iBeacons at SXSW: How technology adds to the festival experience

While beacons have become mainstream since the introduction of the iBeacon by Apple in 2013, there are still fields fairly undiscovered. One of these fields is integrating beacon technology at festivals and events. In march this year (2015) the South by Southwest (SXSW) festival in Texas introduced iBeacon implementation for the first time on a major scale. The festival placed around 1000 iBeacons surrounding its venues that will “fundamentally change attendee’s experiences”. But what does this exactly mean and how does this process work?

since the introduction of the iBeacon by Apple in 2013, there are still fields fairly undiscovered. One of these fields is integrating beacon technology at festivals and events. In march this year (2015) the South by Southwest (SXSW) festival in Texas introduced iBeacon implementation for the first time on a major scale. The festival placed around 1000 iBeacons surrounding its venues that will “fundamentally change attendee’s experiences”. But what does this exactly mean and how does this process work?

Apple’s iBeacon is a big player within the industry. The definition of the iBeacon is stated as follows: “An iBeacon is a Bluetooth Low Energy device that only sends a signal in a specific format. They are like a lighthouse that sends light signals to boats” (Kohne 2014)”. The devices use Bluetooth to connect with each other and can form a network this way by acting as nods within it. The most common purpose of the Beacon is described as “The Beacon can be used for creating a region, known as geofence, around an entity that will allow the iOS or the Android system to identify when it either enters or exits the location” (Zafai & Papapanagiotou 2015). This usage is very comparable to the lighthouse metaphor where a beacon or smartphone is the equivalent of a boat, guided by the physical presence of a beacon or lighthouse. While this is only one usage it demonstrates the basic principle that the (i)Beacon provides: it acts as a bridge between the virtual and the physical world.

The iBeacon technology used at the SXSW is integrated in their own app called SXSW GO which is developed by Eventbase. This is the promo video:

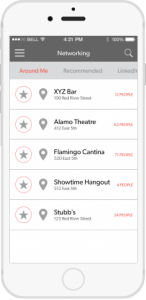

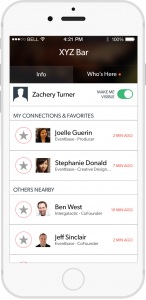

The app provides multiple usage practices that are explained by articles on Mashable, 9to5mac and The Next Web. For example when entering a venue and a certain session, user can enter a chatroom filled with people attending this venue. Users can also see who is around them and what events are going on or coming up nearby. The practical use for the festival attendee is mostly about networking. It is extending the networking experience into the ‘virtual’ and giving opportunities that otherwise would not appear. Such as speaking to all the attendees of an event at once. I think this shows that these new technologies do not only bring the physical interaction to the virtual world, it also opens newer opportunities that outperform the physical world.

“There has long been a discontinuity between the rich interaction with objects in our physical world and impoverished interactions with electronic material. Furthermore, linking these two worlds has been difficult and expensive.” (Harrison et al 1999)

The iBeacon technology exemplified at SXSW is major step in bridging the two worlds that Harrison et al describe. For the organizers it involves labor and financial expenses to provide the platform. So we need to take a look at the benefits for the festival organizers in implementing such a system.

On this side there are some interesting aspects to look at. The SXSW Go app allows for push notifications when needed. This is usually a message announcing an upcoming event. Jeff Sinclair a co-founder of Eventbase said that “We don’t want to spam users or overwhelm them with messages”. While its quantity might not be big the actual value could lie in the content. It could potentially be advertisements involving products at the festival.

See nearby users

Another benefit involves the data mining. This ranges from the chat messages to location tracking. While the feedback here could definitely be used for improving the festival, it also raises the debate about privacy as is described in “The Loss of Location Privacy in the Cellular Age” by Stephen Wicker (2012). One of the main arguments in this article is that “supposedly anonymous location traces can be de-anonymized through correlation with publicly available databases” (Wicker 1). In the SXSW Go app the de-anonymization could be done by including the content of messages or the user information (such as Facebook accounts) directly. These traces might track more information then the app-user is really aware of.

Conclusion

The iBeacon technology implemented in the SXSW Go App extends and exceeds the attendee’s festival experience in a virtual way. It provides new networking ways that can enhance the involvement verbally in the events going on around them and can help them networking with people they want in a more efficient way. The communication is a two way street in which the organizers get valuable data and direct feedback about the festival experiences. Implementing such new technologies sure seem like a win-win situation for the users and the festivals. The bridge between the physical and the virtual is getting more broad but could, in terms of privacy, become more slippery. The debate about data mining is now extending to the physical world in a big way.

Bibliography

- Harrison, B.L.; Fishkin, K. P. ; Gujar, A.; Portnov, D.; Want, R. “Bridging physical and virtual worlds with tagged documents, objects and locations” ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 15-20 May 1999, Pittsburgh. New York: ACM, 1999.

- Kohne, M., and J. Sieck. “Location-Based Services with iBeacon Technology.” 2014 2nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Modelling and Simulation (AIMS). N.p., 2014. 315–321. IEEE Xplore. Web.

- Wicker, Stephen B. “The loss of location privacy in the cellular age.” Communications of the ACM 55.8 (2012): 60–68.

- Zafari, F. and I. Papapanagiotou. “Enhancing iBeacon based Micro-Location with Particle Filtering”. IEEE GLOBECOM. Purdue University, 2015