Verifying Facts in a Post-Truth World

In a digital world chock-full with misinformation, post-truth proclamations, and misleading headlines, it is harder than ever for one to fully trust the news. From that lens, it is safe to say that the spread of objective facts has hit a rough trough. That, though, has not curtailed fact-checking projects from springing up. Can the truth still set us free?

2016 Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year, via Mike Licht

“They are entitled to their own opinions, but they are not entitled to their own facts.”

That was Secretary of the Pilipino Presidential Communications Office Martin Andanar’s response to Human Rights Watch’s view of the country’s ruling regime as a “human rights calamity” per a recent BuzzFeed News article. Stern and with more than a hint of a factual divide, Andanar’s statement is par for the course in today’s political climate. Gone are the days of the carefully doctored executive press release response; today’s post-truth era of politics is instead characterized by unending debate over what constitutes facts (DeCesare 219).

Fading trust:

Among the numerous elements involved in this dangerous terrain of unpredictability is a now-common distrust of the news and how it circulates. Perhaps exasperating the problem is the fact, pun very much intended, that misinformation — or the “fake news” oxymoron that many are dangerously fond of characterizing it as being (Berger 7) — does not just affect politics; it also extends to entertainment, culture, and even medicine. Misinformation, simply put, is an inescapable part of our lives nowadays (Basu 225).

Media organizations of all sizes have themselves naturally embraced the transformation of the factual nexus and now continuously report on the war of attrition between the good news guys and the bad news guys. While such reporting is often times well intentioned, one could assuredly assume that it has only added to the uproar around the credibility debate. Indeed, while news organizations have consistently attempted to embrace their seemingly destined role as guardians of public interest, there is strong evidence pointing to their propensity for selling scandals and inciting outrage among audiences in a way that, it could be argued, has further served to decrease the industry’s overall legitimacy (Cerase and Santoro 335).

To their credit, though, many media organizations publically acknowledge their role in constructing our controversially controversial post-truth world. Even Facebook, arguably the company most associated with the misinformation phenomena, is now attempting to introduce new tools that allow audiences to report unsubstantiated facts on its platform.

While one could only hope for these efforts to prove successful, some public perception indicators predictably point out that the lack of trust that many have in news — particularly those being shared across social and interactive media, which if we’re being honest are a large majority of all current news (Prier 57) — might be rooted too deep (Roese 322).

A matter of fact:

To stem the tides of these waves of discontent, several initiatives are beginning to emerge in an effort to prove or disprove widely shared news pieces and in turn legitimize facts once again. Among the more notable examples of such initiatives was Mexico’s Verificado 2018.

As the country prepared to face its largest-ever local elections over the summer — with more than 10 thousand candidates running for office — a group of media organizations, including publishers from all over the world, banded together under the aim of limiting election-related misinformation. The goal was inherently journalistic: help the public identify truths and debunk everything else.

