Tagging onto #MeToo

Halleluja!

Alyssa Milano was preaching to the choir with her tweet on october 15th 2017. As a young feminist that has experienced her share of harassment and patriarchal justifications, she could not have found a more receptive public.

But my high on the possibility of gender equality did not necessarily extend to the rest of the world. As male co-workers used the phrase as a joke and female friends commented ‘hysteria,’ the question ‘if a hashtag is even capable of social change?’ occupied my mind.

So this exploration in into the historical context of online feminism, hashtag activism and the challenges of #MeToo is a personal quest. Is there value in tagging onto #MeToo?

#MeToo

While #MeToo has not been the first hashtag addressing sexual harassment, even in 2017, it is certainly the most successful one (Main n.p.).

After Charmed star Rose McGowan was temporarily banned from Twitter as a result of her accusatory tweets at the address of Harvey Weinstein, her co-star Alyssa Milano reacted with this tweet that was retweeted more than 17.000 in the first 24 hours that followed (Connellan n.p.).

A large part of the mainstream media attention goes to allegations of sexual harassment by prominent figures in the entertainment industry, like Weinstein or Kevin Spacey. But the fact that the hashtag was used in 1.2 million tweets by the 19th of October shows, as Alyssa herself said, ‘the magnitude of the problem’ (Lekach n.p.). The pandemic use of the hashtag shows that sexual harassment is not a problem confined to Hollywood. Under #MeToo victims of sexism, sexual harassment and assault have been able to communicate the enormity of the issue (Parham n.p.).

What sets #MeToo apart from the other hashtags addressing sexual harassment is not that it introduced a feminist debate on social media or that it uses a hashtag as an activist tool in the battle against sexism, but the sheer magnitude in which it is being used.

A Framework for Digital Feminist Activism

The Online Opportunities for Feminism

From Twitter, #MeToo spilled over to Instagram and Facebook. This new social media give the opportunity for marginalised voices to speak out. Because participants do not have to venture into a physical public space and can comment anonymously, the risks of speaking about contested issues is reduced (Antonakis-Nashif 104). While at the same time they can find comfort and support in like-minded individuals (Morahan-Martin 686).

Feminists have a conflictual relationship with the dominant discourse, that is mostly of patriarchal nature. They therefore position themselves as a counter public in the space of political action (Drüecke and Zobl 39). Twitter gives feminist a possibility they would have never had offline: it connects them to a global audience, with short messages that are published without any intervention from an editing party (Morahan-Martin 684). This way they can insert their thoughts in the general public discourse.

These possibilities increases the opportunity of feminists activist to have their voices heard (Stache 162).

The Hashtag

The hashtag is a tool in itself. It connects tweets that are related to an individual subject thereby creating a public for that issue. In turn, users can add to the topic by incorporating the hashtag in their message (Burns and Burgess 15-17). This gives the possibility to individuals that feel marginalised to not only share their story, but to include themselves in a movement around the subject. (Antonakis-Nashif 101)

Historical Hashtags

Over the years multiple attempts have been made to raise awareness about sexism through hashtags. In 2012 The Everyday Sexism Projects instigated #shoutingback and #EverydaySexism, which were internationally used (Drüecke and Zobl 36). #YesAllWomen surfaced more spontaneous after the Elliot Roger shooting in 2014 and culminated 61,500 tweets in two days After Donald Trump’s “pussy grabbing” incident the hashtag #NotOkay entered the arena and stories about harassment and assault were shared with this tag. However, after he was elected president this initiative died quietly (Main n.p.).

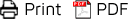

#Aufschrei

Notably in this regard is also the hashtag #aufschrei. The hashtag was introduced by young feminist Anne Wizorek in the night of 23-26 January 2013. Like Milano’s #MeToo, she aimed to gather experiences with sexism to highlight the problem (Antonakis-Nashif 104). Here efforts had effect. Concretely, the attention for the issue created a greater demand for anti-discrimination facilities and services were diversified (Antonakis-Nashif 111). Her hashtag focussed attention on a topic that was previously marginalised, mobilised the issue and made it part of the general public debate (Drüecke and Zobl 48-50).

