Can we “unplug online”? The Paradox of Meditation Apps and Mindfulness

In our digitized world, people long more and more for taking a step back from social media and the overload of information to focus on their ‘inner self’ and guess what – there’s an app for that! Using the phone against its own negative effects sounds paradox? It certainly does, but the market for wellness related apps is booming and the meditation app Headspace is right ahead.

Source: Headspace

Mindfulness sells

Overall, one could raise the question as to why topics like meditation and mindfulness became new media phenomena in contemporary digital media culture when in fact they originated from 2,500-year-old Buddhist and spiritual traditions. Mindfulness and wellness in general became popular on social media in the last two decades, especially through the constantly rising promotion of yoga and meditation on platforms like Instagram (Cowans 38-40; Mani et al.). ‘Self-tracking’ devices and applications allowing users to monitor their fitness, sleep and eating behaviour are available on the market for several years now. A more recent phenomenon are wellness trackers encouraging the user to slow down to link mental and physical health (Pomputius 178). Mindfulness and meditation apps were stated to be one of four “breakout trends” in app culture in 2017 by Apple editor (Ruiz).

Headspace: Meditation made simple

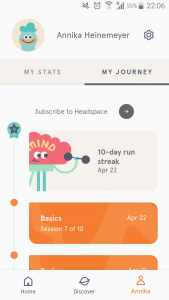

Headspace was launched in May 2010 and is one of the most successful programmes for mindfulness and meditation on the market (Perez und Lunden; Agate). Headspace offers guided meditations spoken by co-founder, former monk and “mindfulness expert” Andi Puddicombe (Headspace). What makes Headspace so special is that it functions based on the methods of gamification. Gamification describes simply said methods of making boring activities fun (Maturo et al. 253). Here: mediation, the process of doing more or less nothing. After downloading the app, users get encouraged to go on a 10-day ‘meditation path’ in which they learn about the fundamental principles of meditation and mindfulness through short animated videos based on science and daily meditation sessions. To keep them on track, Headspace uses so-called ‘game mechanics’ that can come up in form of badges, points or levels (Morozov 203). The app tracks precisely how long and frequently one meditates and monitors the benefits which can be shared online with the app community. After the trial, users can get access to different packs tackling a whole range of themes ranging from anxiety, mindful eating, stress, pregnancy, productivity and even coping with cancer. The length of the meditation is customisable individually and there are even ‘to-go-meditations’ so that everyone can squeeze in a couple of mindful minutes every day (Puddicombe).

Source: Headspace

Mindfulness trough Media?

According to Jon Kabat-Zinn mindfulness means “paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment by moment” (145). A study on the evaluation of mindfulness apps identified 700 apps relating to this topic (Mani et al.). Several findings have linked mindfulness to an overall psychological well-being by reducing distressing emotions like anxiety, depression, fear and over-engagement with thoughts and emotions (Hayes and Feldman 256-257; Keng et al.). In a recent study the effects of smartphone-based mindfulness intervention on people’s well-being was examined by using the app Headspace for 10 days. The results have shown actual positive influences on the participants well-being, if given that they had the intention to seek happiness beforehand (Howells et al. 172).

The Paradox of Mindfulness Apps: Why not simply put the Phone away?

Despite the positive effects Headspace has on people seeking happiness and mindfulness, certain paradoxes coming with it cannot be denied. Findings show that a high use of information and communication devices can be linked to mental health issues like depression, anxiety and an increased stress level (Lleras and Panova; Kuntsman and Miyake). Khalaf states that on average, we check our digital devices every 6.5 minutes, 150 times per day and spend most of our time engaging with mobile applications (qtd. in Howells at al. 164).

An obvious solution to this matter could be to just put the phone away and go on a so-called ‘Digital Detox‘. The question is: Isn’t it ironic that smartphone apps should help us to overcome its own negative impacts? In his work, Pomputius refers to several studies concerned with the negative impacts of wellness technologies: “a constant obsession with wellness can actually hurt health consumers by causing them regular anxiety over a perceived lack of conscious wellness moment to moment and instilling an insidious idea that they must constantly pursue wellness and are not, in fact, already healthy in their current state” (180). Additionally, Morozov makes the point that by letting technologies interfere into our habits, we might lose awareness of why and how we are meditating at all: “You seem to be exercising autonomy while, in reality, you aren’t” (237). Headspace co-founder Andi Puddicombe defends the use of mobile application as part of the concept: “For most of us, the phone is the most stressful thing in our life — and I love the paradox in that, the irony. The phone’s a piece of plastic, a piece of metal, a piece of glass. It’s not good or bad…. We define the relationship with the phone. I love the idea that the phone can actually serve up something really good, that’s good for our health” (qtd. in Rosenberg).

A look into the Future of Mindfulness and Wellness Apps

Considering the rising demand for psychological services as well as the increasing popularity of mindfulness apps, one could raise the question if health mobile application might slowly replace face-to-face-therapy (Mathures). Even if studies have shown actual positive effects of mindfulness apps, the danger of missing the real point of meditation and mindfulness remains. If self-tracking triggers an unhealthy obsession with mindfulness and wellness or if the method of gamification makes a competition out of meditation, the intention to seek for a healthier emotional state -may it be becoming more mindful or focussing more on oneself- fails. If this becomes the case, users may even aggravate the negative impacts on mobile devices they might wanted to take a step back from.

