“ToScan”: Media Literacy and Understanding of Terms of Service

We are posing the question “how can we operationalise a form of privacy literacy in order to better understand social media terms of service?” In this research we engage in an academic debate and as an end result propose the creation of an app we named “ToScan” (“Terms of Service Scanner”) which aims to bring transparency to the Terms of Service (ToS) of various Social Network Sites (SNSs).

Introduction

As popular sites such as Facebook and Twitter continue to permeate our digital lives, an ever increasing amount of social activity is moving to SNSs, which have been defined as online services where users create profiles, make connections with other users, and browse through media shared amongst said profiles (boyd and Ellison). SNSs are powerful as they enable users to digitally engage in social activities and share personal content (Hanna et al. 265-266). This power, however, also comes paired with intense responsibility: user conduct, no matter how personal it seems, is taking place in a structured, corporate-owned environment where opportunities for misuse, co-optation and misappropriation are constant. The understanding of these back-end phenomenons is our research focus, centered around the research question: how can we operationalise a form of privacy literacy in order to better understand social media terms of service?

Debate

The term media literacy has an entrenched history of use by scholars. Aufderheide has defined this concept as: ‘’the ability of a citizen to access, analyse, and produce information for specific outcomes’’ (Aufderheide 6-7). According to Hobbs, media literacy is “the ability to access, analyse, evaluate and communicate messages in a variety of forms” (16). Both view media literacy as an understanding of how to critically use media. Potter reviewed literature on media literacy definitions, focusing mainly on the production of content, personal enrichment and opportunities. He concludes: ‘’the definition is limited to skills and ignores knowledge as a foundation for media literature” (430).

Teurlings also problematizes the notion of ‘narrow’ media literacy. His focus on media literacy is not about personally working in the field of media, but about understanding how media are produced. He argues that media have become more transparent about production, but he also critiques this notion:

We need to stress that the transparency of contemporary capitalism is limited to questions of modus operandi: how do they make it? Who is involved and what does each of them do? But conspicuously absent from such ‘mechanic’ descriptions are questions of political economy (524-525).

This emphasizes the lack of understanding about the back-end of media production. Here we argue that a consumer is thus not truly media literate. Understanding media is not only about the ability to access, analyse, evaluate and communicate messages. The political economic aspects of media use are also part of media literacy, and should also be made transparent.

The map of media literacy initiatives published by the European Audiovisual Observatory clearly shows the vast attention paid to promoting media literacy in Europe, which is now been implemented in government policies, as well as widely addressed by the NGO sector. Around the world, the issue has been highlighted by Common Sense Media, the Center for Media Literacy and the National Association for Media Literacy Education (NAMLE), among others. Even though policies are implemented and media literacy is increasingly added to school curriculum, a Stanford study (Wineberg et al.) highlights the inability of students to analyse media.

Whereas the previous definitions focus on traditional media, it is interesting to see if the same applies to digital media. Livingstone focuses on this new form of literacy, “uneasily termed computer literacy or internet literacy” (3). She uses the term media literacy to study how consumers can develop an understanding of how to use digital media, thus focusing on the frontend of media platforms. This argument also applies to Hartley’s book, where he connects media literacy to increasing democratic possibilities. Magolis and Briggs offer a more critical approach towards digital media literacy, arguing: “students make use of privacy settings; therefore, a concern about their privacy must exist” (24). From this perspective it is important for users to receive new media literacy education “to help discern what information is acceptable on SNS’s” (32). They focus not only on the production of our own content in a digital field, but also on privacy issues (Teurling’s questions of political economy). Citing Potter, they argue that media literacy must be developed, and that it requires effort from each individual as well as guidance from experts (32). Here is our research interest, as we explore how to make users aware of the political economy perspectives of digital media, which leads to privacy issues that concern us all.

It is here that we can introduce the term ‘’privacy literacy’’ as a vital concept in the social media era. We consider it of grave importance in our current SNS-enabled social world. Our project aims to join the privacy literacy academic debate, focusing on SNSs in particular, given their aforementioned significance and growing impact: today “1 in every 3 minutes spent online is devoted to social networking and messaging” (Mander and McGrath 5). Users with privacy literacy have an informed concern about their privacy rights and therefore follow an effective strategy to protect these rights (Debatin 50).

At first glance, it may appear challenging for users to achieve a satisfying level of privacy literacy, given the technical complexities of SNSs. This is one of the reasons why SNSs offer users their Terms of Service (ToS): they explain the legal terms on which they are using a social network. ToSs typically include a privacy section, sometimes referred to as “privacy policies.” In addition, researchers have continually shown an interest in how particular ToSs can help shape user behavior. For example, studies have related policy understandings to users’ ability to control behavior online (Park 226). The better understanding users have, the more users tried to protect their information, stressing the importance of fully understanding the ToS.

