Data Choreography

Information visualization field is lately becoming more and more manisfested in the physical space; in some cases as an everyday life practice and more often in the form of an ambient object .

We can observe projects in which data about casualties in Iraq is visualized in a tatoo made on a man’s back, which shows the relations between locations, deaths and military operations; energy consumption data is displayed collectively by illuminating the inside of apartments in a community building with lights in diferent colors, depending on the level of consumption; or a global warming awareness campaign in China that is realized by representing CO2 emissions from street traffic, with a big black “sphere of pollution” that is coming out from a real car’s exhaustion pipe.

In the design field, ambient devices can show data about energy consumption at home. These objects that are increasingly becoming part of our home furniture are useful and sophisticated “behavior advisers” for saving energy. In parallel, wearable data devices are commonly used by people as a way to communicate their personal information with others or to inform them about, for instance, the environmental noise level. By wearing this kind of clothes or jewelry, data can be visualized with commercial purposes (by companies) or with technological goals (by research labs). In any case, ‘performing’ information visualization can be a persuasive tool and can contribute to making people aware about different issues, as Andrew Vande Moere explained in his last lecture at the SEE Conference last April (2010). Researchers, artists, activists and educators who work with software programs for turning numbers (data) into images are also interested in making these images more effective by turning them into physical objects or performances. Persuasive visualization’s main goal is to make data visible and present.

It seems clear by following these examples that the “performative turn” has left traces in the Infovis field as well, and that the ubiquitous computing is becoming integrated in new ways within the realm of information. Data presented in this way blurs the boundaries between disciplines (architecture, data art, Infovis, locative media, geography, etc) and interests (commercial and academic). In this context, it is difficult to distinguish a proper information visualization project related to the performative field.

Dance, for example, has always been one the artistic disciplines that have made use of data to recreate and suggest new ways in which the audience can perceive and experience body movement and the space [1]. The goal of using data visualization with dance is not exactly the same as in the performative Infovis examples above. In dance, the visualization of the performance has always been related to the realm of human computer interaction in oder to create a sense of closeness between dancers and the audience. Gideon Obarzanek has worked on visualizations with interactive software and dancing movements. Based on aesthetic and kinesthetic stimulus, his work with the Chunky Move dance company offers visualizations distributed into different layers of images and movements that “we cannot normally see but which we feel or know to exist”. This can be perceived as an aesthetic way to understand the dancer’s movement and appreciate it much more. It is a sensitive way to complement the dance with visualizations based on data, which in several ways works also as a feedback tool.

However, what about the other way around?. Can we understand the movements of a dancing performance by not focusing only on the aesthetic experience? What if our interest is about the movement itself and the rules which compose choreography? We cannot perceive every movement in space in a choreographic performance. But, could we understand the process of choreography? Is it possible for us to understand dance in a scientific way? How can Infovis help us to understand relational movement in space?

I propose in the following brief overview, to explore the connections between choreography of movements and information visualization, within an educational research context, through a project that visualizes choreographic information in new ways, Synchronous Objects.

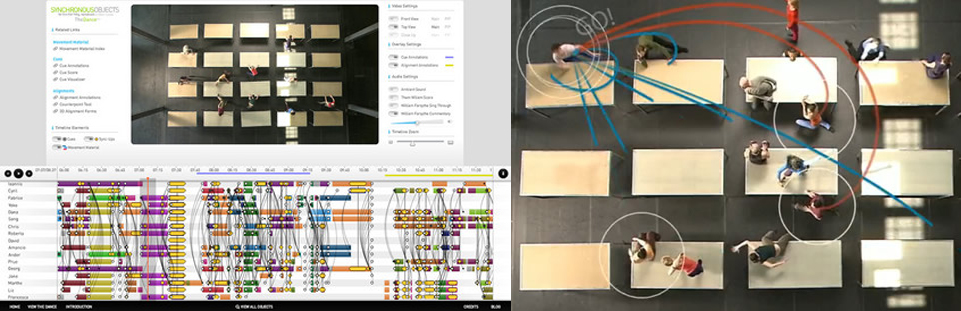

This project is seeking to make dance accessible through visual communication techniques. It flows from dance, to data, to objects. Through visualizations in form of information graphics, 2D and 3D animations and visual dance scores, an interdisciplinary team (choreographer William Forsythe, Ohio State University’s Advanced Computing Center for the Arts and Design (ACCAD) and the Department of Dance, Synchronous Objects) has develop a set of data visualization tools that can capture, analyze and present the choreographic structures and components of Forsythe’s “One Flat Thing, reproduced” (OFTr), which premiered in 2000. After 3-year collaboration, the project has involved a group of over 30 artists, dancers, designers and scientists who explain here their interdisciplinary research.

