ReplyASAP: A Quick Fix for Ignored Parents

It comes without question that having a mobile phone as a child or a teenager is essentially a must in today’s society. Many reasons could apply to answering why, from playing games, sending funny Snapchat videos to their friends to uploading new photos on Instagram. From a parent’s perspective though, the number one reason to own a cell phone is possibly the fact that they can reach their child anytime. According to debate.org, on whether children should have cell phones, 70% percent of people said yes. One parent specifically went on to make their point:

When kids have cell phones, they feel safer and you can get a hold of them. If you are a parent like me, you would want to know your kid or kids are safe at home, not getting kidnapped and not being able to call you!

Integration of mobile technology in teenagers’ lives is leading to new paths of interaction between them and their families. Many surveys and research have been conducted to further examine the impact on teenage and family communication. According to Valkenburg and Piotrowski, “media play a functional role in the family by regulating household routines, facilitating family members’ communication, and even physically organizing family members within the house” (249). This view is also clear from a survey carried out among teenagers, some of whom confirmed that they use it to make plans with their parents, such as asking them to stay longer at their friends’ house or asking them to pick them up (Devitt and Roker 192).

Nonetheless, the use of media and platforms and the time spent on them has also been criticized as negatively influencing the kind of communication relationship built among family members (Moawad and Ebrahem 174). Sometimes being a teenager means putting greater emphasis on what your friends think of you, having parents fall down in the list of priorities. As Valkenburg and Piotrowski put it, teenagers have a tendency “to struggle with limits, and to place a greater value on peers than on parents or other family members” (261).

So sometimes, even when they receive a call or text from their parents, teenagers tend to avoid answering, thus making it frustrating for a parent, who is unable to know if there is an actual emergency going on or if the child is simply ignoring the call.

The answer for ignored parents

Nick Herbert had been experiencing this problem with his son and claims he has the solution. It’s called ReplyASAP app. As he explains in the application website, his son would play games or watch videos on his smart phone, even on silent mode, making it impossible for his father to get hold of him. The abundance of messaging apps does not necessarily mean that they forward communication, as messages can still be ignored, even though the sender is aware that their message has been delivered. According to Herbert, this application is able to overcome such communication boundaries.

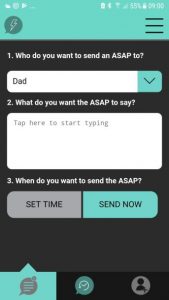

What you can do via this application is send a message which completely covers the recipient’s screen, irrespective of what they are doing on their phone at that moment. An alarm sound is also set off at the same time – even if the phone is on silent mode. The only way to stop the sound is to interact with the options available on the screen; either to Cancel or Snooze for 3 minutes – in which cases, the sender will have a status message of ‘Seen’ or ‘Snoozed’ respectively. If the recipient – in this case the too-bored-to answer teenager – shuts off their phone, then the sender will receive a Pending status on their phone. The same applies if the recipient does not have an Internet connection, as it is required for the app to be used. The application is free of charge, and the user can connect to one person for free, yet if one wishes to include additional contacts, there will be extra costs.

Herbert suggests that people use the application responsibly, not as one more messaging application, but rather as a last resort in an emergency situation. “ReplyASAP is only for important things”, he says. And yet, who is to decide what is important or not? Is an application like ReplyASAP the solution to ignored parents?

The app enables the user to send the message on the spot or at a set time.

A solution or a new problem?

On the one hand, ReplyASAP is another example of how new technologies are used within a household, and could be the aftermath of the different perspectives parents and teenagers have, when it comes to the use of mobile phones. This is even enhancing the view that a mobile phone, apart from anything else, is a safety measure. Having a mobile phone makes teenagers feel less at risk when they are outside the house, “described as both a back-up measure and a lifeline” (Devitt and Roker 196). Apart from that, it is a means of control, since “[t]he parent uses the mobile phone to enter into teenage space, and as the absent other can influence the behavior and social space of the teenager” (S.Williams and L.Williams 322). New technology has created a whole new framework of communication, because texts do not seem as invasive and teenagers tend to have a more positive inclination to it, compared to other forms of communicating with their parents (S.Williams and L.Williams 326). However, when it comes to their own use of new technology, “[teenagers] see media as part of their personal domain”(Valkenburg and Piotrowski 260-261), and are led to disregard parents’ efforts to communicate with them on purpose. Even though it is supposed to be used in emergency situations, ReplyASAP seems to be much more than that. It is an effort to bridge the gap. In other words, it is a parental effort to be present in their children’s social life out of the house.

