Swipe you left out of my life!

How the features of tinder encourage both connectedness and social indifference

As the world is becoming more digitally connected and people are becoming more reliant on the Internet and digital technologies for various aspects of their lives, it comes to no surprise that people have shifted their romantic search from offline to online as well (Deuze 1).While dating websites have been around for various years, previously targeting a rather more senior cliente, dating apps, such as Tinder, have changed the online dating spectrum for younger generations.

Alaina Wibberly

The dating app Tinder offers users a large pool of possible romantic partners, and with this emergence of location-based real-time dating apps, a new way of interaction between individuals has been introduced (Gatter, Hodkinson 2: Ranzini, Lunz 81). Since its launch, the app has been part of various academic debates, as of how it has changed the dating culture and has contributed to the normalization of the so-called “hook-up culture” (Sevi, Tuğçe and Eskenazi 1). In the most basic sense, the app Tinder emphasizes on human connectedness and provides the possibility of swiping your way into a new potential date, thus stimulating users to connect to new partners (Van Dijck 12). While one the one hand the “swipe feature” has the purpose of encouraging users to connect to different partners and match, on the other it is believed that apps like these leave users more indifferent (Black: Robinson 24) .Though the act of swiping left and/or right is intensively superficial, it is most importantly the epitome of indifference and disposability. What one can observe then is the experience of real life through the interfaces’ logic, the screenlogic away from the screen.

This research will look into the into the construction of the interface of Tinder and analyze how it produces on the one hand the need for social connectedness, while on the other it leaves users emotionally indifferent. This will be done through the lens of the concepts connectedness and indifference. Additionally, because it is believed that smartphones have become an extension of people’s hands, the interrelationship between smartphones and humans will be explored as well, as this might also contribute to the effects Tinder has on its users and their connections/ relationships with other users (Lin 643: Leader). Thus, this analysis should shed light into understanding the detrimental effects of dating apps, such as Tinder, which are supposed to be built to facilitate dating but in the end are believed to leave a rather alienated social and emotional surrounding for its users.

Method

The aim of this research was to demonstrate how the interface and its features encourage both online social connectedness, as well as emotional isolation and indifference. Furthermore, the relationship between human ( hands) and technologies ( such as the touchscreen) was examined. This was done through a qualitative mixed methods approach, combining a thorough literature review, qualitative interviews as well as an interface analysis of Tinder´s basic features. This means that all possible features of the free Tinder version, as well as the layout of the app and its functionalities were analyzed, which will be one through a thorough interface analysis. The structure of the interface analysis will mainly focus on the contextualization of the concepts of connectedness, affordances and social indifference (or social isolation).

Literature review

As introduced above, Tinder has made an revolutionary mark in the growing trend of online dating apps and was set up to allow users to like (swipe right) or dislike (swipe left) other individuals with the swipe feature and interact with these potential matches. This smartphone application allows people to form relationships and bonds with other people with whom they have had no previous social ties (Hobbs, Owen and Gerber 272). The most known feature of Tinder is the so-called “swipe feature”, which has changed the online dating game completely. The fact that the choice of possible matches is reduced to a yes/no binary, simplified the process of “connecting” to various other users and gives the individual the perception of not having to make such an effort in order to be/ or get “matched” (Orosz, To’th-Kiraly, Böthe and Melher 518). Various studies have shown that this “swipe feature” is leaving users in a state of indifference, as the increase of virtual connections make real human relationships unstable and not as meaningful, as users enjoy a huge pole of possibilities (possible matches) and can exit any conversation with the swipe of a finger (Robinson 24). This results in a “binge – consuming” culture, in which people not only have a compulsion towards goods, but also in relation to other people’s (Passini 369). We are witnessing a rampant individualization due to technical change, as individuals are primarily seeking out romantic and/or sexual fulfillment via dating websites and applications (Robinson 25). The use of Tinder can to a certain extent be seen as a metaphor of “shopping” through potential partners, in which users have become products of consumption and the application itself the shopping catalogue. In this sense, Tinder increases personal individualization and consumerist values, while also influencing the dating world and dynamics of social relationships in the age of digitalization (Robinson 26).

Tinder also manages to gamify the search for potential partners using location, images and messages (as well as other features), which are supposedly making online dating easier and more fun than real life face-to-face meetings (LeFebvre 1220). Designed to ‘take the stress out of dating’, Tinder´s interface is built like a card game, seducing most prominently individuals between the age range of 18 to 29, which are also known as emerging adults, who are experiencing a period of romantic and sexual exploration (David et Cambre 1)

