Trust Me: How Trust is Established in Airbnb

The financial crisis in 2008 marked the advent of the sharing economy, and its motto “access trumps ownership” (The Economist) came out as a good option to deal with the crisis which mainly occurred as a result of the excessive consumption (Henten, Windekilde 5). But to describe the sharing economy, it is necessary to look at different definitions since it is an emergent marketplace that has been developing and changing continuously.

Sundararajan describes the sharing economy as a combination of both commercial and social activity (39). In other words, people do not only provide and buy goods and services, but also establish closer connections, maybe become friends and share further interactions. This social and cultural role of the sharing economy is one of the most important features that distinguishes it from the earlier marketplaces. Moreover, Botsman in her TED talk points out to another important aspect of the sharing economy by describing it as a “social and economic activity driven by network technologies”. Thus, new media technologies facilitate the most essential activities of the sharing economy.

According to Sundararajan, there are five distinctive characteristics of the sharing economy. First of all, the sharing economy fosters economic activities by making both goods and services possible to exchange. This leads to “high-impact capital” which means that every asset can be capitalized and used in “their full capacity”. As the variety of assets – including both goods and services – are expanded, the provision of the money and workforce becomes “decentralized”. Furthermore, the expansion of the type of assets provided by the sharing economy also weakens the boundary between “personal” and “professional”. Many peer-to-peer activities that are regarded as “personal”, such as sharing your house or giving someone a ride, have become a professional activity that help people make profit. Lastly, unlike the traditional markets, the type of labor practiced in the sharing economy does not necessarily require long-time responsibilities and “continuum” which effaces the distinction between work and leisure (Sundararajan 40).

Considering these features of the sharing economy, it is clear that several advantages have been brought by the successful platforms in this economy. Botsman and Rogers express the value of the sharing economy as “the enormous benefits of access to products and services over ownership, and at the same time save money, space, and time; make new friends; and become active citizens again” (qtd. in Henten, Windekilde). Apart from these, the sharing economy has also introduced new transaction options that reduce the costs. For instance, with the help of network technologies, it is considerably easier to search for a right place to stay or find the most convenient means of transportation.

However, the sharing economy has also engendered risks which are mainly caused by the trust issues. Ert et. al suggests that because services provided by the sharing economy platforms are “produced and consumed simultaneously” (63), people cannot know what to expect, so there is a risk in terms of money. As every step in this exchange process takes place online, people risk more than money which increases the importance of trust immensely. Staying in a complete stranger’s house, or sharing a ride with someone we do not know raises the question of safety.

As Sundararajan indicates, the definition of trust can change according to the context, so he proposes James Coleman’s definition as the most suitable one: “a willingness to commit to a collaborative effort before you know how the other person will behave” (79). Therefore, what causes people not to trust someone is mainly the information asymmetry which refers to the situation where different sides do not have the same amount of knowledge (Finley 17). Thus, the more people know about what kind of service they get, or from whom, the more trust can be built.

Airbnb as a case study

To understand how platforms overcome this information asymmetry we decided to look into one of the most prominent pioneers of the sharing economy, namely Airbnb. Airbnb identifies itself as “a trusted community marketplace for people to list, discover, and book unique accommodations around the world” (Airbnb.com). In simpler terms, Airbnb encourages people to invite strangers to their homes and stay at strangers’ places, with relatively unknown consequences. In view that people – or guests and hosts – who engage in such activities get to know and trust each other exclusively through mediation of Airbnb, we argue that the study of this platform will help to understand how trust is established in such newly evolved marketplaces.

In order to overcome information asymmetry, Airbnb provides several services such as building a reliable reputation system which includes reviews, trustworthy pictures and visuals, smooth transactions, and also incorporating social media accounts is an effective way to reduce the information asymmetry.

In the aforementioned self-description, Airbnb itself also recognizes that trust plays a major role in platform’s operations. Joe Gebbia, one of Airbnb’s co-founders, particularly regards reputation to be the key factor for building trust between hosts and guests (TED). He believes that high reputation based on reviews helps to overcome natural social biases that people tend to have toward strangers. To take it a step further, reputation nowadays can be considered to serve “not only as a psychological reward or currency, but also as an actual currency – called reputation capital” (Botsman and Rogers 337). According to Botsman, reputation capital is gained through participation in collaborative consumption, and the more reputation capital we earn, the more we can participate (338).

It is true that highly ranked Airbnb hosts get more reservations and guests with positive reviews are less likely to get their booking request cancelled (Newman and Antin). Yet, one cannot help but notice that novice users who lack an established reputation can too engage in transactions and reap the benefits of this sharing community. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that other factors that allow individuals to overcome trust barriers and engage in home-sharing interactions may also be at play here.

Visualising the development of trust in Airbnb

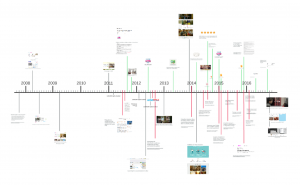

In attempt to conveniently convey the possible factors that contribute to establishment of trust, a visual timeline seemed like a logical solution. After all, building trust is likely to be a continuous process that also takes time.

The resulting trust timeline encompasses the period from the creation of Airbnb’s first prototype (Designer’s IDSA Connecting Guide) in October 2007, when co-founders Joe Gebbia and Brian Chesky rented out airbeds in their apartment to other visitors of the event, until the present. It is comprised of:

- screenshots of Airbnb’s homepage at www.airbnb.com and other important subpages to capture interface changes;

- newly introduced or changed features and policies of the platform;

- some of most notable problems Airbnb encountered in course of its development and the company’s responses.