Challenges to #MeToo

Cultural differences

Within five days #MeToo measured 1.7 million tweets originating from over 85 countries in the Middle East, Europe, Asia and the America’s (Lekach n.p.). The widespread not only shows that sexual harassment is a worldwide issue, it has also created a global movement on the subject. Within this digital community physical boundaries fade and all nationalities, provide they have access to internet, can participate in the political debate (Carter Olson 780).

However, the universal use of a hashtag often disregards the cultural specifics that can impact an issue. Especially for women in developing countries, the possibility for equal rights and the existence of sexism are related to the prosperity of the country, culture and religion. So for activism to have an impact, it needs to be tailored to the local situation (Carter Olson 780).

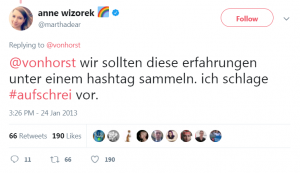

This issue is illustrated by Turkish journalist Kübra Gümüsay, after the upsurge of #Aufschrei. She felt disconnected from the main movement as in here experience sexism was always combined with racism. To that end she launched the hashtag #Schauhin, meaning ‘look closely’ (Antonakis-Nashif 105)

Hashtag Hazards

Especially, feminists of colour have used social media to draw focus to the relation between sexism and racism (Antonakis-Nashif 103). In this tradition, activist Tarana Burke started the “Me Too” campaign on MySpace as a way for young women of colour to speak up about abuse (Schwartz n.p.). Last October, nearly ten years later, Milano refashioned the phrase as an hashtag to represent all stories of sexual abuse. Although it cannot be denied that this created a surge in the attention to sexism, for the original target, women of colour, it does not have the same meaning.

The uncoordinated existence of hashtags can hurt a movement in two distinct ways. On the one hand, several hashtags about an issue can come into existence and compete for the same public. Thereby it hinders the development of one unified movement (Burns and Burgess 18). On the other hand it is not uncommon that the same hashtag serves multiple purposes (Stache 163). While the popular use of #MeToo remained close to its original meaning, the hashtag can be hijacked to diminish its influence over an issue. Ridicule, victim blaming and victimising can create a situation where the issue is taken less serious (Antonakis-Nashif 106).

The expense of going viral

The flood of messages with the hashtag #MeToo illustrate a moral outrage. With the increasing number of posts, the possibility for societal change can decline. The exorbitant use exhausts the meaning behind the hashtag. The safety of commenting on social media, makes it easy to participate and therefore the nuances between slightly disagreeing and being totally outraged disappear. In addition, online participation could result in less offline actions like donations or volunteering, having already fulfilled the social duty online, for all to see (Crockett 771).

Patriarchy

Some men are more critical of the #MeToo movement. Tweets like “Where is the line? Can’t I longingly stare down someone’s blouse” or “Do I have to apologise for having balls?” appeared on Dutch accounts (Verlouw n.p.). Words that excuse sexist behaviour as ‘manly.’ This is to bad as the contribution of men to the movement could really increase its social impact. Men who speak up against sexism are perceived as more legitimate than the women, because they do not benefit for the action themselves (Drury and Kaiser 643). New hashtags like #Ihave, #HimThough and #HowIWillChange, actually do give men the opportunity to involve themselves in the issue.

Tagging on

My idealistic enthusiasm after the initial #MeToo tweet has met the more uncertain reality of hashtag activism. While a viral hashtag does not ensure change, awareness can help progress. So consider me tagged on too #MeToo.

The social impact of a movement like #MeToo is hard to measure, especially in this early stage. Past initiatives have shown that a hashtag addressing sexism can enhance awareness and stimulate the formation of a online community or movement. #Aufschrei even inspired societal changes.

