Piracy in the Gaming Industry; Consumers at a Loss

Piracy has been both a key aspect and influencer of the video gaming industry ever seen its conception. It has affected the way in which games are perceived, played, made, and the way in which they are sold. Due to the fear of lost profits, many gaming companies are choosing to adopt alternative means by which they can secure their sales, means which test the limits of the consumers rights. (Although I have written previous posts on the topic of Digital Rights Management (DRM) within different platforms of media, it is still a huge social concern within the communities in which it has been implemented).

This form of ‘counter-piracy’ has been seen in many other more obvious mediums, such as newspapers and magazines, as Johns observes, piracy is not exclusive to the digital revolution (Johns: 2009). However, as a contemporary case study, the platform of gaming can be considered as a recent victim of this distorted media experience. Rather than fulfilling their initial role as interactive entertainment softwares, video games published under these corporations are now focusing upon obstructive ‘informationalised, overcommodified frame(s)’ that disrupt the viewers enjoyment with the product that they have purchased (Sundaram: 2000). These take form as in-game advertisements for in-game products that disrupt the users immersion with their purchase. A certain point arises here regarding Ravi Sundaram’s consideration of surfaces, or more specifically, the surfaces of pirated media objects.

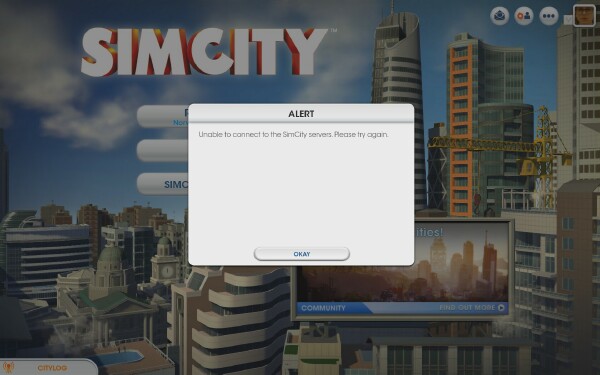

An example of the problems caused by online requirements within games; Maxi’s recent release Sim City preventing the user access during server downtime.

As Sundaram points out (in Revisiting the Pirate Kingdom 2009), Indian companies of the 1980s & 90s would allow cable operators to insert advertising within television and film which bordered the viewers vision, distorting their media experience and ‘transgressing the classic rules of disembodied television spectatorship’, an outcome which Sundaram argues to be a cause of the user’s ‘partaking in the pirate aesthetic’ (Sundaram: 2000). However, this is where the issues arise concerning consumer rights, as it is the legal consumer, rather than the illegal pirate, that is victim to this intrusion, all because of the apparent ‘threat’ piracy has fabricated within the industry of game publishing.

Due to the evident capability hackers have to ‘crack’ certain games (or at least the apparent ease by which games can be pirated and downloaded by the lay Internet user), larger publishers have introduced 3rd party DRM in which an online account is needed in order to play their games unhindered. Another example of publishers attempting to prevent the illegal downloading of their products can be seen in the implementation of intrusive downloadable content features (DLC), meaning that the game a consumer purchases is not complete in its entirety. Whilst this may seem like an obvious method of preventing the piracy of games, it is severely damaging the experience of those who choose to actually purchase the game, rather than pirating its content. Whilst pirates are able to steadily overcome these inclusions of DRM and DLC, the standard consumer is left with excess charges and the need for a constant internet connection in order to gain access to their product.

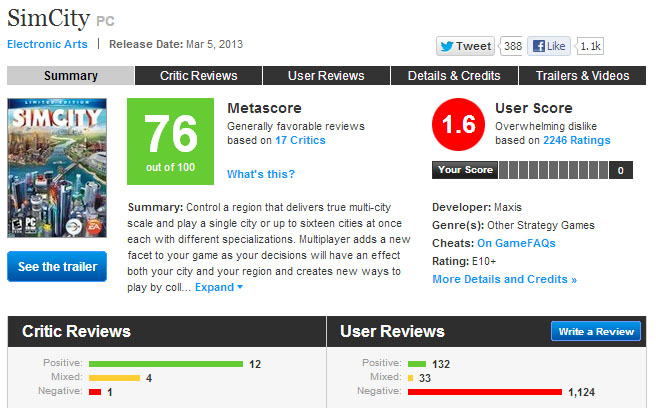

Combining this with the potential for server problems causing users an unforgivable inability to access their games, and the presence of troll hackers who purposefully attempt denial-of-service attacks (DDOS) against gaming servers, it is clear to see that it is only the consumer who is falling short within this problematic, contentious, and hierarchical distribution triangle. It is because of this that piracy is steadily changing the perceptions gamers have of both large publishing companies such as Electronic Arts (EA), as well as gaming distribution in general. This is true to the extent that, due to public outcry and user petitions, Ubisoft recently stated that they would no longer publish games with ‘always-on DRM’.

With regards to a ‘bigger picture’ of sociopolitical change, the increased number of responses made clear by gaming communities concerning the dislocation of the game from its initial purpose run parallel to the ever-rising users of piracy within video game platforms. If consumers are to be punished for the crimes of pirates, then the only sensible options are to petition against the inclusion of DRM and unwarranted DLC (either to a higher political power or the companies themselves), or to become a pirate themselves. It is because of this that the multi-billion entity that is the gaming industry has begun alternative marketing approaches and business models. This is in order to counteract the presence of piracy whilst respecting the rights of the consumer, the success of which has been made evident. Thus, it is within reason to state that the nonlegal consumption of media objects has the ability to influence sociopolitical change through the reformatting of the video gaming industry.

Community response SimCity. The vast amounts of negativity is attributed to the ‘always-on DRM’, a feature typical of products published by EA Games .

References

Adrian Johns, Piracy: The Intellectual Property Wars from Gutenberg to Gates, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009, pp. 1-56.

Ravi Sundaram, ‘Revisiting the Pirate Kingdom’, Third Text 23.3 (2009): 335-345.