Iranian Censorship of Women’s Online Magazines

The report below was generated as part of an assignment for the University of Amsterdam’s Digital Methods course – November 2010.

Censorship of Women’s Online Consumer Lifestyle Magazines in Iran

Although media censorship in Iran is a widely publicized fact, this research report seeks to establish a clearer picture of which women’s online consumer lifestyle titles Iranian web users are currently forbidden to view. This report was conducted using the University of Amsterdam Media Studies Department’s tool called Censorship Explorer. This tool allows users to input URLs and test them against known proxy servers around the world. For this research all available Iranian proxy servers listed in this tool were used although the number varied over the three days of testing in November 2010. The list of nineteen women’s consumer magazine URLs was compiled using Google.com as well as lists from international publishing houses and the researcher’s existing knowledge of the consumer lifestyle magazine market.

Censorship by the Iranian Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance has been previously assessed by both Reporters Without Borders and the OpenNet Initiative (ONI), which have labeled it as “repressive” and “pervasive” respectively. According to the ONI, internet usage in Iran is one of the fastest growing in the region, yet in 2008 and 2009 the organization confirmed Iran as one of the most “extensive filterers of the internet” in the world. On their website, opennet.net, the ONI singled out a more focused effort on the part of the Iranian government to block women’s rights organization online.

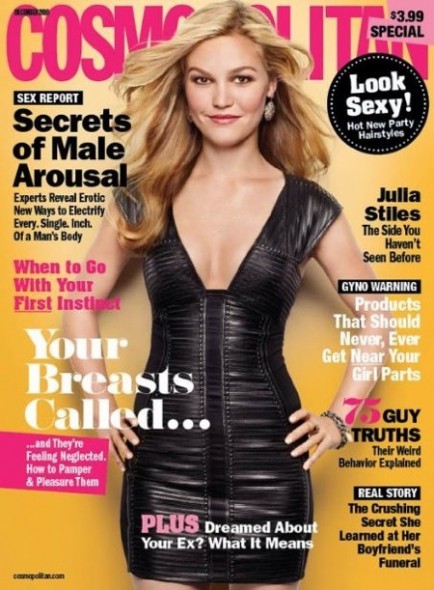

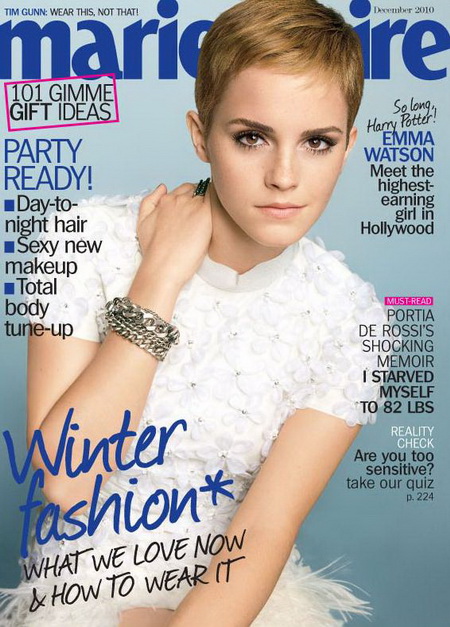

According to the Iranian Constitution, “publications and news media shall enjoy freedom of expression provided that what they publish does not violate Islamic principles or the Civil Code” (“Status of the Internet in Iran” 7). Women’s online consumer lifestyle titles are seen as anti-Islamic due to their immoral content; this often refers to content of a sexual nature (“Status of the Internet in Iran” 12) or according to the ONI, “images of women in provocative attire”. However, women’s magazines form a critical and vibrant component of the online content landscape with many titles contributing editorial coverage to the women’s movement. Often, their editorial covers human rights issues, women’s health as well as relationship issues and trends in society. A magazine title such as Marie Claire (currently forbidden by at least one Iranian proxy server) regularly runs features entitled “World Report” which highlights women’s rights issues and “grittier” news features which can be viewed as critical of the Iranian government’s rule of law.

This paper seeks to list the forbidden women’s lifestyle titles to support the ONI’s finding that censorship targets the women’s rights movement.

METHOD:

URL collection

The sample consists of URLs collected using the librarian or editor’s approach. These URLS include nineteen of the biggest-selling and best-known magazine titles in the world that appeal to women. These were compiled using Google.com as well as lists from major publishing houses such as Hearst.com and were informed by the researcher’s existing knowledge as a former magazine publisher.

The list includes fashion magazines (Vogue.com; Cosmopolitan.com; Glamour.com; Harperbazaar.com; Elle.com;Instyle.com); gossip and celebrity magazines (People.com; Heatworld.co.uk;USweekly.com); one teenage magazine (seventeen.com);one health and fitness magazine (Womenshealthmag.com); a few general interest titles (Nationalgeographic.com; Economist.com; Monocle.com;Time.com;Vanityfair.com); one consumer/housekeeping magazine (Goodhousekeeping.com) and a women’s adult magazine (Playgirl.com).

This sample of URLs does not represent a complete list of all available online titles in the women’s market. The selection was based on the popularity of the titles (available globally with a large readership) and the title’s ability to create diversity in the sample. For example Goodhousekeeping.com, as the name suggests is about housekeeping (and consumer) techniques and can be seen as a title that will not easily be selected for censorship, thus providing a contrast to the other titles in the sample such as Cosmopolitan.com which often runs editorial of a sexual nature. The addition of a title such a Playgirl.com was to represent the extreme of the scale (overtly sexual content) to establish that this is in fact censored. The other titles in between the two extremes of Goodhousekeeping.com and Playgirl.com are not easily identifiable as candidates for censorship and thus needed to be tested and categorized.

