The virtuality debate

Media mention the term frequently: virtual. Think of virtual worlds (Second Life), gaming environments (World of Warcraft) or simply social network sites (Facebook). Those are places that don’t exist in a physical, touchable form, except from the hosting servers. But how virtual are those virtual places?

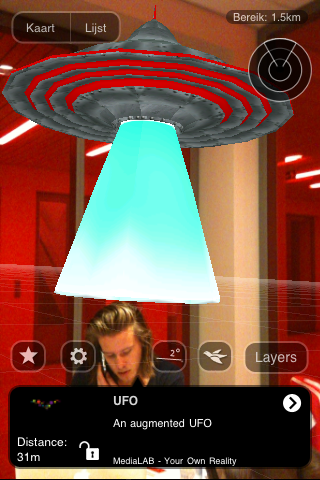

I came up with this question while writing my BA thesis on an augmented reality topic. Augmented reality opens the possibility to add an additional information layer to the reality, with intervention of some device. Do you remember the Terminator, shooting on a police force and counting the human victims afterwards? An additional information layer in his point of view tells the audience the number of human kills: 0. You can view the scene on YouTube, embedding this video has been disabled.

Despite of the Terminator’s futuristic looking view, this idea is becoming reality, especially through the popularization of smart phones. At the time this film was produced, 1991, theories about virtuality were hardly not about the combination of the real and the virtual. Terms like cyberspace and virtual reality indicated a huge gap between the online and offline worlds. Scientists discussed about the rise of virtual places, e.g. Rheingold (virtual communities, 1994), Negroponte (being digital, 1995), Turkle (virtual identities, 1995) and Lévy (virtual reality, 1998).

The emergence of broadband internet, and mobile internet in a later stadium, changed a lot in the meaning of the virtual. Users were constantly connected to the internet and computer mediated communication (CMC) became more established. Nowadays the usage of digital tools is part of the offline world, since users are able to produce and share content everywhere. After the dotcom crash in the early 2000s, virtual worlds are more understood in a broader sociological context.

Steve Woolgar concludes in his 2002 publication Virtual Society? that virtual worlds are not independent, stand alone places, but depends on the user’s physical environment. It’s more like an enrichment of the offline ways of communicating. Think for example of people asking if you received their e-mail, possibly to avoid an endless textual conversation but to make a clear point in the first place. Daniel Miller and Don Slater consider the internet as an ethnographic place instead of a medium that creates places separate from the offline, social life.

In that context, the virtual worlds as mentioned above are highly connected to the offline world. Even though we can discuss about the real impact of Second Life, it is clear that big multinational companies invested lots of money to represent themselves in the online world. Playing World of Warcraft can make you some real money. People use Facebook to announce real events. But still, Facebook is not a physical place.

Perhaps augmented reality is the most obvious appearance of the online/offline combination. While walking in the real space, you are connected to a database which provides you additional info about your physical location. In terms of Michel Foucault we would call these interlinked spaces a heterotopia: a physical existing space containing an extra layer of meanings, the same idea as when you look into the mirror: you see the reflection in a space that does not exist. Augmented reality objects are represented on a physical location, but are actually not there.

Putting this all together, can we still mention the term virtual, or should we redefine our notion of virtuality as a space that can aslo be part of the real world?