HelpOut: Real Help for Real People

The Crisis at Hand

Political upheaval in the Middle East, Africa and South Asia have forced about 464,000 migrants to cross into Europe in 2015, a phenomenon referred to as the “Refugee Crisis” (Park). Numerous tragic events, like the two boats that sank in the Mediterranean sea, the truck in Austria, and the little boy on the Greek beach sparked strong reactions on social media. Viral photos, touching stories and hashtags were shared across platforms such as Facebook and Twitter. Which leads one to wonder, how many people who have talked about the Refugee Crisis on social media have actually done something about it?

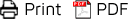

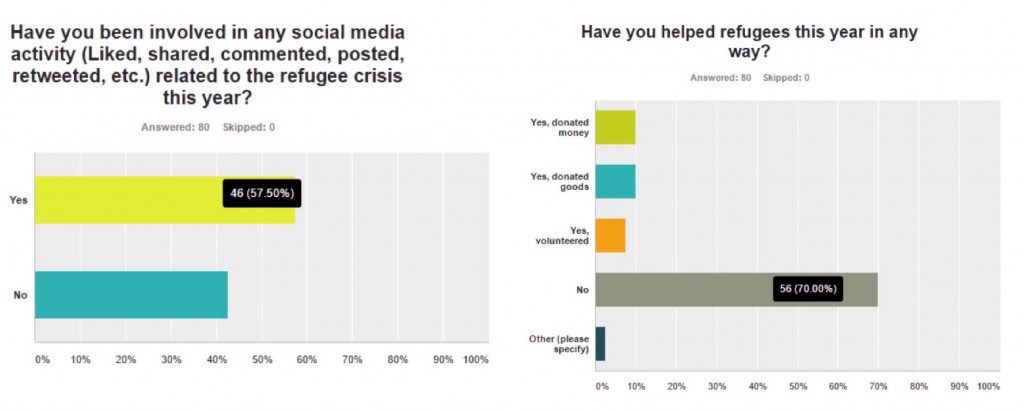

To answer this, team HelpOut conducted a three-question survey with 80 respondents from the EU.

The results show that 57.5% of the respondents talked about the refugee crisis online, but 70% did not help in real life. This connects to the argument about whether people who show support for a cause on social media could feel less obligated to follow through with a meaningful contribution (Schumann and Klein 317; Kristofferson, White and Peloza 1151). Participating on social media can be a comfortable alternative to donating money or volunteering in the name of charity. Hence, social media participation has been criticized as ‘slacktivism’, or a passive contribution that does not wield change.

On another note, the survey results also show that the main reason for not helping out was that they didn’t know how. A simple search query on google.nl will wield results from US, UK and Australia-based agencies. These reflect the difficulty for dutch citizens to reach out because options are not readily available to them.

How HelpOut Works

Hence, the problem is that people want to help but don’t know how. That is why the HelpOut team proposes to create a digital platform which connects ordinary citizens with official institutions, beginning with the Netherlands.

First, the group will find partner non-governmental organizations (NGO’s) that help refugees in the Netherlands.

COA (https://www.coa.nl/en), UNHCR (http://www.unhcr.org), Vluchtelingen Werk (http://www.vluchtelingenwerk.nl/)

By coordinating with these institutions, HelpOut can access a credible database for the platform. These organizations will scan refugee camps for urgent needs and upload these to the official HelpOut website. From there, users can view the lists and select which items they can take to drop off locations across the Netherlands. The partner organization can then collect and distribute them where needed. The platform will also provide channels where users can participate in activities that can enrich refugees’ lives. See how the website looks in this video:

or click through help-out.wix.com/helpout.