The #MeToo movement faces several challenges. Among those are medium specific challenges like the ambiguity of a hastags and the drawbacks of a viral message. Other concern the cultural diversity of the public and the more traditional criticism on issues concerning sexual harassment.

#MeToo did provoke a debate on the issue in the European Commission (Schreuer n.p.), but no structural changes have been made in the aftermath of the viral hashtag. Right now its main accomplishment is making sexual harassment part of the mainstream public debate. However, it is one thing to talk about sexual harassment and a whole other thing to make significant impact (Stache 163).

References

Antonakis-Nashif, Anna. “Hashtagging the Invisible: Bringing Private Experiences into Public Debate: An #outcry against Sexism in Germany.” Eds. Nathan Rambukkana. #Hashtag Publics: The Power and Politics of Discursive Networks. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2015. 101-115.

Bruns, Axel and Jean Brugess. “Twitter Hashtags from Ad Hoc to Calculated Publics” Eds. Nathan Rambukkana. #Hashtag Publics: The Power and Politics of Discursive Networks. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2015. 13-19.

Carter Olson, Candi. “#BringBackOurGirls:digital communities supporting real-world change and influencing mainstream media agenda’s.” Feminist Media Studies 16 ( 2016): 772-787.

Connellan, Shannon. “#MeToo: Hashtag shared by Alyssa Milano encourages personal stories of sexual harassment.” Mashable. October 16, 2017. Accessed 15th November 2017. http://mashable.com/2017/10/15/me-too-alyssa-milano-twitter-harassment/#PONkcsbx9SqD

Crockett, M.J. “Moral outrage in the digital age” Nature Human Behaviour 1 (2017): 769-771.

Drüecke, Ricarda and Elke Zobl. “Online feminist protest against sexism: the German-language hashtag #aufschrei.” Feminist Media Studies 16 (2016): 35-54

Drury, Benjamin J. and Cheryl R. Kaiser. “Allies against Sexism: The Role of Men in Confronting Sexism.” Journal of Social Issues 4 (2014): 637-652.

Lekach, Sasha. “#MeToo hashtag spreads beyond the U.S. to the rest of the globe.” Mashable. October 20, 2017. Accessed 15th November 2017. http://mashable.com/2017/10/19/me-too-global-spread/#TI1YSlU.GmqI

Main, Allison. “The #MeToo hashtag was used in an enormous number of tweets.” Mashable. October 17, 2017. Accessed 15th November 2017. http://mashable.com/2017/10/16/me-too-hashtag-popularity/#zWfpahBL9iqn

Morahan-Martin, Janet. “Women and the Internet: Promise and Perils.” CyberPsychology & Behaviour 3 (2000): 683-691.

Parham, Jason. “After Harvey Weinistein, It’s Time To Ask: Can the System Change?” Wired. November 11, 2017. Accessed 15th November 2017. https://www.wired.com/story/harvey-weinstein-system-change/

Schreuer, Milan. “A #MeToo Moment for the European Parliament.” The New York Times. October 25, 2017. Accessed 15th November 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/25/world/europe/european-parliament-weinstein-harassment.html?_r=0

Schwartz, Alexandra. “#MeToo, #ItWasME, And The Post-Weinstein Megaphone of Social Media.” The New Yorker. October 19, 2017. Accessed 15th November 2017. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/metoo-itwasme-and-the-post-weinstein-megaphone-of-social-media

Stache, Lara C. “Advocacy and Political Potential at the Convergence of Hashtag Activism and Commerce.” Feminist Media Studies 15 (2015): 162-164.

Verlouw, Charlotte. “Na #metoo colgt nu #Ihave: Ook ik ben schuldig aan seksueel geweld.” Trouw. October 19, 2017. Accessed 15th November 2017. https://www.trouw.nl/samenleving/na-metoo-volgt-nu-ihave-ook-ik-ben-schuldig-aan-seksueel-geweld~a75d35b9/