Mindfulness does not mean avoiding digital media, nor does it mean making one’s own mindfulness dependent on it – so let’s be more mindful when it comes to mindfulness!

Sources Cited and Consulted

Agate, Jacqui. “10 best mindfulness apps.” Independent. 19. February 2018. https://www.independent.co.uk/extras/indybest/gadgets-tech/phones-accessories/best-mindfulness-apps-for-anxiety-free-sleep-iphone-top-for-kids-a8217931.html. Accessed 19. September 2018.

Arias, Orlando et al. “Privacy and Security in Internet of Things and Wearable Devices.” IEEE Transaction on Multi-Scale Computing Systems, vol. 1, no. 2, April-June 2015, pp. 99–109. IEEE Xplore Digital Library, doi:10.1109/TMSCS.2015.2498605. Accessed 19. September 2018.

Cowans, Skyler. “Yoga on Instagram: Disseminating or Destroying Traditional Yogic Principles?” Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications, vol. 7, no.1, 2016, pp. 99-109. Elon University, elon.edu/docs/e-web/academics/communications/research/vol7no1/000_Full_Spring_2016_Issue.pdf#page=33. Accessed 18. September 2018.

Hayes, Adele M. and Greg Feldman. Clarifying the Construct of Mindfulness in the Context of Emotion Regulation and the Process of Change in Therapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, vol.11, no.3, 2004, pp. 255-262. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1093/clipsy/bph080. Accessed 19. September 2018.

Headspace, Inc. Headspace. 2018. https://www.headspace.com/. Accessed 16. September 2018.

Howells et al. “Putting the ‘app’ in Happiness: A Randomised Controlled Trial of a Smartphone-Based Mindfulness Intervention to Enhance Wellbeing.” Journal of Happiness Studies, vol. 17, no. 1, 29. October 2014, pp: 163-185. Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht, doi: 10.1007/s10902-014-9589-1. Accessed 22. September 2018.

Kabat-Zinn, Jon. “Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Context: Past, Present, and Future.” Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, vol. 10, no.2, 11. May 2003, pp. 144-156. Wiley Online Library, doi: 10.1093/clipsy. bpg016. Accessed 18. September 2018.

Keng, Shian-Ling et al. “Effects of Mindfulness on Psychological Health: A Review of Empirical Studies.” Clinical psychology review, vol. 31, no. 6, 13. August 2011, pp. 1041–1056. PMC, doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.04.006. Accessed 19. September 2018.

Kuntsman, A. and E. Miyake, E. “Paradoxes of Digital dis/engagement: Final Report.” Working Papers of the Communities & Culture Network, University of Leeds, October 2015 +, vol. 6. White Rose Research Online, http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/114806/. Accessed 19. September 2018.

Lleras, Alejandro and Tavana Panova: Avoidance or boredom: “Negative mental health outcomes associated with use of Information and Communication Technologies depend on users’ motivations.” Computers in Human Behaviour, vol. 58, May 2016, pp. 249-258. Science Direct, doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.12.062. Accessed 19. September 2018.

Mani, Madhavan et al. “Review and Evaluation of Mindfulness-Based iPhone Apps.” Ed. Gunther Eysenbach. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth, vol. 3, no. 3, e82, 2015. PMC, doi: 10.2196/mhealth.4328. Accessed 21. September 2018.

Mathures, Paul. “Pop an app- When the mind wanders or can cope no more, there’s a calming-down session that’s just a click away.” The Telegraph, 26. August 2018, telegraphindia.com/technology/pop-an-app-254566?ref=hm-new-stry&fromNewsdog=1&utm_source=NewsDog&utm_medium=referral. Accessed 19. September 2018.

Maturo, A et al. “An Ambiguous Health Education: The Quantified Self and the Medicalization of the Mental Sphere.” Italian Journal of Sociology of Education, vol. 8, no. 3, 2016, pp. 248- 268. Padova UP, doi: 10.14658/pupj-ijse-2016-3-12. Accessed 20. September 2018.

Morozov, Evgeny. To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism. New York, Public Affairs, 2013.

Mulry, Tania. “Need a Digital Detox?” YouTube, uploaded by TEDx, 27. July 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vx7fVEHZtj0&t=1s.

Perez, Sarah and Ingrid Lunden. “Meditation app Headspace bets on voice and AI with Alpine.AI acquisition.” Techcrunch, techcrunch.com/2018/09/04/meditation-app-headspace-bets-on-voice-and-a-i-with-alpine-ai-acquisition/ Accessed 17 September 2018.

Pomputius, Ariel F. “Mind over Matter: Using Technology to Improve Wellness.” Medical Reference Services Quarterly, vol 37, no. 2, 20. March 2018, pp. 177-183. Taylor & Francis Online, doi: 10.1080/02763869.2018.1439222. Accessed 21. September 2018.

Puddicombe, Andi. “All it takes is 10 mindful minutes.” YouTube, uploaded by TED, 01. January 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qzR62JJCMBQ.

Rosenberg, Scott. “The Unbearable Irony of Meditation Apps.” wired, 30. August 2018, wired.com/story/the-unbearable-irony-of-meditation-apps/. Accessed 19. September 2018.

Ruiz, Rebecca. “Calm yourself – One woman’s quest to find the right meditation app in a messed-up world.” Mashable, mashable.com/2018/02/01/best-meditation-apps-mindfulness/?europe=true#Sfnv_tadcmqy. Accessed 19 September 2018.