Make-Up Metrics: The Downfall of the Beauty Community on Youtube?

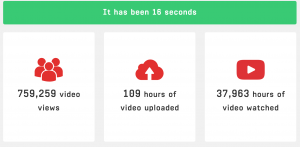

Since its inception in 2005, YouTube has been host to an ever-expanding community of people looking to showcase their artistic and creative ideas on the platform. With over a billion hours of videos watched every day and with tools available to see how many minutes of footage are uploaded to YouTube per second, it goes without saying that YouTube has become a force to be reckoned with: it is a creative outlet and a subsidiary of the enormous global force that is Google Inc., and “since being purchased by Google, YouTube has adopted a new e-commerce model” (Holland, 2012).

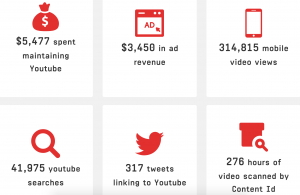

As YouTube’s newest business evolved, so did the beauty community. YouTube’s enormous beauty community is a saturated media space categorised by seemingly surface-level information and news stories of creator’s six-figure bank accounts. In comes SocialBlade.com, a data-aggregating site where one can search any online content creator’s analytics. It shows how “‘excessive’ information can be reduced to a form in which it can be meaningfully, if partially, rendered for interpretation” (Ruppert, 2013).

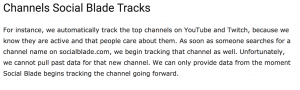

Social Blade markets themselves as “a bit like a journalist” whereby they collect, enter, compile, store and interpret information data (Giltman, 2013). Social Blade aggregates data from across platforms and provides the user of the site with tools to analyse a creator’s statistics. However, after Instagram blocking third-party API software, and YouTube views being sold in the millions, sites like Social Blade, that once could have collected data seamlessly, need to be at the cutting edge of data protection advancements. Unfortunately, data-aggregating sites such as Social Blade create a “sense of starting with data” which “often leads to an unnoticed assumption that data are transparent, that information is self-evident, the fundamental stuff of truth itself” (Giltman, 2013).

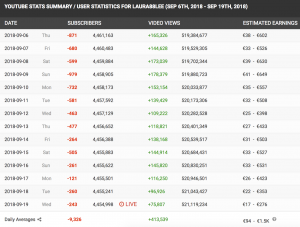

Dutch beauty YouTuber NikkieTutorial’s analytics as aggregated by SocialBlade.com

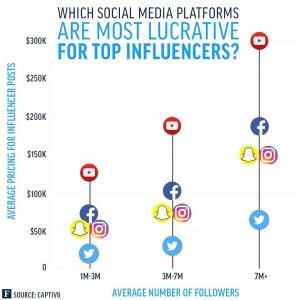

While some claim that sites like Social Blade are a “key tool” for brands, where they can monitor engagement and invest wisely into influencers, we can see the real-world effect of a neoliberal sphere where “competition is the basis of social relations” between influencers (Lemke, 2002). This idea imploded within the beauty community on YouTube this past month, as influencers were outed as charging upwards of $60,000 to feature a particular product. As news of YouTube creators buying views became public knowledge, as well as the EU General Data Protection Regulation sweeping the internet and terms of services were in need of an update, many feel that tools such as Social Blade are essential for “simplifying, summarising, visualising and analysing digital data […] in the context of people, instead of tracking a subject that is reflexive and self-eliciting, they track the doing subject” (Ruppert, 2013).

Screenshot: How Social Blade determines which names to track.

As Kitchin noted, data are “inherently partial, selective and representative” (2014). Now, equipped with tools such as Social Blade, a data analysing app that “gives all users access to our public database which, using advanced technology, is able to provide you with global analytics for any content creator, live streamer, or brand”, it is possible to carve out metrics for anyone present across social media platforms (Socialblade.com). The question then becomes what do these numbers mean in the offline world? It is a point of contingency in the beauty community, where the “influencer” has over time become “human capital” with nearly 45,000 beauty related YouTube channels and the potential to reach millions of viewers (Read, 2009). Tools like Social Blade can enable consumers to project false narratives onto an entire community within YouTube, where data is not collected at a channel’s inception and is not representative of the whole.

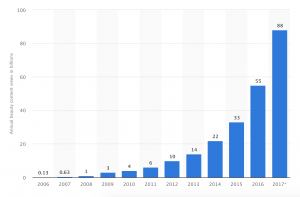

This graphs shows the growth of beauty-related content views per year on YouTube from 2006 – 2017. Source: Statista.com

Ultimately, YouTubers have become more influential than traditional celebrities. Consumers of beauty content are rigorously subjected to lavish videos of hauls, brand trips and sponsorships, so Social Blade is utilised on the basis that “because data stand as a given, they can be taken to construct a model sufficient unto itself: given certain data, certain conclusions may be proven or argued to follow” (Giltman, 2003). Consumers can Therefore, when creators are enthralled in scandals, and the audience becomes fed up of the “fake” personas, they languish statistics, data and personal information across the internet, with the aid of tools such as Social Blade in an attempt to tarnish creators’ reputations.

![]()

Analytics for Laura Lee, a popular YouTuber in the wake of a “beauty community scandal”.

