Tweeting politics – preaching to the choir?

In May 2012, the French chose Francois Hollande, the Socialist Party candidate, to replace Nicolas Sarkozy as president. François Mitterand lost power in 1995, and since then the government majority had been right wing. After his defeat, Nicolas Sarkozy decided to quit politics, leaving his party (UMP; Union pour un Mouvement Populaire) without a leader.The generation of politicians currently in power have by and large never been in opposition. In addition to a new position and its challenges for both sides (e.g. for the right wing how to regain the power rather than keeping it), the political parties are faced with new technologies and media. Many politicians make a point of maintaining online visibility.

Since US president Barack Obama’s first election in 2008, social media have been broadly used and discussed politically, even if we lack hard and undisputed knowledge of what effect this has on people. It goes without saying that quite a lot of French politicians have started using both Facebook and Twitter. Some, like Nathalie Kosciusko-Morizet (@n_km) and Cécile Duflot (@CecileDuflot), are quite well known and respected for their measured, conscious, and accurate use of the media. Others have been accumulating mistakes (including ones as big as “DM fails”; the action of sending a message to all followers publicly instead of sending it privately to one user), and were eventually turned to ridicule by the Twitter community.

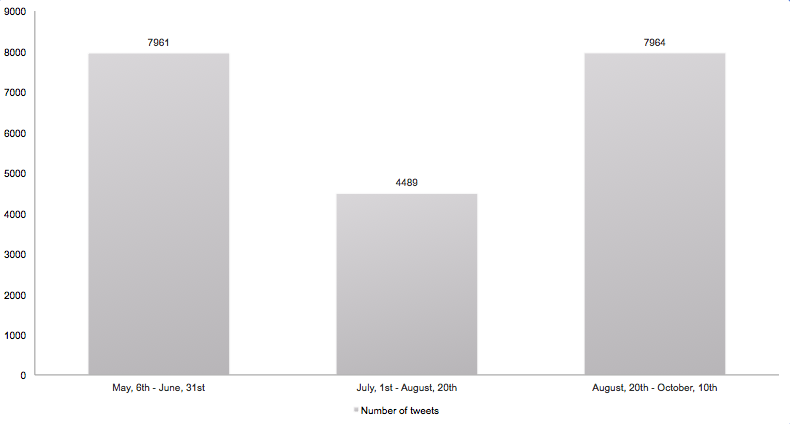

This blog post is seeking to decipher how politicians use Twitter, and what they write about. To what extend do their conversations and posts match with their political discourse? Are right wing traditional topics appearing in right wing politicians’ tweets? Ultimately, this blog post is written to find out what politicians think is a compelling incitement for people to vote from them – and whether it is possible to use Twitter for these means. In order to do so, I selected 30 active twitter users, most from the right wing UMP party, but also users from more radical right wing parties. They all mention their role or activism in their twitter biography, thereby allowing us to perceive their use of Twitter in relation to their public function. Thanks to Twitonomy, I was able to gather all their tweets written between May 6th 2012, the day of François Hollande’s election, and October 10th. These periods are divided in three in order to be able to compare statements in time.

Before expounding further on this dissection, the graph above shows that most Twitter users slowed down their activity during summer. There are few notable differences between the May-and-June period and the September-and-October period, despite the result of the second round of the presidential elections and the two rounds of legislative elections in June. It can mean that Twitter is not considered by these politicians merely as a tool to use only during campaigns, but something to be used everyday. In a way, these figures give proof of a basic understanding of the platform. (But it is still important not to forget that these people are in a permanent position of representation.)