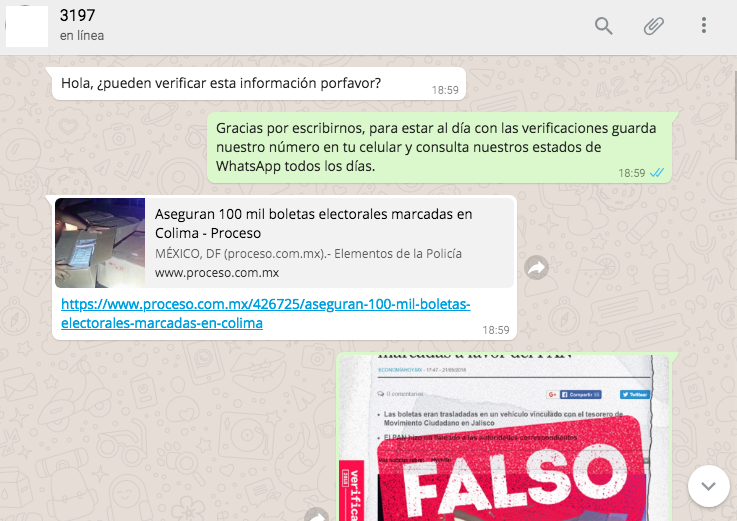

Verificado placed a great emphasis in these efforts on WhatsApp, the Facebook-owned encrypted-messaging app that is the most popular social interaction tool in Mexico. Understanding that WhatsApp is more personal than public social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook, Verificado set up a public verification line with especially trained full-time journalists where users could inquire about the factuality of news pieces in a private setting. The initiative’s fact checkers would then update Verificado’s WhatsApp page with around 10 different statuses per day to affirm or refute the authenticity of the most shared news pieces to aid the general public with their information consumption.

A screenshot of Verificado’s use on WhatsApp, via Nieman Lab

Verificado’s simple yet innovative fact checking contributed in helping the Mexican public make informed decisions in their choice of political representatives, with the initiative ultimately receiving the Online Journalism Award for Excellence in Collaboration and Partnerships, beating out joint efforts of publishers such as The Guardian and The New York Times along the way.

More importantly, perhaps, is the fact — no pun needed here — that through its success, Verificado now serves as an example to follow for fact-checking projects, particularly ones related to the tricky medium of instant messaging, across the world. In other words, the general spread of fact checking, influenced by Verificado and otherwise, has created an environment where other ambitious initiatives could exist and flourish.

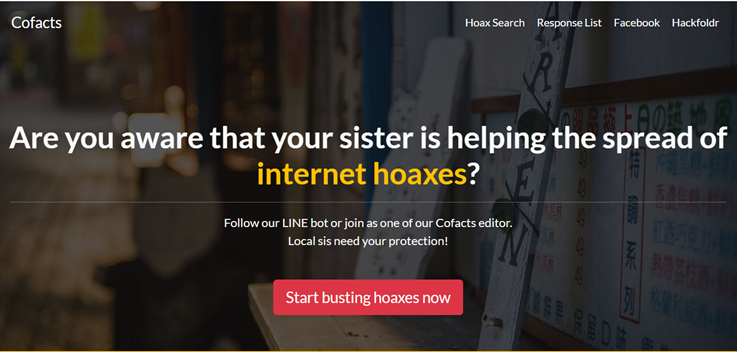

Take for instance the rapid rise of Cofacts, a Taiwan-based fact-checking enterprise focusing on another popular messaging app, Line. The initiative goes even one step further than Verificado in its integration of a uniquely designed chat bot to corroborate facts in a timely and efficient manner. The focus of Cofacts isn’t just politics; the initiative aims to serve as a quick go-to fact checker for a slew of messages of varied compositions across Taiwan. Adding an automated layer to proceedings has proven essential in such strive, with Cofacts’ chat bot answering over 35 thousand inquiries across the summer alone.

A screenshot from Cofacts’ website

Facing facts:

The noted successes outlined above of crowd-sourced and automated solutions could very well provide a solution to the uniquely digital misinformation endemic that has plagued the world recently. This isn’t to say that the problem is going away; it is not. Thanks to tools such as Verificado and Cofacts, however, separating fact from fiction is one click away, at least for those aware of the tools’ existence — and therein lies the bigger future challenge: informing the average citizen of the true magnitude of misinformation and the tools available to right the prevalent wrongs. Using accessible tools to make facts just as easy to reach as their fictitious counterparts is a vital step in this regard; us humans will have to do the rest.

Misinformation might indeed be a great divider, but the truth is still out there. In fact, it is still within reach.

Works Cited

Alba, Davey. “How Duterte Used Facebook To Fuel the Philippine Drug War.” BuzzFeed News, BuzzFeed News, 4 Sept. 2018, www.buzzfeednews.com/article/daveyalba/facebook-philippines-dutertes-drug-war?utm_source=Daily%2BLab%2Bemail%2Blist&utm_campaign=a3d047270c-dailylabemail3&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_d68264fd5e-a3d047270c-396212329.

