Using Personal Data to buy Art: The Data Dollar Store

Recently, Kaspersky Lab has been in the news due to so-called suspicious activity within their security software system and a supposed link with the Russian government. Both TechCrunch and Wired state that the Department of Homeland Security has “banned the US government’s use of all software sold by the Russian security firm Kaspersky”. Although Kaspersky Lab is being over-flooded with “negative” press, at the start of this month they initiated an interesting concept called, The Data Dollar Store. The Data Dollar Store is a store where you can buy a product and piece of art in exchange for your personal data. The focus of this piece will be on this concept of data privacy and their practices of selling an online immaterial security product through the means of a real-life/tangible pop-up store. Is this becoming a new method of attracting and engaging with people about current data privacy issues? Or is this just a marketing stunt by one of the top 5 securities software firm?

Kaspersky and Ben Eine

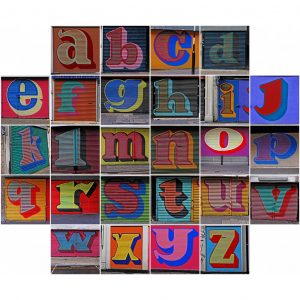

Kaspersky Lab is a 20 year old Russian global cyber security firm with headquarters in Moscow but is operated from the United Kingdom. They have been acknowledged as one of the top cyber security software firms in the world as they “transform deep threat intelligence and security expertise into security solutions and services to protect businesses, critical infrastructures, governments and consumers around the globe”, as they say so themselves (Kaspersky.com). Their products include “total security” to “antivirus” to “kids safe” software. Kaspersky collaborated with British artist Ben Eine on this pop-up store project. Eine is a respected street artist from London who is known to have worked together with Banksy. His signature artwork is a series of alphabet letters that have been graffitied on several shop shutters as well as walls all over Europe. Besides his street work, his works have also reached the White House as well as Downing Street (The Guardian). The combination between urban street-art and global superpower may seem somewhat farfetched, however, the concept of the pop-up store has the ability to trigger a wide range of reactions on the issue of data privacy. The concept of this pop-up store is based on the transaction between personal data and art. The practice of being able to physically buy a product and art-piece with your own personal data, tries to bring the intangibility of data into a physical reality which adds to the current debate about online data privacy.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/lwr/4877977913

https://www.flickr.com/photos/lwr/4878043823

The Data Dollar Store

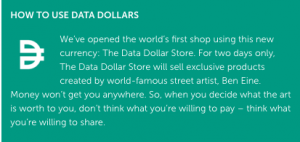

The Data Dollar Store was a two day pop-up store located in the city centre of London at Old Street metro station, a perfect location to catch thousands of eyeballs to raise awareness about the value of personal data. The way The Data Dollar Store worked according to Fortune and Engadget was that the products such as mugs, t- shirts and screenprints made by artist Ben Eine were on sale for a certain price. The way these artworks were to be paid for was by customer’s personal data, also called “Data Dollars”. Each product had a different price. For instance, if one wanted to buy a Ben Eine mug “you would have to hand over three photos, screenshots of your WhatsApp, SMS or e-mail conversations, to Kaspersky”. But if one wanted an original print you would be “forced to hand over your phone”. The team of staff would then be free to select five photos or three screenshots. There would be room for discussion but ultimately it would be their choice of what they would pick (Engadget.com). These practices are supposed to stress how online behaviour and real-life/day-to-day behaviours are similar yet also very different. Buying a product online can be done rather anonymously, but the fact that your Data Dollars would be publicly displayed on the screens of the store for a couple of minutes made the impact of using your personal data for consumption much more visible than the online experience of consumption. This visual representation seemed to be somewhat of a hurdle for people. Exactly the point that Kaspersky and Eine wanted to stress.

https://www.datadollarstore.com/

Data privacy

There are several different ways of viewing (online) privacy. Helen Nissenbaum defines the term privacy as having three different principles. In her article, “Privacy as Contextual Integrity” she explains that the first principle of privacy is about “protecting privacy of individuals against intrusive government agents” where she states that data gathering and surveillance are the forms of action that governments take in order to “stem” the public (Nissenbaum 107). The second principle is focused on the nature of the data and information gathered. She states that restricting as well as defining what “sensitive information” is, is of utmost importance. The last principle is focussed on the question of public and private space, “a person is sovereign in her own domain” (112). Nissenbaum claims that these three principles define the value of privacy whereafter she introduces a concept called “contextual integrity”. Contextual integrity is constructed on two types of informational norms: appropriateness and flow or distribution. Appropriateness refers to types of private information, that within a given context, can be revealed (or not at all). Flow or distribution refers to information that is shared among respected and trusted subjects since it is a choice to share this information bidirectional. However there are many different types of informational norms depending on the subjects involved. Therefore according to Nissenbaum: “a normative account of privacy in terms of contextual integrity asserts that a privacy violation has occurred when either contextual norms of appropriateness or norms of flow have been breached” (125).

