Growing up on YouTube – How family vloggers are establishing their children’s digital footprints for them

The internet knows what you shared on Facebook last week. It sees what video you posted on YouTube. It even knows you’re reading this blog post right now. Every action you make online creates a trail of data or a digital footprint. Weaver and Gahegan define the term digital footprint as “the digital traces each one of us leaves behind as we conduct our lives” (324). We as adults have a semblance of control over the personal information we share online. We are responsible for the consequences sharing personal information has on our privacy. However, for children who are currently being raised in this era of increasing online presence, their involvement in determining their own digital footprint is limited. Before a child has the chance to establish their own online identity, parents and loved ones may choose to create a digital footprint on their behalf (Leaver 2015, 149). This growing practice of parents uploading content about their children is known as “sharenting”. Legal professor Stacy Steinberg defines “sharenting” as “the ways many parents share details about their children’s lives online” (842).

So what?

According to a 2010 study conducted by Internet security company AVG, 81% of mothers with children under the age of two have uploaded images of their child online. 5% of mothers created a social media profile for their newborn child. Additionally, 23% of mothers uploaded photos of their children’s prenatal scans online, creating a digital footprint for their child before they were even born (AVG). A glance at these numbers indicates a growing trend in the practice of “sharenting,” worthy of further study (Brosch 226). With the development of new platforms and new ways to share, one can only assume that these statistics have increased in the past seven years.

The emergence of new social media platforms allows parents to “sharent” in different ways, ranging from blog entries to daily video blogs (“vlogs”). Family vlogging in particular has given parents a way to publicize the day-to-day happenings in the lives of their children and their family. With some children’s lives being vlogged from the moment they are born, thus before they are able to understand the impact their online presence has, it raises questions about the long-term impacts on their digital footprint.

In the context of the development of this issue in new media studies, our query for research is as follows: How are family vloggers establishing their children’s digital footprint for them?

Foundations of Understanding

The impact of family vlogging on the children involved is still a fairly new area of study, and there are various academic approaches that shine a light on this phenomenon. However, this work has yet to be completed in true definition because the effects of it are just beginning to be recorded. Impact cannot truly be understood until the control of the digital footprints switch possession from the parents to the children as the child comes of age. The lines of theory that we will highlight are only the beginnings of academic study into this area. Therefore, our attempt to synthesize and extrapolate upon these theories as a part of our own research project is similarly just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to this line of inquiry.

Alicia Blum-Ross and Sonia Livingstone offer an approach from the field of communication analyzing parent bloggers specifically. Through their qualitative research they find that many parents view sharenting as a natural extension of previous record-keeping practices when it came to their children’s milestones. The more public nature of the content takes the backseat to the memory storage capacity of the platform (Blum-Ross and Livingstone 115).

In another article, Blum-Ross states, “other bloggers have told me how they find it difficult to figure out where the child’s ‘identity ends and yours begins’ and therefore whether what they post is theirs to share, or their children’s to keep” (2). This is particularly relevant in regard to the definition of the digital footprint and who has the rights to create and edit one for an individual. This is additionally complicated by the introduction of commercial interests, as it is in many cases with family vloggers.

In relation to this theme, anthropologist Crystal Abidin focuses on family video bloggers on YouTube who generate an income from their online content. She references Senft who first coined the term “micro-celebrity” as a person who attempts to gain popularity through online media (Abidin 1). Abidin takes his definition a step further by creating her own subcategory of this definition, namely the “micro-micro-celebrity,” meaning children who will inherit the digital footprints their parents created for them (1). The concept of the “micro-micro-celebrity” pulls focus onto the economic aspect of creating digital footprints and the child’s agency in the process.

A predominant voice in matters of agency in terms of online identity is Australian professor Tama Leaver. As “micro-micro-celebrities” are typically “promoted by their parents” (Leaver 2017), children’s rights to decide on whether or not to participate are easily overlooked. Moving away from Abidin, Leaver discusses the future of these digital footprints pointing out that, “the question of agency or control becomes even more important when the legacy or history of that identity may be entirely inescapable” (2015, 151). Even though Leaver’s take can be interpreted as pessimism, he raises valuable points about the consolidation of data as it pertains to a person’s digital footprint.

Methodology

To approach how family vloggers are establishing their children’s digital footprint for them we decided to apply a multifaceted research strategy. Apart from conducting a text based analysis of relevant academic literature in order to create a theoretical framework, we decided to focus on a specific example of a vlogging family; the SacconeJolys.