This project is seeking to make dance accessible through visual communication techniques. It flows from dance, to data, to objects. Through visualizations in form of information graphics, 2D and 3D animations and visual dance scores, an interdisciplinary team (choreographer William Forsythe, Ohio State University’s Advanced Computing Center for the Arts and Design (ACCAD) and the Department of Dance, Synchronous Objects) has develop a set of data visualization tools that can capture, analyze and present the choreographic structures and components of Forsythe’s “One Flat Thing, reproduced” (OFTr), which premiered in 2000. After 3-year collaboration, the project has involved a group of over 30 artists, dancers, designers and scientists who explain here their interdisciplinary research.

The dance piece is based on the idea of expressing and transforming the choreographic ideas behind William Forsythe’s dance [2] explained through 20 visual objects, over 40 movies and 5 generative tools. The interesting thing is that the academic aim of this project is to make dance and movement understandable by using visualizations techniques; movement densities, annotations, generative tools and algorithms are used with this purpose. Forsythe says about the collaboration that his approach is to put things into question, like: “What else might this dance look like?” and “What else, besides the body, might physical thinking look like?. Specifically, the project explains how the Forsythe’s “counterpoint” concept is performed by dancers. Movement material, cueing and alignment are the three systems that interact in form of themes (understood as dancing movements). There are 25 themes which are recombined over the dance and also improvise movements that dancer can do “by translating specific properties of other’s performer’s motion into their own”.

Their data includes Spatial Data, tracking a single point of each dancer in three-dimensional space, and Attribute Data, “built from the dancers’ first hand accounts, such as when the gave or received a cue, what alignments they followed, when they were improvising and what themes they were performing in every second of the dance”. Forsythe’s dance is much related to time. To him, “bodies in dance are time machines, time is the exquisite product of dancing body” [3]. Erin Manning writes; “In Forsythe’s work, time-machines often stand-in as propositions for generating movement. Using both quantitative methods (clocks, watches, metronomes) and qualitative devices (varying the volume and melody of a voice while counting, altering the duration and rhythms of the counts), Forsythe plays with the double time of movement”. [4]

Their data includes Spatial Data, tracking a single point of each dancer in three-dimensional space, and Attribute Data, “built from the dancers’ first hand accounts, such as when the gave or received a cue, what alignments they followed, when they were improvising and what themes they were performing in every second of the dance”. Forsythe’s dance is much related to time. To him, “bodies in dance are time machines, time is the exquisite product of dancing body” [3]. Erin Manning writes; “In Forsythe’s work, time-machines often stand-in as propositions for generating movement. Using both quantitative methods (clocks, watches, metronomes) and qualitative devices (varying the volume and melody of a voice while counting, altering the duration and rhythms of the counts), Forsythe plays with the double time of movement”. [4]

To Forsythe, choreography and dance are two very different practices; “in the case that choreography and dance coincide, choreography often serves as a channel for the desire to dance. One could easily assume that the substance of choreographic thought resided exclusively in the body. But is it possible for choreography to generate autonomous expressions of its principles, a choreographic object, without the body?”.[5].

Media technologies do not look for complementing the artistic performance or tracking the dancer’s body movements. Instead, both, dance as an artistic experience and the body, are relegated and it is the concept of choreography which is highlighted in order to get further insights. Their purpose is to reflect a challenge of “making dance knowledge explicit and sharing it not only on stage and in the studio (as we are accustomed) but also through media objects”[6]. This is perfectly reflected on the project team’s comments at their website, where it can be understood that in this case is not the art field that uses visualization techniques to improve their performance, but the dancing performance itself is deconstructed through visualization techniques. The goal is to offer users a better understanding of the movement executed. Thus, user is anybody who “doesn’t understand dance” and wants to play with synchronous objects visualization. The project provides a good understanding of what information visualization and art, in the context of interdisciplinary research, is all about.

[1] Manning, Erin Prosthetics Making Sense: Dancing the Technogenetic Body. Fibreculture Journal Issue 9. 2006 http://journal.fibreculture.org/issue9/issue9_manning.html

[2] Forsythe’s choreography is grounded in a deconstructive reconsideration of the possibilities of classical ballet structures and theatricality, innovative applications of improvisation which he and his ensemble have developed and refined in over two decades of sustained dance research, and an increasingly collaborative approach to producing choreography. Forsythe works engage deeply with performative conventions and the fields of contemporary visual arts, architecture, and interactive multimedia. In 1994, Forsythe authored a pioneering and award-winning computer application Improvisation Technologies: A Tool for the Analytical Dance Eye which is used by professional companies, dance conservatories, universities, postgraduate architecture programs and secondary schools.

At http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Forsythe_%28dancer%29

[3] Forsythe, William. Suspense, ed. Markus Weisbeck (Zurich: Ursula Blickle Foundation, 2008).

[4] Manning, Erin. Propositions for the Verge. William Forsythe’s Choreographic Objects Inflexions magazine, January 09.

[5] Forsythe, William. Choreographic Objects, 2009 at http://www.wexarts.org/ex/forsythe/

[6] Zuniga, Norah at http://mediacommons.futureofthebook.org/imr/2010/04/28/synchronous-objects-what-else-besides-body-might-physical-thinking-look