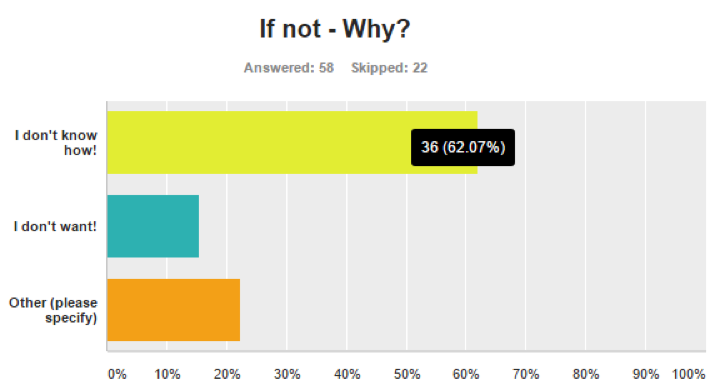

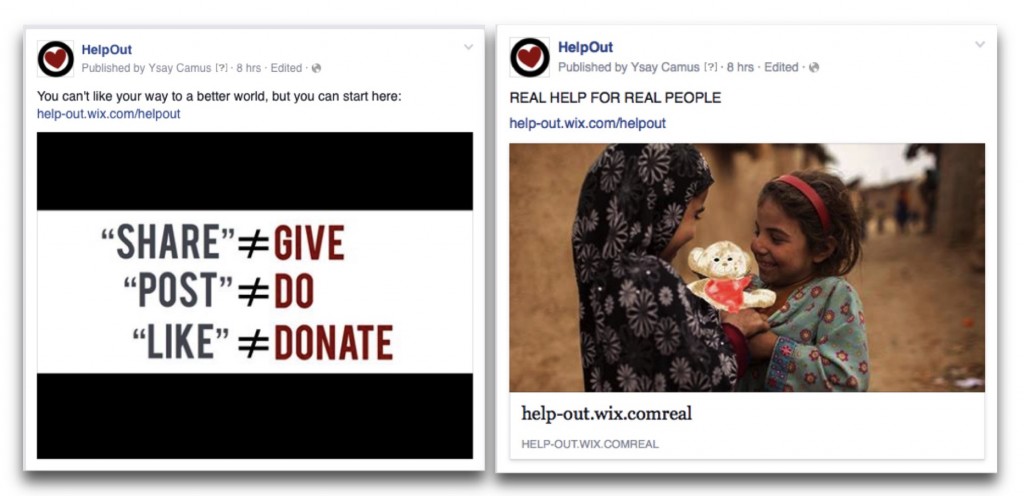

How will HelpOut reach slacktivists and get them to move beyond mere liking, sharing and tweeting? An awareness campaign will be launched across social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Youtube, Instagram, and will be targeted to those who talked about the crisis online. HelpOut will generate clever and catchy content that hit the heart (see sample posts below). The different elements of the campaign will be integrated with one key message, “Real Help for Real People”.

HelpOut also plans to use key influencers, humanitarians or organizations with a large following, to help spread the word. In doing so, HelpOut will act as a major coordinating platform between NGO’s taking care of refugees and Dutch citizens willing to help. In the long run, HelpOut aims to expand and provide aid to any humanitarian crisis happening around the world.

The Surrounding Debates

‘Slacktivism’ versus Helping Out

HelpOut intervenes in the academic debate about the changing nature of activism through social media. On the one hand, it is argued that online participation results in what is called ‘slacktivism’: minor offline engagement with little impact on the situation of the people who need help (Schumann and Klein 310). This behavior is usually motivated by a sense of belonging to a group, rather than personal interests, and it decreases the likelihood of offline engagement such as signing a petition or joining a demonstration (Schumann and Klein 317; Kristofferson, White and Peloza 1151).

On the other hand, it is argued that social media has a strong connective quality, which can help mobilize potential activists (Shirky 29; Fatkin and Lansdown 584). Social media increasingly becomes a tool for coordinating activism (Shirky 30). Although social media users cannot click (or ‘like’) their way to a better world, this does not mean that social media cannot be used effectively (Shirky 38).

This is where HelpOut comes into play. HelpOut aims to connect ordinary citizens to official institutions on a digital platform where users can substantiate meaningful offline impact through their online activity.

The Politics of a Crisis Platform

Creating a digital platform for the refugee crisis may seem like an outright solution. However, it raises political questions from conservative parties and concerned citizens who are afraid of the rising numbers of refugees. The leader of the rightwing Liberty Party (Partij van de Vrijheid), Geert Wilders, dominates the debates about the crisis and refers to the crisis as a “ticking time bomb.” With sharp one-liners like “the government is at the wrong side of history at the moment” and “the survival of our beautiful nation is at risk”, he portrays the fear and discontent of his voters (in the latest polls one sixth of the voting population). This extreme viewpoint is opposed by other parties in Dutch parliament who are willing to take in more refugees. Because of this political impasse it becomes hard for the government to actually help refugees. That is why NGO’s and an online platform like HelpOut have a better chance of succeeding. For more information about the politics of platforms please visit our site.

Why Helping Out Matters

As the growing number of refugees continues to overwhelm government officials and public debates, HelpOut surfaces as an ambitious but well-meaning platform that allows ordinary citizens to be part of the solution.

The debates surrounding it are both academic and public. The academic debate concerns the term ‘slacktivism’ and seeks to answer the question whether social media engagement results in less offline impact for the people who need help. The public debate concerns the political impasse that is currently at hand in the Netherlands. The government has a lot of trouble in dealing with the sentiments and fears that are put forward by concerned citizens and Geert Wilders. Because of this dilemma the help for refugees is currently not sufficient, resulting in the need for a platform like HelpOut.

2015 will go down as the year the “Refugee Crisis” gained momentum. Hopefully, it can also be remembered as the year new media enabled ordinary citizens to treat fellow human beings with compassion.

Reference List:

- Christensen, Henrik Serup. “Political Activities on the Internet: Slacktivism or Political Participation by Other Means?” First Monday 16.2 (2011): n. pag. 16 September. 2015.

- van den Dool, Pim. “Keiharde confrontatie Wilders en Kamer om ‘asieltsunami’.” NRC. 2015. NRC.13 January 2015. <http://www.nrc.nl/nieuws/2015/09/16/live-kamer-bespreekt-kabinetsbeleid- bij-algemene-beschouwingen>.

- Fatkin, Jane-Marie, and Terry C. Lansdown. “Prosocial Media in Action.” Computers in Human Behavior 48 (2015): 581–586.

- Kristofferson, Kirk, Katherine White, and John Peloza. “The Nature of Slacktivism: How the Social Observability of an Initial Act of Token Support Affects Subsequent Prosocial Action.” Journal of Consumer Research 40.6 (2014): 1149–1166.

- Park, Jeanne. “Europe’s Migration Crisis.” Council on Foreign Relations. 2015. Gideon Rose and Jonathan Tepperman. Council on Foreign Relations. 17 September 2015. <http://www.cfr.org/migration/europes-migration-crisis/p32874>.

- Schumann, Sandy, and Olivier Klein. “Substitute or Stepping Stone? Assessing the Impact of Low Threshold Online Collective Actions on Offline Participation: Substitute or Stepping Stone?” European Journal of Social Psychology 45.3 (2015): 308–322.

- Shirky, Clay. “The political power of social media.” Foreign affairs 90.1 (2011): 28-41.