Is Vidme the ‘NewTube’? Why video creators are changing sides and how they feel about it

A few weeks ago on September 9, video platform Vidme’s own channel uploaded their weekly episode of ‘This Week @ Vidme’ titled ‘German INVASION’. The video refers to a sudden and significant increase of German led channels on Vidme: According to the video almost 100.000 new creators from Germany had joined the platform over a short period of time. How did this relatively small video platform suddenly become so popular amongst German users?

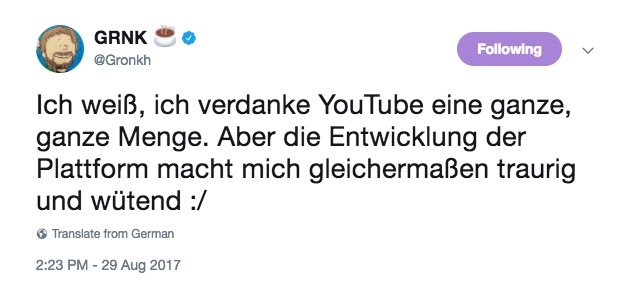

Image 1: Screenshot of one of Gronkh’s tweets on YouTube (Translation in the text) | Source

Vidme gained a lot of popularity in Germany when famous gaming YouTuber Gronkh announced on Twitter that he would be re-uploading the click-and-point adventure series ‘Edna Bricht Aus’ on Vidme. Before, YouTube had seemingly deleted some recordings of the same game for no apparent reason, flagging others as ‘not advert friendly’.

Gronkh who currently has more than 4,6 million subscribers on YouTube and is one of the most influential video creators in the German gaming scene decided to move to Vidme – and thus caused an avalanche of other creators to follow his lead. In one of the related tweets Gronkh stated: “I know that I owe a lot to YouTube. But the development of the platform makes me sad and angry at the same time.”

Apparently, he is not the only one feeling like that.

The aftermath of the ‘Adpocalypse’

The growing dissatisfaction of YouTube content creators with their home-platform is not at all a new phenomenon nor is it only limited to the German speaking community. The development can be seen as a symptom to an ongoing commercialization and institutionalization process that arguably started when YouTube was taken over by Google in 2006 (cf. Kim 2012). According to Kim, the result of this process is a “hegemonic tension between an amateur-led, individual-driven alternative mediascape and a professional-led, institution-driven traditional mediascape” where YouTube becomes more and more concerned with ‘ad-friendliness’ rather than ‘creator-friendliness’ (Kim 2012: 54). For further information on that topic I recommend this article by Pija Indriunaite on the MoM blog.

The debate took a new turn in March this year when big companies pulled their adverts from YouTube after some had apparently been placed next to offensive content. In the aftermath of the so called ‘Adpocalypse’ YouTube strongly tightened their ad policies demonetizing many videos or even deleting them for featuring “graphic, edgy or sensitive imagery and text” (Patel 2017). However, many videos were flagged or deleted without notifying the creators or clearly stating why, which left many YouTubers in a state of sheer bewilderment (cf. Patel 2017).

As described by Postigo (2016: 333), the video creators are part of the “digital labor architecture” of YouTube and as such often dependent on the share they receive from advertisement revenue. Therefore, the consequences affected many YouTubers around the world but especially smaller channels as their ad-revenue decreased considerably (Patel 2017).

Image 2: Screenshot of YouTube creator ‘INC_Smoothie’ asking his Twitter followers to follow him on Vidme | Source

As a result of the ‘Adpocalypse’ and many other changes the platform recently implemented on both front-end and back-end, YouTube has become a subject of lively discussion and critique amongst users and creators likewise. International YouTube personalities like Pewdiepie or Philip DeFranco published videos on the issue, DeFranco claiming that YouTube is “pushing creators away”. Throughout Social Media hashtags like ‘#wtfyt’ or ‘#adpocalypse’ are used to share opinions. Also, many video creators – like Gronkh – looked for an alternative way of distributing and monetizing their content and found it in the video platform Vidme.

Vidme – YouTube as it should be?

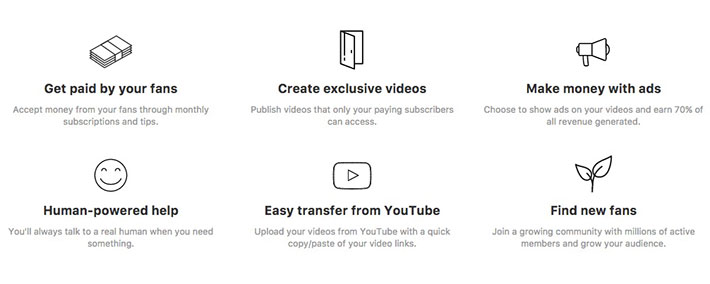

Even though the platform is not ‘new’ – it was founded in 2014 – Vidme’s newly gained popularity makes it an interesting subject of examination. According to their website Vidme currently has more than 25 million monthly users. The network’s self-proclaimed goal is “to build the world’s most creator-friendly video community” (Vidme). It becomes apparent that the social network tries to position themselves as a young and independent counterpart to their ‘older brother’ YouTube. So what differentiates the two social networks?

On the face of it, not much. Both Vidme and YouTube are community-driven video sharing platforms, allowing their users to publish their own video content online, rate, share, comment and monetize it (cf. Snickars and Vonderau 2009). However, as Bucher and Helmond (2018: 19) describe, Social Media platforms with particular features afford different action possibilities to different actors with different aims and agendas, such as creators, end-users or advertisers. Seen through the lens of its affordances, Vidme offers a unique set of action possibilities to its users and creators, enabling and constraining certain practices.