It can be difficult, however, for users to fully comprehend the ToS. First there is the difficulty of users not (completely) reading the document. According to Steinfeld, the ToS are too complex and long, full of legal and vague language, with small font size and difficult formatting (993). Tsai also wrote about privacy information online, arguing:

In principle, privacy policies fill the information gap between the consumer and the vendor by providing a complete picture of the vendor’s information practices. In practice, however, perusing privacy policies has its share of transaction costs (246).

She goes as far as suggesting that businesses should use information technology tools to explain their policies for a business advantage (255). Our research draws on this suggestion, by conceptualizing it and putting it into practice. We here take Facebook as an SNS example. One method to control personal information on Facebook is to accurately set privacy settings according to one’s privacy preferences. Yabing et al studied this process, where they found Facebook privacy settings only matched users preferences 40% of the time. Thus, even though ToSs are expected to explain and clarify, users often lack the practical knowledge and awareness to ensure their own privacy. We thus argue users need assistance through increased understanding, not only in relation to privacy settings, but also to more broadly protect their ‘’free floating private information’’ against future misuse (Debatin 57).

Different attempts have been made to improve users’ privacy literacy. For example, the Platform for Privacy Preferences (P3P) affords websites to standardise the format of their ToS so that they can be automatically decoded and defined by user agents. The problem with this intervention is that users are not encouraged to increase privacy literacy by engaging in ToS, but rather the opposite: ‘’thus users need not read the privacy policies at every site they visit’’ (Cranor and Wenning). Furthermore, this intervention is situated on a website, far from the use of mobile applications.

Learn more at ToScan.nl

We argue the distance between the intervention and the space of action is too large. Additionally, this project ran strictly on input by websites (P3P). The lack of user’s’ effort for input prohibits meaningful promotion of privacy literacy, as they do not proactively engage in the process of informing themselves (Potter 57). Another intervention, named TosDR does rely on user’s input to classify ToS. However, this classification system can be very specific to a user’s personal interpretation, and users again need to go to a web browser to use this service. Another point worth discussing is the fact that Facebook did an attempt to initiate feedback from users on their policy but there was not enough interest by the users. This confirms the findings discussed in the literature that users find ToS boring and don’t pay enough attention to them which results in their media illiteracy when it comes to privacy.

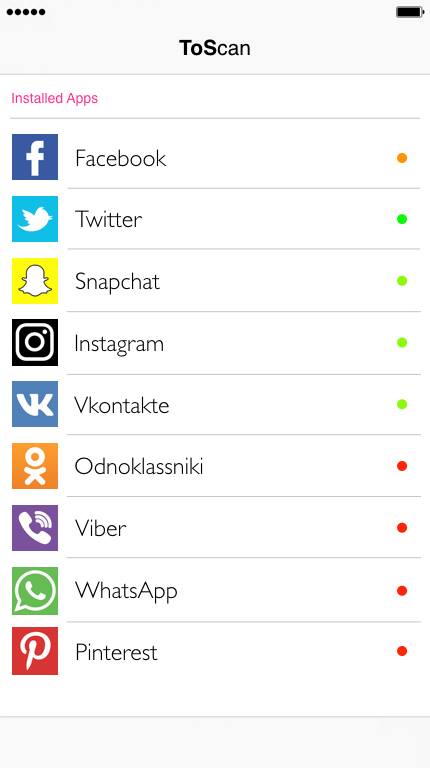

Facebook is accessed via mobile by 90% of its daily active users (Lopez). The absence of a mobile-based ToS interface facilitates the urgency for a new intervention, one truly accessible from mobile devices. Currently, users are asked if they will permit a certain app to have access to their smartphone hardware and software (including camera and GPS) and if they agree to the ToS. However, users tend not to realize what kind of data they share and the impact of their actions. Thus, the true need for our intervention.

Methodology

In order to concretely realize our goal of meaningful intervention in the privacy literacy debate, our methodological approach will be a content analysis of Facebook’s ToS. By analyzing ToS, we will be better able to critically discuss the various ways in which increased user literacy and transparency is needed in the daily use of SNSs. As the constraints of time and space do not allow an analysis of every SNS ToS, we have chosen Facebook, as it is by far one of the most popular SNSs internationally (Constine).