With a YouTube following of 1.8 million subscribers and almost 700.000 views, the Saccone-Jolys have reached the status of “Internet superstars” in the family vlogging scene (Molony). The family consists of parents Jonathan and Anna, their three children Emilia (5), Eduardo (3) and Alessia (6 months) and their six maltese dogs. They have been vlogging for six years, documenting everything from major life milestones including their wedding and the births of their children to everyday life. This means that for the past six years, a snippet of each day of the children’s lives has been documented and shared online, making them a valuable example.

After gaining insight into how the Saccone-Jolys structure their vlogs around their children, we conducted a data analysis aiming at illustrating the scope of their children’s data footprint.

We identified three queries that we considered essential to our research objective: The amount of posts the parents have shared on their public social media accounts, the amount of followers they have on their public social media accounts and lastly, the number of search results of their children’s names on different social media platforms, as well as on Google.

We decided to focus on YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram because they are the main social media channels used by the parents to share content about their children (SacconeJolys). Not only did we look at the official SacconeJolys family platforms, but we also included Jonathan and Anna’s individual social media profiles, as they feature the children as well, adding to their digital footprint. This was done with the limitation in mind that there is probably overlap of data, content and reach due to similar fan bases.

Even though Anna and Jonathan each own a Google plus account, as well as having a family one (SacconeJolys), we decided to forego examining them, as they have either been out of use since 2015 (SacconeJolys), 2013 (Jonathan Joly), or only generate automatic (blog) updates anymore (Anna Saccone).

We gathered all data on October 16, consulting the individual social media accounts, as well as using the platforms’ embedded search function.

Starting out with looking at the amounts of posts shared by the parents, we retrieved the latest numbers from the relevant social media platforms, these being YouTube (SacconeJolys, FriendliestFriends, AnnaSaccone and JonathanJoly), Instagram (@annasaccone and @jonathanjoly) and Twitter (@annasaccone and @jonathanjoly). Due to Facebook’s restrictions in accessing a certain page’s number of posts, we were not able to include the amount of Facebook posts published by Anna and Jonathan in our findings.

Our next step was to note the amount of followers the family, as well as the parents’ platforms have. We did so by obtaining figures from the relevant social media platforms, these being YouTube (SacconeJolys, FriendliestFriends, AnnaSaccone and JonathanJoly), Instagram (@annasaccone and @jonathanjoly), Twitter (@annasaccone and @jonathanjoly) and the parents’ official Facebook pages (Anna Saccone and Jonathan Saccone Joly).

Finally, we collected the number of results using the hashtag mentions #emiliasacconejoly, #eduardosacconejoly and #alessiasacconejoly on the social media platforms Instagram and Twitter and we searched the children’s full names on YouTube, using the platform’s own search bar. We added Google as a resource due to its status as the pre-eminent search engine on the web (Krawczyk), using “Emilia Saccone Joly”, “Eduardo Saccone Joly” and “Alessia Saccone Joly” as keywords. Because of Facebook’s restricted access to an exact number of available search queries regarding mentions, we were unable to include these in our findings.

We decided to use table diagrams to visualize our findings as they allow a structured overview and make numbers easily comparable.

Findings

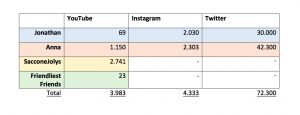

Table A: Number of posts/videos on the respective social media platforms, October 16

Table A shows the amount of information uploaded online by Anna and Jonathan Saccone-Joly, using different social media platforms and different media formats such as YouTube videos, photos, and tweets. Even though not all of the content is specifically centered on their children, the numbers paint a picture of the sheer amount of data that is shared through their public social media channels.

We can think of these findings as the point of origin for a lot of the data that can be farmed about the Saccone-Joly children. These are the very beginnings of their online identity. Even at the onset, there is a wealth of information that can be attained simply from these primary source uploads.

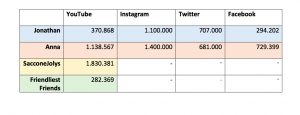

Table B: Followers on the respective social media platform, October 16

Table B shows how many people follow the Saccone-Joly family on the parents’ individual social media platforms as well as the family’s two YouTube accounts, giving an idea of how many people have access to information posted about the children. Drawing from this information, we can see a high level of engagement with the Saccone-Joly family online. These types of large-scale numbers allow us an insight into the family’s audience size, indicating the reach of their content.

Table C: Search results for the children’s names, October 16

Table C shows the number of results when each child’s name is searched on Google, YouTube and Instagram. These figures are indicative of a more active form of engagement with the Saccone-Joly children beyond of what their parents share. While the numbers seem respective of the children’s ages, we can estimate an exponential growth pattern based on the popularity of the younger children’s search results.