Basu, Laura. “Curing Media Amnesia.” Media Amnesia: Rewriting the Economic Crisis, Pluto Press, London, 2018, pp. 210–239. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt21kk1x3.10.

Berger, Guy. “Foreword.” Journalism, Fake News and Disinformation, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, edited by Cherilyn Ireton and Julie Posetti, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France 2018, pp. 7–13, unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0026/002655/265552E.pdf.

Cerase, Andrea, and Claudia Santoro. “From Racial Hoaxes to Media Hypes: Fake News’ Real Consequences.” From Media Hype to Twitter Storm: News Explosions and Their Impact on Issues, Crises, and Public Opinion, edited by Peter Vasterman, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2018, pp. 333–354. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt21215m0.20.

DeCesare, Anthony. “Working Toward Transpositional Objectivity: The Promotion of Democratic Capability for an Age of Post-Truth Politics.” The Good Society, vol. 26, no. 2-3, 2018, pp. 218–233. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/goodsociety.26.2-3.0218.

Funke, Daniel. “CrowdTangle Now Lets Users Report Potentially False News.” Poynter, 11 Sept. 2018, www.poynter.org/news/crowdtangle-now-lets-users-report-potentially-false-news?utm_source=Daily%2BLab%2Bemail%2Blist&utm_campaign=81a11cac7e-dailylabemail3&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_d68264fd5e-81a11cac7e-396212329.

Gyenes, Nat, and An Xiao Mina. “How Misinfodemics Spread Disease.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 30 Aug. 2018, www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/08/how-misinfodemics-spread-disease/568921/?utm_source=Daily%2BLab%2Bemail%2Blist&utm_campaign=3a22062e29-dailylabemail3&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_d68264fd5e-3a22062e29-396212329.

Matsa, Katerina Eva, and Elisa Shearer. “News Use Across Social Media Platforms 2018 | Pew Research Center.” Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project, Pew Research Center, 10 Sept. 2018, www.journalism.org/2018/09/10/news-use-across-social-media-platforms-2018/?utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=newsletter_axiosmediatrends&stream=top.

Owen, Laura Hazard. “WhatsApp Is a Black Box for Fake News. Verificado 2018 Is Making Real Progress Fixing That.” Nieman Lab, 1 June 2018, www.niemanlab.org/2018/06/whatsapp-is-a-black-box-for-fake-news-verificado-2018-is-making-real-progress-fixing-that/.

Prier, Jarred. “Commanding the Trend: Social Media as Information Warfare.” Strategic Studies Quarterly, vol. 11, no. 4, 2017, pp. 50–85. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26271634.

Roese, Vivian. “You Won’t Believe How Co-Dependent They Are: Or: Media Hype and the Interaction of News Media, Social Media, and the User.” From Media Hype to Twitter Storm: News Explosions and Their Impact on Issues, Crises, and Public Opinion, edited by Peter Vasterman, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2018, pp. 313–332. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt21215m0.19.

Splice, Kirsten Han. “Taiwanese Cofacts Fact-Checks Information on LINE.” International Journalists’ Network, 29 Aug. 2018, ijnet.org/en/blog/taiwanese-cofacts-fact-checks-information-line?utm_source=This%2Bweek%2Bin%2BIJNet%2B-%2BEnglish&utm_campaign=ef32418650-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2018_08_31_06_42&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_d71e0ded42-ef32418650-15353041.

Terceros, Belén Arce. “Ahead of Mexico’s Largest Election, Verificado 2018 Sets an Example for Collaborative Journalism.” International Journalists’ Network, 29 June 2018, ijnet.org/en/blog/ahead-mexico%E2%80%99s-largest-election-verificado-2018-sets-example-collaborative-journalism.