Content Analysis

Learn more at ToScan.nl

Departing from the regular logic of a content analysis, which generally mandates that coded/categorised findings can be used to extrapolate broader trends, our analysis of Facebook’s ToS is more oriented towards better understanding points of concern strictly from a privacy literacy perspective. Thus, we are not attempting to produce a broad, all-encompassing understanding, but rather one that is narrow, focused and of practical use for the end user.

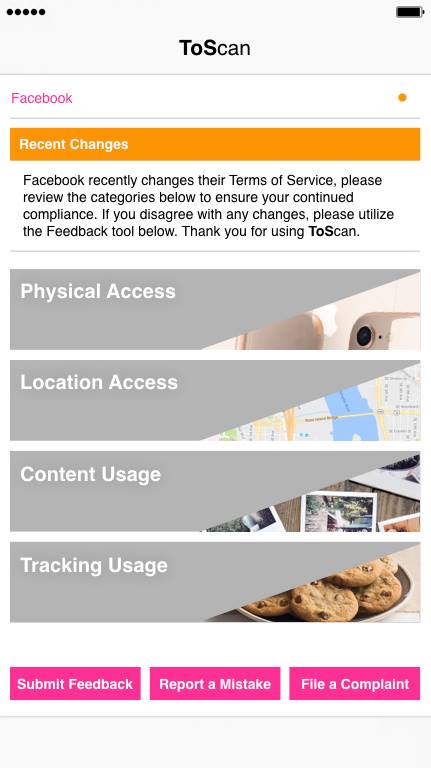

Taking up this mandate, we approached Facebook’s ToS within the lens of four focused categories:

Physical Access: Any terms which enable Facebook to access the camera, microphone, or any other physical electronic equipment contained in a mobile device.

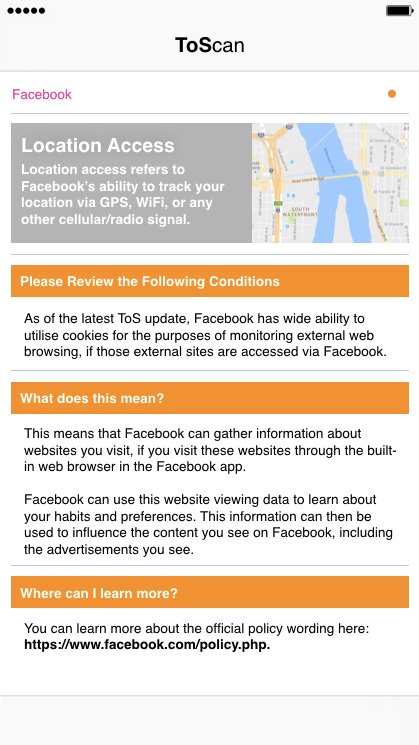

Location Access: Any terms which enable Facebook to access location based information, (including via GPS, WiFi, or cellular network).

Content Usage: Any terms which enable Facebook to reuse uploaded photos, videos, or any other media, for commercial purposes.

Tracking Usage: Any terms which enable Facebook to monitor or track web browsing activity which takes place either within, or external to, the mobile app .

Reading the entire ToS (which is comprised of three documents: “Statement of Rights and Responsibilities,” “Data Policy,” and “Community Standards”) through this categorical lens allowed us to extrapolate the following findings which are divided into two categories: status (indicating what the ToS allows Facebook to do), and evidence (indicating what specific terms allow this activity). *

Physical Access

Status: Facebook does not have the ability to access a device camera or microphone, unless these features are specifically in use by the user.

Evidence: No permitting language found in the ToS, as well as direct confirmation from Facebook (Facebook Newsroom).

Location Access

Status: Facebook has full ability to collect location information at all times.

Learn more at ToScan.nl

Evidence: Data Policy Chapter 1, Section 2, Point 2, indicating Facebook collects “device locations, including specific geographic locations, such as through GPS, Bluetooth, or WiFi signals.”

Tracking Usage

Status: Facebook has wide ability to utilise cookies for the purposes of monitoring external web browsing, if those external sites are accessed via Facebook.

Evidence: Data Policy Chapter 1, Section 6, indicating Facebook collects “information when you visit or use third-party websites and apps that use our Services.”

Content Usage

Status: Facebook has full, non-exclusive ownership of any photos, videos or media that are uploaded.

Evidence: Statement of Rights and Responsibilities, Chapter 2, Section 2, indicating Facebook is granted “a non-exclusive, transferable, sub-licensable, royalty-free, worldwide license to use any IP content that you post on or in connection with Facebook.”