On the other hand, it seems as if this app is opening up a whole new phase of devices forcing us to interact with them. We have come to accept that smart technology is an integral part of our lives now, aiding in maintaining a feeling of connectedness. However, a more skeptical perspective will unavoidably lead us into questioning whether such an application is actually a solution or if it is creating more problems that will in turn ask for more solutions. It cannot be said that there are no good intentions behind this idea. It could be argued though, that miscommunication between family members is an issue that should be looked upon through various social and psychological perspectives. A quick technological fix does not seem to be an appropriate answer. On the contrary, it seems to raise more concerns, such as intrusion and control issues. Therefore, it would be appropriate to claim that such an app falls under the category of technological ‘solutionism’, to borrow Evgeny Morozov’s term. As Michael Dobbins suggests, “solutionism presumes rather than investigates the problems that it is trying to solve, reaching for the answer before the questions have been fully asked” (Morozov 16). In order to solve the problem, the reasons and the conditions under which the problem was formed should also be taken into account (Morozov 16). Consequently, we should investigate on the reasons that lead teenagers to ignore their parents’ messages in the first place. It is not only the media and technology that may fascinate teenagers so much as to avoid their parents, but other social factors as well. For example, as Herbert claims in the app website, being embarrassed to talk to your parents in front of your friends.

Furthermore, the app raises issues of intrusion, because it coerces a form of interaction, even in situations that we do not want to be bothered. Brenda Stolyar gave her own personal account of using the application in DigitalTrends, making a point about the invasive issues raised by its use: “There’s probably nothing more embarrassing than being at the movies or at a party only to have your phone loudly and uncontrollably go off”. What’s more, if the app is used in other contexts, for example as a means of emergency communication between co-workers, how would the people involved reach an agreement in terms of its usage?

Conclusion

To conclude, ReplyASAP certainly gets its point across, in the sense that it is designed to avoid being avoided. However, it raises issues of intrusion into one’s personal space and it is unclear under which circumstances it could be used properly. It could be claimed that the app reminds us that we should look into a social problem in many different angles and perspectives before deciding on a solution, and certainly not resort to a quick technological fix. As Weinberg suggests, “[i]t is only by cooperation between technologist and social engineer that we can hope to achieve what is the aim of all technologists and social engineers – a better society, and thereby a better life, for all of us who are part of society” (8).

References

Debate.org. 2007. Juggle LLC. 21 September 2017. <http://www.debate.org/opinions/should-children-have-cell-phones>

Devitt, Kerry, and Debi Roker. “The Role of Mobile Phones in Family Communication.” Children & Society 23.3 (2009): 189–202. 5 September 2017. < http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/wol1/doi/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2008.00166.x/full>

Moawad Ahmed G.N., and Gawhara Gad Soliman Ebrahem. “The Relationship between use of Technology and Parent-Adolescents Social Relationship.” Journal of Education and Practice 7.14 (2016): 168-178. 5 September 2017. <http://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/JEP/article/view/30653>

Morozov, Evgeny. To Save Everything, Click Here. The Folly of Technological Solutionism. New York: PublicAffairs, 2013.

ReplyASAP Messaging App. 2017. 5 September 2017. <http://www.replyasap.co.uk>

Stolyar, Brenda. “ReplyASAP App for Android is a Teenager’s Worst Nightmare.” Digital Trends. Ed. Jeremy Kaplan. 2017. 6 September 2017. <https://www.digitaltrends.com/mobile/replyasap-app-attack>

Valkenburg, Patti M., and Jessica Taylor Piotrowski. “MEDIA AND PARENTING.” Plugged In: How Media Attract and Affect Youth. New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2017. 244–266. <www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1n2tvjd.17>

Weinberg, Alvin M. “Can Technology Replace Social Engineering?” American Behavioral Scientist 10.9 (1967): 4-8. 21 September 2017. <http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0002764201000903?journalCode=absb>

Williams, S., and Williams, L. “Space Invaders: The Negotiation of Teenage Boundaries through the Mobile Phone.” The Sociological Review 53.2 (2005): 314–331. 5 September 2017. <http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/wol1/doi/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2005.00516.x/full>