With regard to the last point, we focused on incidents that went public and could potentially damage company’s profile globally.

Additionally, some other interesting points, such as nights bookings’ milestones reported by the Airbnb, emergence of Airbnbhell.com and the time of platform’s rebranding, were included to set up context.

We offer several paths through which to explore the timeline. These pre-created narratives focus on specific aspects of building trust – through visuals, through added functionality and rules, and through company’s reactions to different events. The timeline also allows to see a whole picture of the events “negatively” affecting Airbnb and Airbnb’s “positive” reactions. This view is accessed by pressing the “Show overview” button. From here, users can also zoom into particular elements themselves and move between slides discordantly. We believe, such free interaction with the timeline will allow users to find their own view on the meaning of various developments that took place on Airbnb over time, independently establish possible correlations and form their own opinion about the company and its dealings with trust.

The timeline is published publicly on the Masters of Media blog and Prezi platform and is thus accessible to anyone interested in how trust relations are being established in the sharing economy and how this works at Airbnb in particular. It can also be seen as a tool that could help others companies understand what constitutes participation in the sharing economy and what sort of problems should be anticipated.

Chronological Timeline

Features and Policies

Evolution of Design

Incidents and Responses

Findings

The timeline shows how a fast growing platform such as Airbnb copes with all the elements that are related to trust. When looking at the timeline we see several moments in time where problems with Airnbnb surface, for example the death of a woman due to carbon monoxide poisoning or the stories of vandalized apartments. Some time afterwards new additions were made to Airbnb that might have solved some of the stated problems. It then seems plausible that the level of trust towards Airbnb is in a constant flux.

When we looked at the design changes made to Airbnb’s homepage over the years, it became obvious that photography has grown to be a central element. While in the beginning the images were produced by users, the current website uses only high-quality material, and these visuals take up way more space on all of the pages than before. This seems to coincide with the theory of “visual based trust” (Ert et al.) that has focused on the effect of imagery on user perception of the platform. The research suggests that using images in a substantial amount would meet the hosts’ needs for personal interaction (69).

Our research also revealed several developments that were introduced to the platform in response to unfortunate Airbnb experiences that gained a lot of media attention. For instance, after the a blog post about a trashed apartment went viral, Airbnb added Trust & Safety section to its website and introduced its Host Guarantee policy. And while Airbnb’s reaction to such events may seem appropriate, it nevertheless raises the question of why the company had not been proactive in preventing certain disasters in the first place.

During the research, we have also noticed that in the last two years Airbnb has incorporated its pages devoted to safety into “trust pages”. This seems to be be telling the world that for Airbnb trust is the main element in creating a safe environment for its users. At the same time, it must be noted that Airbnb has done a lot to improve safety.

Limitations

We recognize that the timeline is far from being an exhaustive record of all of the events that could influence trust. We had to rely on our evaluation skills in assessing what information is to be put up on the timeline and what information had to be left out in view of our research topic. Moreover, as some things are not being disclosed by Airbnb, we were able to only use information that made its way out in the open.

It is also difficult to determine whether there actually is any cause and effect relation between two seemingly connected events on the timeline. Establishing this as a fact would only be possible through people involved confirming the story and backing it up with evidence. In the meantime, we can only speculate.

Even though we consider Prezi to be one of the most useful tools for creating presentation-based visualisations in a short period of time, we also recognize its limitations which were reflected in the aesthetics and functional capabilities of the timeline. A diverse colour palette, more text editing options and broader slide customization features could have all helped to produce richer and clearer narratives.

Bibliography

About us. Airbnb. 18 October 2016. <https://www.airbnb.com/about/about-us>

“All Eyes on the Sharing Economy.” The Economist. 9 March 2013. 6 October 2016. <http://www.economist.com/news/technology-quarterly/21572914-collaborative-consumption-technology-makes-it-easier-people-rent-items>

Botsman, Rachel, and Roo Rogers. What’s Mine Is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption. Harper Collins ebooks, 2010.

Botsman, Rachel. “The Currency of New Economy is Trust.” TED. June 2012. 21 September 2016. <https://www.ted.com/talks/rachel_botsman_the_currency_of_the_new_economy_is_trust>

Ert, Eyal, and Aliza Fleischer, and Nathan Magen. “Trust and Reputation in the Sharing Economy: The Role of Personal Photos in Airbnb.” Tourism Management 55 (2016): 62–73.

“Designer IDSA’s Connecting Guide.” Internet Archive Wayback Machine. The Internet Archive, 2016. 11 October 2007. <https://web.archive.org/web/20071011030642/http://airbedandbreakfast.com>

Henten, Andersen, and Iwona Maria Windekilde. “Transaction costs and the sharing economy.” info 18.1 (2016): 1–15.

Newman, Riley, and Antin. “Building for Trust: Insights from Our Efforts to Distill the Fuel for the Sharing Economy.” Airbnb Engineering. 29 March 2016. 24 September 2016. <http://nerds.airbnb.com/buildingfortrust>

Sundararajan, Arun. The Sharing Economy: The End of Employment and The Rise of Crowd-Based Capitalism. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2016.

TED. “How Airbnb designs for trust | Joe Gebbia.” YouTube. 5 April 2016. 20 September 2016. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=16cMRFid9U>