Conclusion

Privacy literacy tends to be neglected by users for various reasons, such as complexity, but it is a crucial part of our SNS experience and thus demands our attention and engagement.

The issue has already been acknowledged and tackled by actors in the public sphere. However, a user-focused intervention is needed for raising awareness about privacy literacy.

Learn more at ToScan.nl

By engaging in an academic discussion and conducting a content analysis of the ToS of one SNS, we defined the concept of privacy literacy, identified the key issues around it and suggested an intervention based on our analysis. We argued that a new interface is needed in order to better understand social media terms of service.

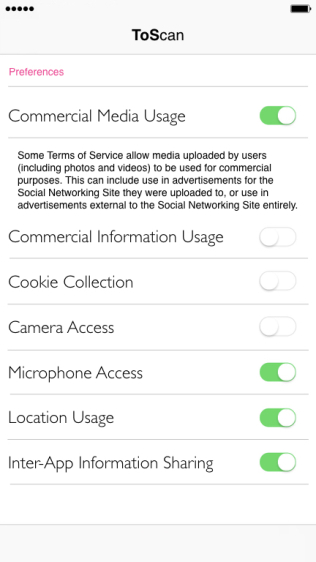

As a manifestation of this research, we propose the creation of ‘ToScan’ (ToScan.nl): a mobile-based ToS scanner which translates the long and legal ToS into user-friendly, easy to understand and interactive ToS app.

* In reaching these findings, we interpreted clauses in the most exhaustive sense possible. As such, we assumed the worst case scenario. Critics could argue that just because Facebook legally can (according to their ToS) partake in such activities, does not necessarily mean they will. While this is true, our goal of promoting privacy literacy demands us to take literally Facebook’s policies, regardless of whether or not they are being acted on at this precise moment.

Bibliography

Aufderheide, Patricia. Media Literacy. A Report of the National Leadership Conference on Media Literacy. Washington, DC: Aspen Institute, Communications and Society Program. <https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED365294>. 2 October 2017.

boyd, Danah M., and Nicole B. Ellison. “Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship”. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 13.1(October 2007): 210–30. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x

Constine, J. “Facebook now has 2 billion monthly users… and responsibility.” TechCrunch. 27 June 2017. 6 October 2017. https://techcrunch.com/2017/06/27/facebook-2-billion-users/

Debatin, Bernhard. “Ethics, Privacy, and Self-Restraint in Social Networking”. Privacy Online (2011): 47–60. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-21521-6_5

Facebook Newsroom. “Facebook Does Not Use Your Phone’s Microphone for Ads or News Feed Stories.” Facebook. 6 June 2016. 20 October 2017.

Hanna, R., A. Rohm and V. Crittenden. “We’re all connected: The Power of the Social Media Ecosystem.” Business Horizons 54.3 (2011): 265-273. doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2011.01.007

Hartley, John. The Uses of Digital Literacy. Transaction Publishers, 2010. Review of The Uses of Digital Literacy, by John Hartley. Contemporary Sociology 40.2 (2011): 243. <http://jstor.org/stable/23042172>

Hobbs, Renee. “The seven great debates in the media literacy movement.” Journal of Communication 48.1 (1998): 16-32. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1998.tb02734.x

Livingstone, Sonia. “Media literacy and the challenge of new information and communication technologies.” The Communication Review 7.1 (2004): 3-14. doi:10.1080/10714420490280152

Lopez, Napier. “90% of Facebook’s daily active users access it via mobile.’’ The Next Web. 27 January 2016. 20 October 2017. <https://thenextweb.com/facebook/2016/01/27/90-of-facebooks-daily-and-monthly-active-users-access-it-via-mobile/>

Magolis, David, and Audra Briggs. “A Phenomenological Investigation of Social Networking Site Privacy Awareness through a Media Literacy Lens.” Journal of Media Literacy Education 8.2 (2016): 22-34. <http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/jmle/vol8/iss2/2>

Park, Yong Jin. “Digital Literacy and Privacy Behavior Online”. Communication Research 40.2 (2013): 215–236. doi:10.1177/0093650211418338

Potter, W. James. “Review of literature on media literacy.” Sociology Compass 7.6 (2013): 417-435. doi:10.1111/soc4.12041

Steinfeld, Nili. ““I agree to the terms and conditions”: (How) do users read privacy policies online? An eye-tracking experiment.” Computers in Human Behavior 55 (2016): 992-1000. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.038

Teurlings, Jan. “From the society of the spectacle to the society of the machinery: Mutations in popular culture 1960s–2000s.” European Journal of Communication 28.5 (2013): 514-526. doi:10.1177/0267323113494077