It is worth noting that the viewer and consumer, should think whether they would like their personal net worth speculated across the internet for anyone to see. We must question why consumers feel they are entitled to know the net worth of people who, for the most part, started making videos for fun in their bedrooms, with no idea it would manifest into a world wide phenomenon? What does this say about about how consumers engage with the evolving business model embraced by beauty influencers and how they read, analyse, and contribute to their data? Are real life people being limited to “human capital” whereby their worth is intrinsically linked to their statistics?

Foucault argued that “neoliberalism operates less on actions, directly curtailing them, then on the condition and effects of actions, on the sense of possibility.” This rings true for viewers of beauty channels in which “the fundamentally self-interested individual curtails any collective transformation of the conditions of existence” (Read, 2009). Viewers consume content, expecting creators to purchase products with their money (as the distaste for sponsored content grows) so that the viewer does not have to spend theirs, all the while complaining about the system when the numbers are presented instead of “looking under data to consider their root assumptions” (Giltman, 2003). Should certain statistics be protected? In the realm of online entrepreneurship, it seems that anyone is entitled to know your personal business. It’s hard to imagine that this sort of tool would be paraded as “essential” if it were analysing the work of doctors, lawyers and other offline, “conventional” careers.

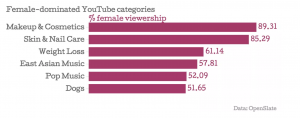

Should influencer’s net worth or statistics be shared? Is it way of increasing transparency in an industry that is saturated in advertisements, sponsorships and brand deals? Or, does it attempt to de-legitimise a female-dominated industry within an already male-dominated realm?

References

Academic Sources

Anarbaeva, Samara M. “Youtubing Difference: Performing Identity In Video Communities”. Journal For Virtual Worlds Research, vol 9, no. 2, 2016. Virtual Worlds Institute, Inc., doi:10.4101/jvwr.v9i2.7193.

Binkley, S., & Capetillo-Ponce, J. (2016). A Foucault for the 21 Century: Governmentality, Biopolitics and Discipline in the New Millennium (pp. 1–398). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Gillman, L. (2003) Raw Data Is An Oxymoron (pp. 1-13).

Holland, M. “How Youtube Developed Into A Successful Platform For User-Generated Content”. Elon Journal Of Undergraduate Research In Communications, vol 7, no. 1, 2018, doi:https://www.elon.edu/u/academics/communications/journal/wp-content/uploads/sites/153/2017/06/06_Margaret_Holland.pdf. Accessed Sept 2018.

Read, J. (2009). A Genealogy of Homo-Economicus: Neoliberalism and the Production of Subjectivity Foucault Studies (pp. 2-15).

Ruppert, Evelyn et al. “Reassembling Social Science Methods: The Challenge Of Digital Devices”. Theory, Culture & Society, vol 30, no. 4, 2013, pp. 22-46. SAGE Publications, doi:10.1177/0263276413484941.

Websites

“Earning Power: Here’s How Much Top Influencers Can Make On Instagram And Youtube”. Forbes.Com, 2017, https://www.forbes.com/sites/clareoconnor/2017/04/10/earning-power-heres-how-much-top-influencers-can-make-on-instagram-and-youtube/#205ccfd324db. Accessed Sept 2018.

“Laura Lee, Jeffree Star, And The Racism Scandal Upending The Youtube Beauty Community, Explained”. Vox, 2018, https://www.vox.com/2018/8/28/17769996/laura-lee-jeffree-star-racism-subscriber-count. Accessed 23 Sept 2018.

“Millennials Are Losing Trust In Online Influencers. Here’S What Marketers Can Do.”. Medium, 2018, https://medium.com/dealspotr/influencer-marketing-tips-millennials-trust-da946f0bce18. Accessed Sept 2018.

“Study Identifies Beauty Industry Disparities On Youtube |”. Pixability.Com, 2018, https://www.pixability.com/recent-press-releases/study-beauty-industry-youtube-2014/. Accessed Sept 2018.

“The Latest Video Trends: Where Your Audience Is Watching”. Think With Google, 2018, https://www.thinkwithgoogle.com/consumer-insights/video-trends-where-audience-watching/. Accessed Sept 2018.

“Why Youtube Stars Are More Influential Than Traditional Celebrities”. Think With Google, 2018, https://www.thinkwithgoogle.com/consumer-insights/youtube-stars-influence/. Accessed Sept 2018.

“Youtube: Beauty Content Consumption 2017 | Statistic”. Statista, 2018, https://www.statista.com/statistics/294967/youtube-beauty-vlogger-content-consumption/. Accessed Sept 2018.

Dimmock, Caley. “Why Social Blade Isn’T Working And Why It Matters For Influencer Marketing”. Caley Dimmock, 2018, https://caleydimmock.com/why-social-blade-isnt-working-influencer-marketing/. Accessed Sept 2018.

Keller, Michael. “The Flourishing Business Of Fake Youtube Views”. Nytimes.Com, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/08/11/technology/youtube-fake-view-sellers.html. Accessed Sept 2018.

Lancaster, Brodie. “Glam Or Sham: How The Big Brands Cash In On Youtube’s Beauty Vloggers”. The Guardian, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2018/mar/08/glam-or-sham-are-youtubes-beauty-vloggers-selling-out. Accessed Sept 2018.