The Lebanese Hashtag War: People vs. Government

Like many of the Arab Nations that surround it, Lebanon has fallen into the hands of an escalating social revolution. The Lebanese population began voicing its discontent towards their government about the garbage that has been piling up, since July 19, 2015, on the streets of Beirut (Lebanon’s capital) through a hashtag known as “#طلعت_ريحتكم” (equivalent to #YouStink) and was used as a slogan for the #YouStink campaign against the garbage issue.

But as the situation began to intensify, the hashtag’s meaning evolved.

Garbage, the Symbol of Corruption

Lebanon is a country that has experienced many years of political turmoil and corruption; what with a Sectarian government that can never agree on anything (set-up by the French post-WWII), partisanship, a 15-year Civil War, and current Presidential vacancy (among MANY other things).

These political issues continuously created a schism between the Lebanese populous, as each one followed their “own” leader/party (based on their particular religion, sect, or region), which, in turn, instigated protests opposing the other’s party.

But for the first time, Lebanese people went down to the Parliament building in Downtown Beirut on August 19, 2015, not to show their dislike to a particular political party, but to peacefully protest the Government’s lack of attention towards the country’s garbage crisis.

The result?

This exact moment was what instigated the different meaning behind #طلعت_ريحتكم. The protesting went from being directed towards a solution for the garbage situation to asking every current member of the Lebanese Parliament to step down. It was the anger and frustration of the people that caused this sudden shift.

The hashtag’s meaning was changed by the protesters, not in a negative manner, rather in an extensive manner that covered all of the socio-economic issues the country is facing besides that of waste and from it came more hashtags like #مستمرون (‘we will continue’), #بدنا_نحاسب (‘We want accountability’), and كلن_ يعني _كلن# (‘All of them means all of them’). At this point, the people had had enough of its government. The increased use of the hashtags was a symbol of unification, free from any political affiliation.

However, as the protests increased, the targeted politicians took upon themselves to also use the hashtag, but in this case, their attempts were clearly one-sided and self-promotional.

Joining the Trend

Hashtags and activism seem to go hand in hand these days. Its not a secret that with the increasing use of social media platforms, hashtags have become the mediators and links between users. The purpose of a hashtag is to allow people to relate to certain topics, giving them a chance to be seen (Page, 2012, 184).

Like any attention-seeking Twitter or Facebook user, some of the Lebanese politicians under fire thought it wise to hijack the #YouStink campaign’s hashtag as a way to shed light on their message; an action done by ISIS (Islamic State) (Veilleux-Lepage, 2014, 10) to spread their message and by companies or celebrities to promote themselves/brand (Page, 2012, 198) via popular hashtags at the time.

A few examples of the politicians using the hashtags:

A screenshot of a Twitter post by Dr. Samir Geagea (head of the Lebanese Forces, political party) using the hashtags to spread his desire to elect a president (that follows him, of course).

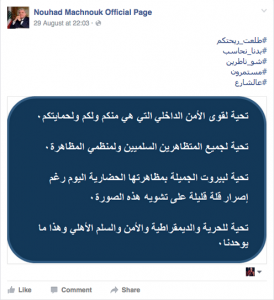

A screenshot displaying Nouhad Machnouk (Lebanese Minister of Interior and Municipalities) using the hashtag as a way to ‘redeem’ police brutality during the protests.

A screenshot of General Michel Aoun (leader of Free Patriotic Movement) Facebook post demonstrating his ‘support’ for the #YouStink campaign by organising his own protest, but using one of the other hashtags which translates into ‘All of them means all of them.’

In this case, the use of the #YouStink campaign’s hashtags for political purposes had both negative and positive reactions from the population.

On the one hand, you have many who criticised or mocked the politicians for using these anti-parliament hashtags:

Screenshot of Shaden Fakih’s (protestor) post mocking General Michel Aoun’s request for his followers to protest the government.

Screenshot of the Twitter mocking responses Dr. Samir Geagea received after posting his tweet (see above).

On the other hand, you have many Lebanese people who still follow their leader and went down to protest in support of him, in this case, General Michel Aoun (Free Patriotic Movement founder), who’s son-in-law is the current head of FPM, former Minister of Communications and of Energy and Water. Aoun saw an opportunity and managed to bring down thousands in support of him.

Up until now, Lebanon’s social revolution is still going on as solutions have yet to be made by the government. As the members of parliament refuse to step down, #YouStink campaign will continue to protest the corrupt government on the streets and online as they spread their message to the masses internationally. The campaign protests have reached New York, Paris and London, all of them using #طلعت_ريحتكم.

References:

Page, R. “The Linguistics of Self-Branding and Micro-Celebrity in Twitter: The Role of Hashtags.”Discourse & Communication 6.2 (1 May 2012): 181–201.

Veilleux-Lepage, Y. “Retweeting the Caliphate: The Role of Soft-Sympathizers in the Islamic State’s Social Media Strategy.” 6th International Symposium on Terrorism and Transnational Crime. Antalya, Turkey. Online: ResearchGate, Dec. 2014. 1–15.