribute to the struggles against genocide in Darfur or the battles for worker’s rights at Wall-Mart or the campaign against Proposition 8 in California.” (Henry Jenkins)

Yet, I do like to stress that I side with Philip Budka as I prefer critiqueing cyberactivism and then especially emphasizing their sociocultural practices in relation to internet media technologies. Within this regard, even citizen journalism as practiced by Global Voices Online, Indymedia and others like movement.org.

Though, I do think that a brief allusion to the history of digital activism, could support this point.

In Retrospect: Online Communities and their digital activism under Scrutiny

The year 1994 marks the first recorded event in which social movements added new media to their activist ‘strategy and agenda. The Zapatistas became the first digital activists whose form of resistance included the integration of new media tools to optimize their strategies and local operations. At first, the movement was formed to call attention to the plight of predominantly poor, indigenous residents in the Chiapas region. Their campaign, though limited in access to computers and the Internet, was successful and gained worldwide attention. After the battle of Seattle in 1999, the Independent Media Center, or Indymedia, began its practice of citizen journalism. Here any citizen on the planet could read and write what they deemed significant (Kahn and Keller; 2004). Indymedia was a pioneer in the field of digital activism, as its social make-up consisted of an arrangement of bottom-up and decentralized online activism. Other famous examples of digital activism followed each other up quickly. These included for example the Kenyan Election protests in 2008, the Iran Election protests in June 2009, and the leaked distribution of the Wikileaks archive as of April 2005.

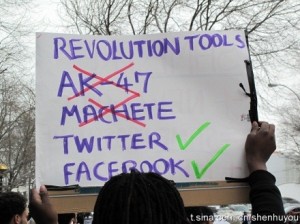

But the true winning year was 2011. In this year, movements like the protesters in the Arab Spring, the Indignados and Occupy Wallstreet played an influential role as they showed that not only was online space useful to express their disapproval with their governments, it was also a space where they could find others dealing with the same issues. Like the Zapatistas, these activists organized themselves online and consequently met on the streets of countless cities to physically and communally chant their disagreements.[1] These protests attracted a great deal of attention from the mainstream media due to their related activities on social networking sites and online debates.

Why Digital Activism?

Culture is what makes us who we are as we engage with one another in a variety of different ways. The web, in my opinion, has brought about a major shift in our experience of time, space/distance and perceptions of news. Social connections made online are thinning the wall between what’s real and what’s digital. These connections are also leading up to rich online archives, newsarticles and information, made by individuals for individuals to read, comment on or act upon. It changes the dynamic of the medialandscape.

Although the web has been experienced as a positive change to many, that does not necessarily mean that the sun is always shining. In many countries, even the United States, Internet freedom is experiencing much turbulence. The public outroar regarding certain policy strategies like the recent SOPA/PIPA act inthe US and lack of human rights issues in China are troubling.

To stay informed, I read a number of blogs by political activists but also academics investigating the same topics, one of them is Melissa Wall and her blog. She is quite positive and informs us that the future of the alternative and in particular citizen media is promising. However, she also warns us that the fruitful effects of digital activism and the journalistic endeavours of citizen media are optimistic, but there remains the issue of the digital divide and a constant lack of finances to those organizations practicing citizen journalism. Inaccessibility to the web, either due to repressive governments or offline social inequalities is also known as the digital divide. In addition, Mary Joyce firmly underlines that although digital activists and their citizen media are gradually closing this gap by reaching out to those lacking access to the Internet, it remains an obstacle that needs to be overcome (Joyce; 2010; 83).

In an interview for my thesis on digital activism, I also spoke with Global Voices’s global manager Solana Larsen. She confirmed that censorship has only increased with the booming of the Net itself (Larsen; appendix A; 2012). It is a burdening issue in need of global political and governmental action, as some governments like China and Iran enforce censorship unto their citizens. In the case of Global Voices, help is provided when its bloggers are either jailed or face pressing danger in their homelands due to restricted forms of free expression (Preston in NYT; 2011).

A Final Say

Personally I grew up in a country where Internet barely existed. It was in Holland that I embraced the possibilities of the online world. Right now, the Dominican Republic is experiencing a boom in online connectivity. Millions of youngsters are reconnecting with the world inside but also outside of their country. I speak to some of my cousins on a weekly basis and it has altered our relationship. Yet, at the same time, they still experience problems. The Dominican Republic is a prime example of a country where large-scale corruption leads to the limitation of certain freedoms, including the Internet. It is of vital importance then to understand how online communities engage with one another, and especially those fighting for their right to speak freely.

Throughout these masters’ I would like to continue exploring the inner workings of online communities and their practice of mobilisation within their and other blogospheres. Ultimately I would like to make use of this academic year to create a comprehensive analysis on how a variety of individuals and communities apply the newest digital tools and applications to link their information, communicate with one another and thus achieve their goals.

Recommendations

I recommend a visit to the following Unlike Us conference. Even better, if your calendar allows, Pakhuis de Zwijger has a large engagement with new media and local practices of digital culture. Lastly, I try to keep up with Bits of Freedom and their daily tweets and flow of information. And it is always possible to create just another few links to recent writers on this topic like Rebecca MacKinnon. She can be found on Twitter and Facebook and always provides quite valuable information on recent events within the realm of digital activism.

References:

Jenkins, H. 2002. Interactive Audiences?: The ‘Collective Intelligence’ of Media Fans” in Dan Harries (ed.), The New Media Book, (London: British Film Institute, 2002). [Also in Fans, gamers, and bloggers] URL: http://web.mit.edu/cms/People/henry3/collective%20intelligence.html. Last visited 11th of February 2012.

Jenkins, H. Convergence Culture. New York: NYU Press, 2006.

Joyce, Mary. Digital activism decoded: the new mechanics of change. 1st. New York and Amsterdam: International Debate Education Association, 2010. Web. <http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/~sjm217/papers/digiact10all.pdf>.

Kahn, Richard, and Douglas Kellner. “New Media and Internet Activism: From the ‘Battle of Seattle’ to Blogging.” New Media Society. 6.1 (2004): 67-85. Print. <http://nms.sagepub.com/content/6/1/87>.

McKinnon, Rebecca. “Flatter world and thicker walls? Blogs, censorship and civic discourse in China.” Public Choice. 134. (2008): 34-106.

[1] The Arab Spring was a series of revolutions and uprisings throughout the Middle East and North Africa, starting in Tunisia on December 18, 2010. Since the Tunisian revolution, there has been an Egyptian revolution, civil war in Libya, uprisings in Bahrain, Syria and Yemen, major protests in Algeria, Iraq, Oman, Morocco and Jordan, and demonstrations in several other countries. Even Time Magazine announced the year 2011 as the year of the protester (Time Magazine; 2012).