IGTV: The Latest Blow to Traditional TV?

On the 20th of June this year, next to an announcement that they now have over a billion monthly active users, Instagram announced the release of Instagram TV – also referred to as IGTV – in a video that was uploaded directly to the new platform (Systrom).

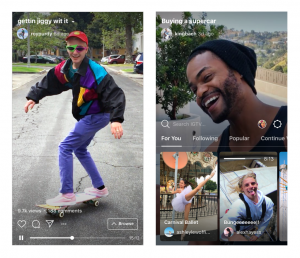

IGTV is a standalone application – which you can get access to directly by clicking on the application itself or by clicking on the IGTV symbol in the main Instagram app. Login in doesn’t require you to have an Instagram account, you can also log in with Facebook. Once you have logged in, a video of one of the accounts you follow starts playing, much like regular TV. While the main app could be said to focus more heavily on the concept of liveness with Instagram stories, IGTV aims to a more polished kind of content to be uploaded to the app; there is no video button, only an upload button, which means that content has to be filmed in advance. Every account creates content and are marketed as channels and every user thus has the opportunity to create, which produces more grassroots content.

IGTV raises questions about what it means to watch TV nowadays. Watching television used to be linked to watching shows and programs on a television set, and was regarded as “society’s most important medium for the communication of information and entertainment,” Inge Ejbye Sørensen reports (385). This has changed due to the era of convergence we are currently living in, an era Henry Jenkins describes as “the flow of content across multiple media platforms, the cooperation between multiple media industries, and the migratory behaviour of media audiences” (3). This means that there are now multiple ways to watch television content, and the traditional television set is only one of them. This means that traditional television has come under threat, as Enli Gunn and Trine Syversen state that “the most disruptive digital intermediaries in regards to linear television are content aggregators such as Netflix, HBO, Amazon and YouTube” (144).

Due to these changes in technology, audience and spectatorship has moved from an passive to an active pastime – giving the audience the power to participate, interact and create on their own terms – resulting in a new type of agency where the consumers can climb into the TV themselves as it were (Jenkins 19; Katz 15; Gunn and Syvertsen 143; Newman and Levine 15). This results in a more social type of television: people can share what they want with who they want whenever they want to, which could pose as a threat to broadcast networks and satellite TV if they do not act upon this (Newman and Levine 1; Gunn and Syvertsen 145; Ejbye Sørensen 381). At the same time, simultaneously watching television has made room for more individual modes of watching TV, thus going from a collectivist to an individualist phase of consuming content (Katz 2; Gunn and Syvertsen 145). Perhaps the reason why television shows try numerous ways to interact with their viewers by means of links to social media, hashtags, voting, and so on is because they know that a passive viewer is something of the past, and that in order to keep your viewers you actually have to interact with them and have them engage with your content.

IGTV, unlike YouTube, Vimeo and other already established video-sharing platforms, is the first of its kind that focusses solely on content shot with your phone, with the aspect ratio being 9:16 instead of 16:9. This means that the videos uploaded to IGTV should all be shot vertically, or you lose the risk of not seeing the sides of your video once uploaded. This is where IGTV really distinguishes itself from already established platforms for video-sharing. The launch of the app did not go without its setbacks, with many people stating confusion on how to use the app as the main problem. As a result of this, many guides on how to use the app have been uploaded to YouTube, which seems ironic, because IGTV also aims to give influencers and content-creators the opportunity to keep everything on the platform instead of having to use YouTube for videos longer than 60 seconds. (Systrom).

IGTV lets you create videos up to 10 minutes and verified accounts or accounts with more than 10.000 followers can even create videos up to 60 minutes. According to co-founder Mike Krieger, creators now get the opportunity to create things that “are more episodic with themes, whether that’s a cooking show or an illustration series” (Buxton). IGTV therefore offers an alternative to television watching where people can interact rather than just consume. It is thus an example of a platform where the distinction between user-generated and professionally produced content is reduced (Gunn and Syvertsen 145). The passiveness of the watcher of regular TV is erased here by means of likes, reactions, the opportunity to create, and so on.

“The very first version [of Instagram TV] we built internally didn’t have comments, and our future aspiring

creators internally were like, this is tending towards the direction that we don’t want to go in, because it

starts feeling really empty on the creator side because you’re putting it out into the void” (Buxton).

Krieger adds that this holds true for the consumer side as well, who, he states, want to feel a certain connection towards people behind the video too (Buxton). IGTV builds further on the notion of participatory culture, a culture in which viewers are active, the barriers to create are relatively low and where the media producers and consumers are not occupying separate roles anymore but meet each other in a space that includes both bottom-up grassroots content and top-down corporate processes (Jenkins 3-18; Jenkins et al. 7). This also means that not everything uploaded to IGTV is of the same quality, which – just like platforms such as YouTube or Vimeo do – raises questions about whether they are worthy to be called TV. Nevertheless, fact remains that audiences are migrating nowadays, and that content should be more specialised and individualised for them, which is exactly what IGTV does.

The question whether the ‘live’ watching of television on a television set can survive the continuous blows that technological innovations that streaming platforms such as Netflix, YouTube, Video-on-Demand and now IGTV have dealt remains to be seen, but fact is that consumers are not here only to consume anymore, they are here to be heard, and their voices are louder than ever.

Works Cited

Buxton, Madeleine. “Welcome to IGTV: An Interview With Instagram’s Co-Founder.” Refinery29, 26 Jun.

2018, https://www.refinery29.com/2018/06/202610/igtv-instagram-tv-video-length-mike-krieger-

interview. Accessed 16 Sep. 2018.

Ejbye Sørensen, Inge. “The Revival of Live TV: Liveness in a Multiplatform Context.” Media, Culture & Society 38.3

(2015): 381-399. Web. 19 Sep. 2018.

Gunn, Enli & Trine Syvertsen. “The End of Television—Again! How TV Is Still Influenced by Cultural Factors in the

Age of Digital Intermediaries.” Media and Communication 4.3 (2016): 142-153. Web. 21 Sep. 2018.

Jenkins, Henry. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press,

2006. Print.

———, Ravi Purushotma, Margaret Weigel, Katie Clinton, and Alice J. Robison. Confronting the Challenges of

Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century. Cambridge: Mit Press, 2009. Print.

Katz, Elihu. “Introduction: The End of Television?” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social

Science, 625 (2009): 6-18. Web. 19 Sep. 2018.

Newman Michael Z. and Elana Levine. Legitimating Television. New York: Routledge, 2012. Print.

Systrom, Kevin. “Welcome to IGTV.” Instagram Press, 20 Jun. 2018,

https://instagrampress.com/blog/2018/06/20/welcome-to-igtv/. Accessed 16 Sep. 2018.