The Future of Sharenting Studies

Even though we were able to collect large amounts of data, we were clearly limited in our scope and capability to extract this data. As we previously mentioned, these results serve as a natural springboard into more exhaustive studies into this topic. We have moved from a theoretical perspective on how parents affect and dictate the digital identities or footprints of their children to a larger understanding of the ripple effect of posting content about children online.

We set out in this research endeavor to discover how family vloggers were establishing their children’s digital footprint on their behalf. Our findings were much more far-reaching. Namely, it is not just the parents who create and have control of their child’s digital footprint. Once the content has been released by the parents, it now belongs in the public domain. We have seen how content improvisation occurs based on the data that the parents decide to share. Just as the children unknowingly surrender the rights of their digital footprint to their parents, the parents are also surrendering those same rights to the public once the data is published. The reach of the digital footprint doesn’t end at the parents’ fingertips. In fact, as we have illustrated through our findings, the reach is ever-changing and hard to quantify in a meaningful way.

Leaver describes this phenomenon by creating his own definition of content improvisation by outsiders. He outlines this as, “digital shadows, which, whether benignly or maliciously, are about, but not in the control of, a specific individual” (Leaver, 2015, 150). The “digital shadows” can often surpass the size of the original digital footprint. By the time children come of age to take responsibility of their online identities, they may be staggered by the influence of their digital footprint.

Surely, the Saccone-Joly children will have their own input on this once they grow up and their understanding increases. Once they desire to start controlling their own digital footprint, they will have to reconcile this new data with all the previous data that exists about them online. The “digital shadows” through which they will have to navigate will be immense before they reach the legal age of adulthood.

Bibliography

Abidin, Crystal. “Microcelebrity: Branding Babies on the Internet.” Media/Culture Journal [Online], 18(5) (2015):1-12. Web. 7 October 2017.

AVG. “Digital Birth: Welcome to the Online World.” Web. 2010. 7 October 2017. <http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20101006006722/en/Digital-Birth-Online-World>

Blum-Ross, Alicia and Livingstone, Sonia. “‘Sharenting,’ parent blogging, and the boundaries of the digital self.” Popular Communication. 15(2) (2017): 110-125. Taylor & Francis. Web. 7 October 2017.

Blum-Ross, Alicia. “‘Sharenting:’ Parent bloggers and managing children’s digital footprints.” London School of Economics Blog. 2015. 18 October 2017. <http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/parenting4digitalfuture/2015/06/17/managing-your-childs-digital-footprint-and-or-parent-bloggers-ahead-of-brit-mums-on-the-20th-of-june/>

Brosch, Anna. (2016). When the Child is Born into the Internet : Sharenting as a Growing Trend among Parents on Facebook. The New Educational Review. 43. 225-235. 10.15804/tner.2016.43.1.19.

Krawczyk, Konrad. “Google is easily the most powerful search engine, but have you heard who’s in second?” Digital Trends. 2014. 18 October 2017. <https://www.digitaltrends.com/web/google-baidu-are-the-worlds-most-popular-search-engines/>

Leaver, Tama. “Born Digital? Presence, Privacy and Intimate Surveillance.” Re-Orientation: Translingual Transcultural Transmedia. Studies in narrative, language, identity, and knowledge. Ed. John Hartley and Weiguo Qu. Shanghai: Fudan University Press, 2015. 149-160. Print.

Leaver, Tama. “When exploiting kids for cash goes wrong on YouTube: The lessons of DaddyOfFive.” 2017. Web. 18 October 2017. <https://www.digitaltrends.com/web/google-baidu-are-the-worlds-most-popular-search-engines/>

Molony, Julia. “’People are obsessed’ – Irish internet superstars the Saccone Jolys on transforming their lives into an empire.” The Irish Independent. 2017. 18 October 2017. <http://www.independent.ie/life/family/family-features/people-are-obsessed-irish-internet-superstars-the-saccone-jolys-on-transforming-their-lives-into-an-empire-35695020.html>

SacconeJolys. 2017. YouTube. Web. 7 October 2017. <https://www.youtube.com/user/LeFloofTV>

Steinberg, Stacy B. “Children’s Privacy in the Age of Social Media.” Emory Law Journal. 66 (2016): 839-884. Hein Online. Web. 7 October 2017.

Weaver, Stephen D. and Gahegan, Mark. “Constructing, visualizing, and analyzing a digital footprint.” Geographical Review. 97(3) (2007): 324-350. Wiley Online Library. Web. 7 October 2017.