Tools

The individual URLs from the sample were inputted into the Censorship Explorer tool. All available Iranian proxy servers were selected to test against the URLs inputted to establish if the sites were forbidden (403) or OK (200). The results were then randomly screen captured and then all listed in an Excel worksheet.

Proxies

The proxies that were available to test via the Censorship Explorer tool are listed below:

1.) 217.146.208.70:8080: this proxy was tested on the 9 November 2010 and showed results of two kinds: “403 Forbidden” sites and “200 OK”. However, on the subsequent two days (10 and 11 November 2010) this server showed “connection failed” when results were displayed.

2.) 212.50.238.101:8080: this proxy server was tested on the 9 November 2010 and showed “connection failed” as the only result for all URLs tested. On the subsequent two days (10 and 11 November 2010) this proxy returned no results yielding a blank space.

3.) 78.39.99.34:3128: This proxy server appeared on the list on the 11 November 2010 and showed a combination of only two types of results: “405 Method Not Allowed” and a blank result.

4.) 85.185.102.241:8080: This proxy became available in the latter half of 11 November 2010 and yielded two types of results: “200 OK” and “403 Forbidden”.

Timeline

The URLs were inputted into the Censorship Explorer tool over a period of three days beginning on the 9 November 2010 and ending on the 11 November 2010. It is important to note that the proxy server list is not static, thus fluctuating between two and four proxies over the testing time period.

Reliability

One major concern with the proxy servers used in this research was the variances in results shown over a three-day testing period. URLs that yielded a “403 Forbidden” result on the first day of testing (9 Nov 2010) showed a “Connection Failed” response on subsequent days (10, 11 Nov 2010). Therefore, instances of “403 Forbidden” results were not replicated to re-confirm findings although newer proxy servers introduced over the testing period yielded a “403 Forbidden” result on those same sites. Evidence of censorship was clearly found, however, this was not captured more than once using the same proxy address.

RESULTS

Of the 19 magazine URLs tested, six titles were listed as “403 Forbidden” indicating censorship of these sites. These sites were:

1. playgirl.com

(Forbidden by proxy 1 on 9 Nov 2010)

2. cosmopolitan.com

(Forbidden by proxy 1 on the 9 Nov and by proxy 4 on the 11 Nov)

3. marieclaire.com

(Forbidden by proxy 1 on 9 Nov 2010)

4. glamour.com

(Forbidden by proxy 1 on the 9 Nov and by proxy 4 on the 11 Nov)

5. harpersbazaar.com

(Forbidden by proxy 1 on 9 Nov 2010)

6. vanityfair.com

(Forbidden by proxy 1 on the 9 Nov and by proxy 4 on the 11 Nov)

The sites that were not censored, yielding a “200 OK” status, included:

1. vogue.com

2. goodhousekeeping.com

3. womenshealthmag.com

4. elle.com

5. monocle.com

6. heatworld.com

7. economist.com

8. nationalgeographic.com

The following sites yielded either a blank result box or a “405 Method Not Allowed” or “504 DNS Name Not Found” or no result:

1. seventeen.com

2. instyle.com

3. time.com

4. people.com

5. usweekly.com

Six sites were censored by at least one proxy server; eight sites were OK and five sites yielded unresolved results.

In analyzing the “403 Forbidden” sites listed above versus the sites listed as “200 OK”, it is important to note the apparent inconsistencies in the censorship (or possible omission of some sites for censorship) by the Iranian authorities. For example, Womenshealthmag.com features women in scantily clad gym outfits throughout the site. It also dedicates much of its online real estate to discussing sexual health. Both of these content genres would be considered immoral content by the authorities for Iranian users, yet it remains uncensored. In contrast, a site like Harpersbazaar.com dedicates the majority of its editorial coverage to fashion news and trends. Although this site may contravene the rules of modesty in the Islamic faith, it is sharply contrasted to images of near-naked gym experts on the Womenshealthmag.com site which is not censored. Although print magazines like The Economist have been subjected to censorship in the past , the online version of this title, as found in this research was not blocked by Iranian proxy servers over the testing period.

DISCUSSION

The results in this report clearly indicate six out of nineteen instances of censorship in the women’s online consumer magazine market in Iran. Although the criteria on which this censorship is based is almost impossible to decipher. If it were on the basis of provocative imagery then many more of the women’s fashion magazine sites would also be censored. If it was on the basis of political comment (critical of the Iranian government) then we might have expected a site like Economist.com (which often highlights Iranian politics) to be censored too. Perhaps this site owner has been more aggressive in voicing its disapproval of the censorship. Perhaps the publisher of sites like Marieclaire.com, which covers global women’s rights issues, should be more vocal about this censorship in Iran.

Despite much of the content of a site like Cosmopolitan.com dedicated to sexual health and performance there is a component of the editorial dedicated to issues of physical and financial wellbeing. It also showcases and celebrates women doing extraordinary work in their fields and can be seen an inspirational content for women across various cultural backgrounds. This type of content, present in many of the censored titles listed in the RESULTS section of this paper can be seen as part of a broader issue of women’s rights. Following on from the ONI’s finding that the Iranian authorities target women’s rights sites this censorship research can be seen as a supportive finding.