Image 3: Screenshot from the Vidme website | Source

Technological affordances

Regarding its technological properties Vidme is often described as a mix of the social news aggregation website Reddit and YouTube: Whereas YouTube offers a ‘like’ and ‘dislike’ function, videos on Vidme can only be ‘upvoted’ which gives these videos more relevance on the website. Like platforms Patreon or Twitch, Vidme also offers a tipping-system as well as a subscription-based model as an alternative to the heavily criticised ad-based monetizing system on YouTube. This enables users to support their favourite video creators directly whilst additionally gaining access to exclusive content and rewards (Kiberd 2017).

Vidme clearly caters to alternative-seeking YouTube creators by facilitating an easy transfer system from YouTube to Vidme. Moreover, the site states to have ‘real humans’ communicating with their creators instead of ‘robots’ (Vidme). In an ironical response to the changes on YouTube Vidme also published a video claiming “Vidme doesn’t censor content for bad language or controversial subject matter. We like weird. Start your fucking awesome channel today!”

According to Bucher and Helmond (2018: 22) “people’s expectations and perceptions of technology may affect behaviour as much as its material properties may do.” Thus, it is also crucial to take into account the affective and emotional elements of affordances.

Imagined affordances

Nagy and Neff (2015) use the term “imagined affordance” to describe how “users may have certain expectations about their communication technologies, data, and media that, in effect and practice, shape how they approach them and what actions they think are suggested” (Nagy and Neff 2015: 5). Certain expectations and emotional experiences shape the way in which users interact with and evaluate technologies, as the example of Vidme illustrates.

Image 4: Screenshot of YouTuber GenerikB expressing his emotions about YouTube’s development in a video | Source

For many of the YouTube creators the platform’s recent changes seem to stand for much more than only stricter ad policies and less revenue. Looking at videos, blog posts and comments on the topic it becomes apparent that the debate is mainly related to strong emotions: In light of the institutionalization and commercialization process of YouTube (cf. Kim 2012) creators feel let down and disappointed by the network and express their resentment in different ways. For instance, YouTuber GenerikB says in his video titled ‘An Open Letter To YouTube…’: “I wanna talk about how YouTube is straight from the path, how they’ve forgotten their roots, where they came from and what allowed them to be the huge channel that they are today.”

In this context the choice of medium can afford a form of agency. As Bucher and Helmond (2018: 2) state: “Pressing a button means something; it mediates and communicates.” It seems to be very likely that many creators ‘pressed Vidme’s registration button’ not only because of the different technological features it offers but also to make a statement against YouTube’s practices. To the disappointed YouTube creators Vidme affords a way of putting pressure on YouTube. As one Reddit user puts it: “I liked YouTube. I still do. But I would really love from them to get some serious competition to make them fear their creators and customers again. Go get ’em!“

Becoming NewTube

In the past there have been many video platforms competing with YouTube’s hegemony but none actually managed to pose a threat to the giant network. Will Vidme be the one to conquer the throne in the end? To me, that seems unlikely. As I have discussed in this article, Vidme clearly benefits from the current emotionally charged debate around YouTube. I assume that apart from its technological affordances users like Gronkh also turn to Vidme for affective reasons. Hence it is questionable if its success will last.

The ‘German Invasion’ seems to be a time-limited phenomenon. And so far most of the creators, German and international, only use Vidme as a ‘second stage’ to mirror their content that is also still being posted to YouTube. But even if Vidme could replace YouTube in the future – it would probably also be subject to the same business developments “negotiating and navigating between community and commerce” (Snickars and Vonderau 2009: 11).

This article touched many issues that in my opinion are well worth to be further examined. The progressing institutionalization of YouTube and the sudden popularity of Vidme as an alternative video platform raise interesting questions about how content creators perceive the changes on the platform and how they create spaces of agency whilst being part of the digital labor infrastructure themselves.

References

All links were last accessed on 09-24-2017

Bucher, Taina/ Helmond, Anne (2018) The Affordances of Social Media Platforms. In: The SAGE Handbook of Social Media, edited by Jean Burgess, Thomas Poell, and Alice Marwick. London and New York: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Kiberd, Roisin (2017) Vidme Is the Latest Challenger to YouTube’s Dominance. Motherboard. URL: https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/wjq48w/vidme-is-the-latest-challenger-to-youtubes-dominance

Kim, Jin (2012) The institutionalization of YouTube: From user-generated content to professionally generated content. In: Media Culture & Society. 34(1). 53-67.

Nagy, Peter/ Neff, Gina (2015): Imagined Affordance: Reconstructing a Keyword for Communication Theory. In: Social Media + Society. July-December 2015. 1-9.

Patel, Sahil (2017) The ‘demonetized’: YouTube’s brand safety crackdown has collateral damage. Digiday UK. URL: https://digiday.com/media/advertisers-may-have-returned-to-youtube-but-creators-are-still-losing-out-on-revenue/

Postigo, Hector (2016) The socio-technical architecture of digital labor: Converting play into YouTube money. In: New media & society. 18(2). 332–349.

Snickars, Pelle/ Vonderau, Patrick (2009): Introduction. In: The YouTube Reader, edited by Pelle Snickars and Patrick Vonderau. Stockholm: National Library of Sweden.

Vidme (2017) About Vidme. URL: www.vid.me/about