Platform Capitalism: Democratic Subjectivity and the Democratic Surround

Drawing on Fred Turner’s book “The Democratic Surround”, this blogpost will dive into what it means and where it originates. The main question of this book is: ‘Was there a mode of communication that could produce more democratic individuals?’

The answers to these questions ultimately produced the ecstatic multimedia utopianism of the 1960s and, through it, much of the multimedia culture we inhabit today.’ (Turner 2014). The book returns to the late 1930’s and early 1940’s to see how and to provide an historical overview.

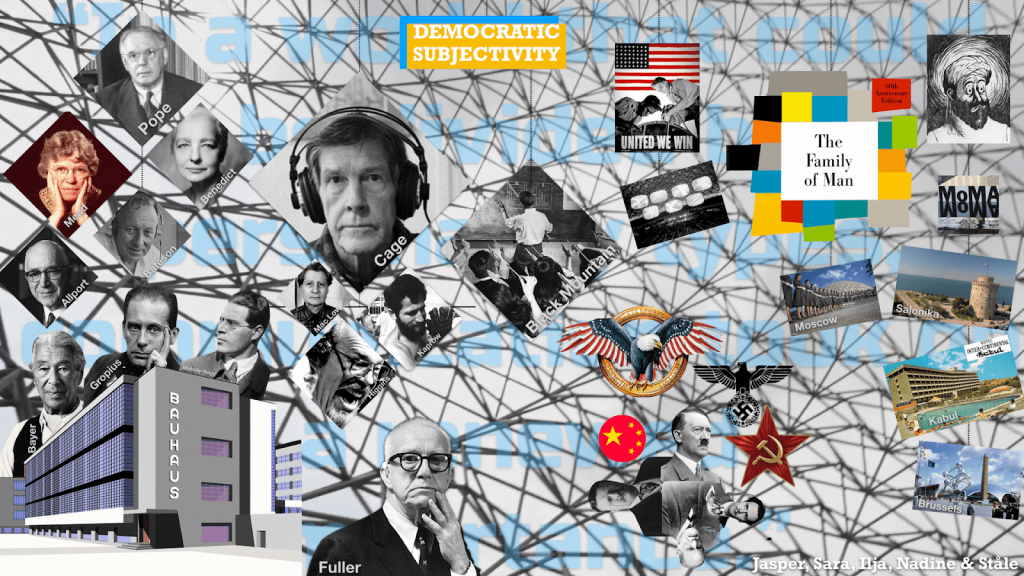

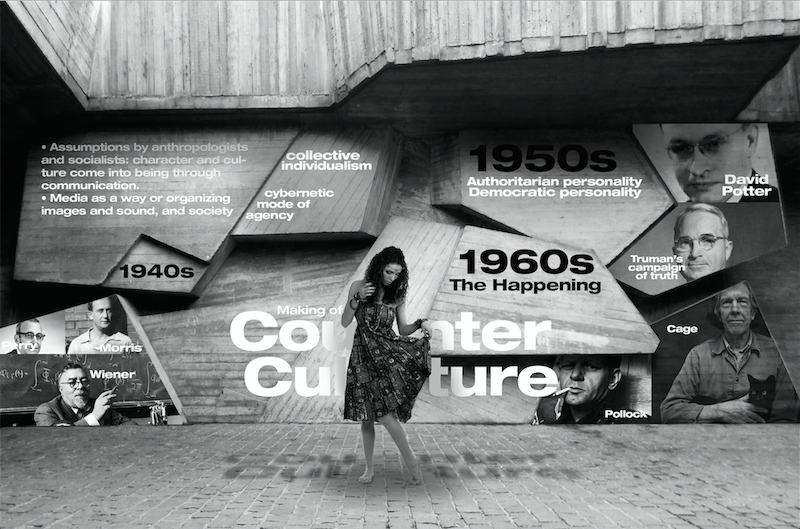

After the second world war the United states saw itself as a nation with a mission – to make sure it was able to defend itself from totalitarianism, from within and out. The US mission was to create a democratic individual and export it to other nations of the world. Those attempts started already during the war, when the committee for national morale, which included major figures such as Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson, defined the “democratic personality” as a highly individuated, rational, and empathetic mindset, committed to racial and religious diversity, and so able to collaborate with others while retaining its individuality.” They believed that both individual character and national culture came into being via the process of communication.

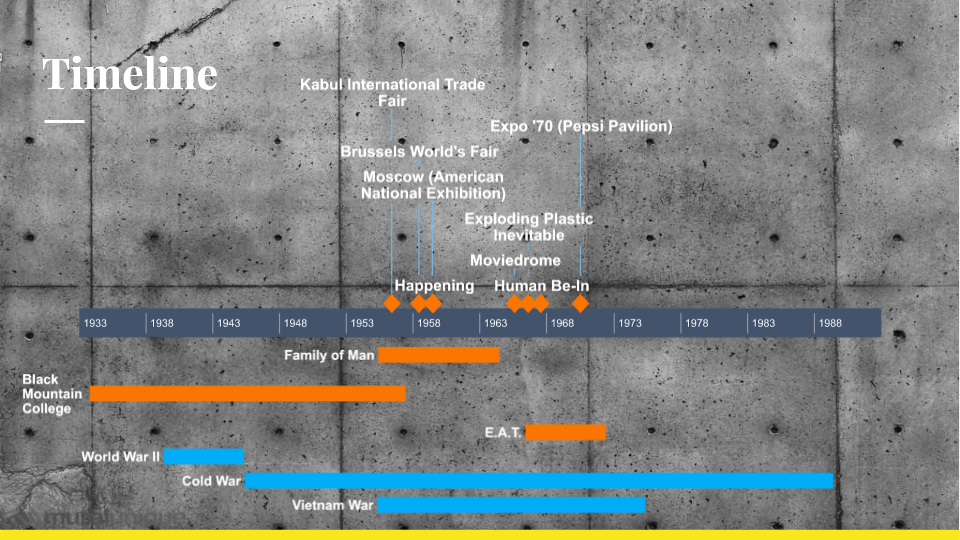

Members and friends of the committee advocated a turn away from single-source mass media and toward multi-image, multi–sound-source media environments – systems that Fred Turner calls surrounds. Collaborating with artists from the Bauhaus movements they started creating exhibitions in the United States during the war. The ideas they sustained later, in the 50’s, during the cold war, turned into propaganda and art that were also displayed in world exhibitions and trade fairs. “The family of man” photography exhibition for example traveled the world, and with it other kinds of surrounds, with the involvement of the USIA – the postwar governmental agency charged with overseas propaganda work.

One of Turner’s overarching claims is that “from the distance of our own time, the surround clearly represented the rise of a managerial mode of a control: a mode in which people might be free to choose their experiences, but only from a menu written by experts.” (p. 15). He also claims that the surround influenced artists such as John Cage and Allan Kaprow, pioneers of the performance art genre, that created a new form of art events, called happenings. The book ends with the synthesis of these ideas – in which Turner argues the American world exhibition pavilions and multimedia surrounds of the 60s counterculture employ similar means to influence individuals and thereby change the world. On a timeline we presented the major case studies of Turner’s book and relate them to bigger events happening at the time such as the Cold War and the Vietnam War.

By Yarden Skop, Els Versluis, Liam Corcoran, Esmee Schoutens