In terms of The Data Dollar Store, the contextual norms of appropriateness or flow have not been breached since the subjects involved personally chose to share their personal data in return for a product and piece of art. Nissenbaum in this sense, directs the concept of privacy as contextual integrity to the data and information flows that are shared on online platforms. The platforms collect the data and subsequently, invisibly share or sell this information to second or third parties. According to Nissenbaum these practices are a breach of privacy since users have not given permission for these actions. So, at first sight The Data Dollar Store seems rather transparent in the way they deal with personal data, as it is a form of transaction: a couple of photos for a product, but then again, what happens to the data that has been handed over? Where is it stored? Does it mean then that the personal data that has been handed over is of temporary value, unless it is stored and reused again for the company’s gain?

Surveillance

This leads to another view of privacy and surveillance. Jeremy Bentham who introduced the term “panopticon” in the 18th century introduced a theory and method of how surveillance can work. The panopticon is an architectural design that can monitor prisoners without them knowing whether or not they are being monitored. It can be seen as a central viewpoint looking at the circular periphery as well as meaning to assert a certain power to the ones that are being watched. This type of monitoring and surveilling can also be used in the contemporary context of the internet. As Susan Barnes states: “Internet software can be used as a para-societal mechanism for the observation of online interactions”. These online interactions via social media can be seen and experienced as private interactions, but in reality are public journals and diaries (Barnes). The boundary between the online private sphere and online public sphere continues to be vague and undefined for the user making it easier for the platform holders to decide how these interactions should take place. By continued vagueness it gives the platform holders the power to continue trading user’s data.

However, the awareness of this grey space between public and private is increasing, causing several initiatives to develop and create an alternative to the centralised system that defines the normative use of the internet today. An example of these initiatives are: Dyne.org who advocate for a free digital community founded on free and open software, Myshadow.org who offer a transparent view of what is happening with your data whilst you are browsing the internet, and the Institute of Human Obsolescence who research what it means to be a “data labourer” as well as setting up a Data Workers Union where they “explore the potential of human-generated data to produce capital for the workers” (Speculative.capital). These examples can be seen as reactions to the monopolized power of the internet as they offer different possibilities of online infrastructure, Kaspersky in this sense fits in with their cyber security software products.

In conclusion, The Data Dollar website states: “Your data is valuable. Just like art. Protect it” (Datadollarstore.com). Which is quite an understandable claim as it is comparing personal online data to the creation of art, meaning that every person is an artist and producer of some sorts and that this shouldn’t be taken advantage of. As James Moor says: “privacy offers us protection against harm” (Moore 28), this is exactly what Kaspersky Lab is trying to say by initiating the Data Dollar Store, it is better to stay protected through their services since they have been “saving the world for 20 years”!

https://www.kaspersky.com/

Bibliography:

Bach, Natasha. “This Pop-Up Shop Only Accepts Your Personal Data as Payment.” The Store That Takes Personal Data as Payment | Fortune.com. Fortune, 08 Sept. 2017. Web. 20 Sept. 2017. <http://fortune.com/2017/09/08/data-dollar-store-takes-personal-data-as-payment/>.

Barnes, Susan B. “A Privacy Paradox: Social networking in the United States.” First Monday. N.p., 4 Sept. 2006. Web. 20 Sept. 2017. <http://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/1394/1312/>.

“Digital Community and Free Software Foundry.” Dyne.org. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Sept. 2017. <http://www.dyne.org/>.

Hatmaker, Taylor. “U.S. Senate votes to oust Russian security software vendor Kaspersky from federal use.”TechCrunch. TechCrunch, 18 Sept. 2017. Web. 20 Sept. 2017. <https://techcrunch.com/2017/09/18/senate-kaspersky-shaheen-ndaa/>.

Henley, Jon. “Ben Eine: the street artist who’s made it to the White House.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 21 July 2010. Web. 20 Sept. 2017. <https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2010/jul/21/ben-eine-artist-cameron-obama/>.

Kaspersky Lab. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Sept. 2017. <http://www.kaspersky.com/>.

“Me and my Shadow.” Home | Me and my Shadow. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Sept. 2017. <https://myshadow.org/>.

Moor, James H. “Towards a Theory of Privacy in the Information Age.” Computers and Society (September 1997): 27-32. University of Ottowa. Web. 24 Sept. 2017. <http://www.site.uottawa.ca/~stan/csi2911/moor2.pdf/>.

Nissenbaum, Helen. “Privacy as Contextual Integrity.” Washington Law Review 79 (2004): 101-39. Kent Law. Web. 22 Sept. 2017. <http://www.kentlaw.edu/faculty/rwarner/classes/internetlaw/2011/materials/nissenbaum_norms.pdf/>.

Obsolescence, Institute Of Human. “Humans are becoming Obsolete.” Institute of Human Obsolescence. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Sept. 2017. <http://www.speculative.capital/>.

Staff, Wired. “Security News This Week: Feds Give Kaspersky Security Products the Boot.” Wired. Conde Nast, 18 Sept. 2017. Web. 20 Sept. 2017. <https://www.wired.com/story/kaspersky-security-news/>.

Summers, Nick. “Inside the store that only accepts personal data as currency.” Engadget. N.p., 08 Sept. 2017. Web. 20 Sept. 2017. <https://www.engadget.com/2017/09/07/data-dollar-store-london-ben-eine/>.

The Data Dollar Store. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Sept. 2017. <http://www.datadollarstore.com/>.