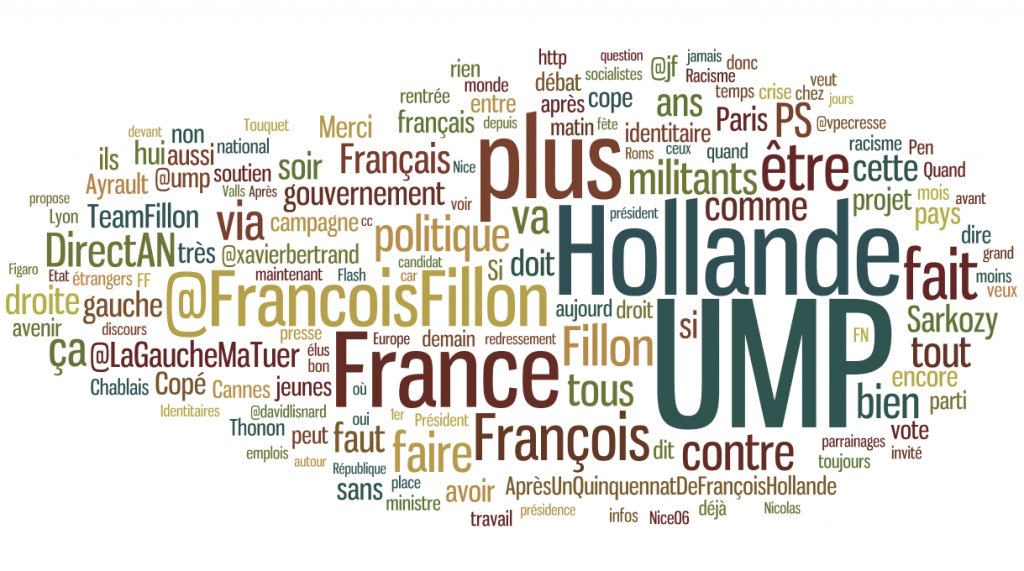

The tag clouds presented here are made from the panels’ tweets. The first word cloud, whose period embrace the presidential election day and both rounds of the legislative elections, display “UMP” – the abbreviation of Union pour un Mouvement Populaire – as the word most used by the examined users. Keep in mind that this is not only used in the tweets themselves, but also as a hashtag. The FN party (Front National, whose orientation is far right wing) is also well represented, with the words “FN”, “Marine” (the name of the leader) and “Pen” (her surname). The right wing parties UMP and FN evoked a collaboration during the second round of the legislative elections. Hollande, the newly elected French president, is represented with the same importance in this cloud as the “PS” (the Socialist Party) which he represents, whereas former president Sarkozy is not very prominent.

During the summer, “UMP” remains the main concern. The city of Cannes makes an apparition – the UMP had already been present with their “caravane” (field campaign) there for some time. While the party was looking for a new leader, the name “Sarkozy” was getting bigger. “Fillion”, the name of a candidate to the presidency of the UMP, appears. Hollande was still well represented, whereas the far right wing-party FN and their leader Marine Le Pen were disappearing from view.

“UMP” and “Hollande” were still the most used words, but François Fillon’s tag was becoming increasingly present. His rival’s name, Jean-François Copé, also made an appearance. Sarkozy’s tag had by this time become quite small, and Marine Le Pen and her party disappeared from the cloud all together. “France” is an important word on all of the three clouds, as discussed later.

All of the demonstrated trends can be seen on the chart presented below. There are three distinct trends concerning the use of tags: “Hollande” and “UMP” bounced after a period of increased use, and can now be found at the same level as before the summer. The summer has was not good for tags “Marine Le Pen” and “FN”, while the frequency of “Copé” and “Fillon” increased.

Trends and clouds tell us one thing: our panel of users use Twitter for self promotion. The Front National and Marine Le Pen were part of the UMP actuality in May and June, and for the second round of the presidential elections, Nicolas Sarkozy could expect some extreme right wing supporters to vote for him. During the legislative elections’ last round, alliances were evoked. Then the parties parted ways, resulting in the UMP taking the FN out of its talks and actuality.

The word “France” appears in quite big in all the word clouds. One could argue that France is traditionally leaning towards having right wing conservative values. But Pascal Marchand shows in this chart that the word “France” appears with a high frequency in several politicians’ speeches, whatever their political affiliation might be.

What, then, relates these tweets to todays’ political discourse? It is hard to say. There is next to no mention of the crisis in the European Union or of any traditional right wing topics (like security and immigration), nor of broader political topics (like economics).

The feeds of the users hereby examined do not intrinsically relay political messages that would bring anything to the debate, but are in a large scale showing either auto-satisfaction or criticizing the “enemy”. It can be argued these tweets don’t have much significance to speak of. The politicians are not able to reach out to users who do not already share their political conviction (and therefore presumably already following them if they are users of the platform). For why would a left wing user – or even a “neutral” user – bother to look for a right wing politician’s stream (perhaps apart from when the intention is to ridicule or provoke said politician)? The French politicians discussed here seem overall content to stay within their comfort zone. They are, so to speak, preaching to the choir.

This presents a big obstacle for people seeking to advertise or advocate using Twitter. The platform is based on each users’ active monitoring, search of hashtags or profiles to follow; thereby making him or her harder to reach for someone not sharing the same fields of interest, topics of conversation or even subjective take on the same matter. For the political tweets to hit intended target – if we assume the aim is ultimately to gain more votes – politicians might need to broaden their field of discourse, making it easier for “ordinary” users to stumble upon them.