Interface analysis

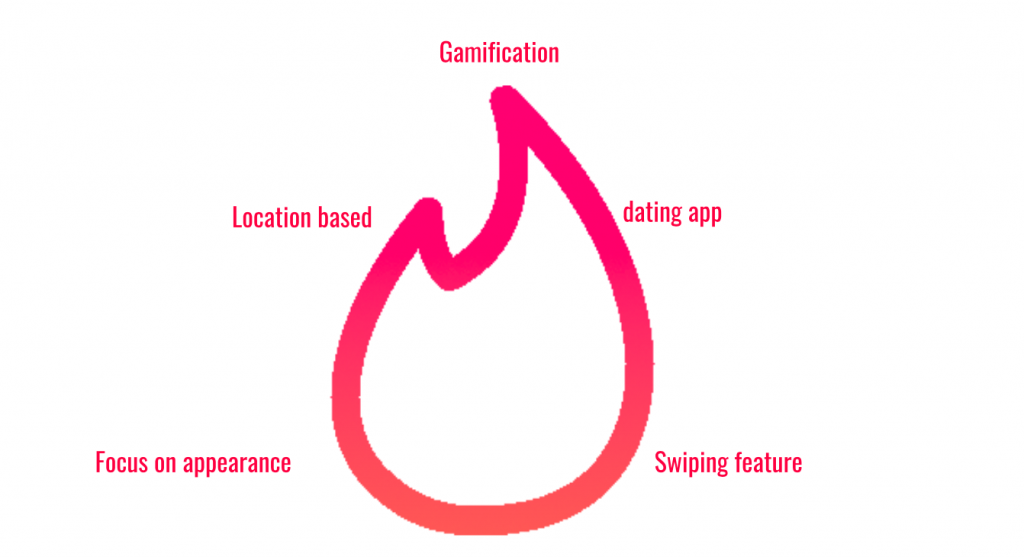

The first thing users see while downloading the app, is the app´s logo of the flame, which can signify various meanings. The most common associated meaning of the symbol of the flame relates to „heat“, „passion“ and „love“ (Blumberg 256). Additionally, the flame indicates that once their users have found a match, sparks will fly, hince the flame of passion (David and Cambre, 1). These are all rather positive significations of the logo, which are helpful in understanding the logic and affordances behind Tinder and the feeling of connectedness it can/ is supposed to evoke. As already explained, people make use of this app primarily to find a romantic or sexual partner, thus the prominent appearance of the flame on the app affords these positive thoughts of possibly getting connected with other users. On the other hand, the flame (fire), is also associated with fast destruction, especially destroying and leaving things in the past. The element of fire spreads very easy and fast and is always a evident threat for destroying houses, nature, people and non-living objects, and in this sense, fire demolishing things, places or people and leave them to the past. Contextualizing this to Tinder and the connections made through it, one can interpret the threat of fast destruction in relation to the fast pace “connections“ are capable of being destroyed and „burnt“ of the past (Blumberg 256). It is to remember that such symbolic interpretation might not be visible for the mere user to see, and might not have been created with such intent, but by looking into the business concepts of Tinder, such interpretation seems more than applicable.

Companies, like Tinder attract users with the social aspect of their product. Since people need these social experiences to satisfy the fundamental psychological need for belonging, Tinder allures a wide spectrum of users with the intent of social connectedness (Wolf, Kopf and Albinsson 15). This urge of social belonging is also reflected on their slogan” Match.Chat.Date”, which emphasizes (human) connectedness (Van Dijck 12). On the other hand, Tinder is known to rely mostly on short-lived connections, and not on deep and meaningful ones (Sevi, Tuğçe and Eskenazi 1). This is not only reflected on the abovementioned symbol of the flame, but also in their features.

The main purpose of the app is to connect with people, which is possible by swiping right and thus enabling the chatting function. This so-called “swiping” suggests not only connectedness but also indifference. One reason why this feature relates to indifference is the fact that many aspects of our daily experiences have transformed in the digital age and while the “swiping” encourages users to connect, is also allows as a mere function to keep people´s hand busy. Through the emergence of the touchscreen on smartphones, Ipads and other electronic devices, people have increased their usage of these devices for the sole purpose of keeping their hands busy (Leader: Lin 643). Adding to this, the minimal effort of “swiping” on the touchscreen strengthens the sensation of shopping through a bulk of potential partners, as an idea already introduced previously in this blog (David and Cambre 2). And while although matches are supposed to connect users, there is no limit into how many matches one can get per day. This can evoke the feeling of indifference and deprives their users to invest time and attention in each other. This phenomena is also known as a “binge – consuming” culture, where people also have a compulsion towards in relation to other people’s (Passini 369). Because the main characteristics of this concept are excessive, impulsiveness, and uncontrolled consumption of an object in a short period of time. On Tinder, the swiping feature makes the experience very limited, which can result in an excessive sensibility for boredom and the search for ever-new sensations ( Passini 374)

Another feature, which emphasizes the idea of social connectedness, are the daily suggestions given by Tinder. Through the use of algorithms, Tinder suggests daily six personalized profiles, which the user can immediately “super like”. This way, the user gets a more tailored option of possible partners, which is supposed to ease the search for the perfect match. When users super-like other users, an immediate notification pops up on the other users phone, which can evoke certain feeling of security and altered self-esteem. Normally, when users swipe right, the other user will not know if someone liked him/her, except if he/she swipes that user right as well. This personalized match suggestions increase the chance of a possible match, which corresponds to their vision of connectedness. But while these suggestions are supposed to give the user more personalized options for potential partners, it also furthers the feeling of indifference, as users are exposed to such a vast pole of options, thus not feeling the need to invest time not effort into one specific person.

The above mentioned features of TInder attract users to get connected and is a technological respond to overcoming the need of belonging and human connection. However, these features are also a form of gamification, which makes the search for potential partners using location, images and messages makes online dating easier and more fun than real life face-to-face meetings , which can result in acting indifference and shallow towards another (LeFebvre 1220). Because users might treat the app with ease as a normal “game” and because the affirmation of being needed and desired now also can be given online.

Interviews

To get more personalized information of how the app and the way it is built makes users feel in regards to connectedness and indifference, qualitative interviews were conducted. Overall, 15 interviews were administered, of which 8 were male and 7 female. All participants were straight and between the age of 20 and 28. The questions asked referred to the reasons of why they make use of the app and their personal relationship towards it.

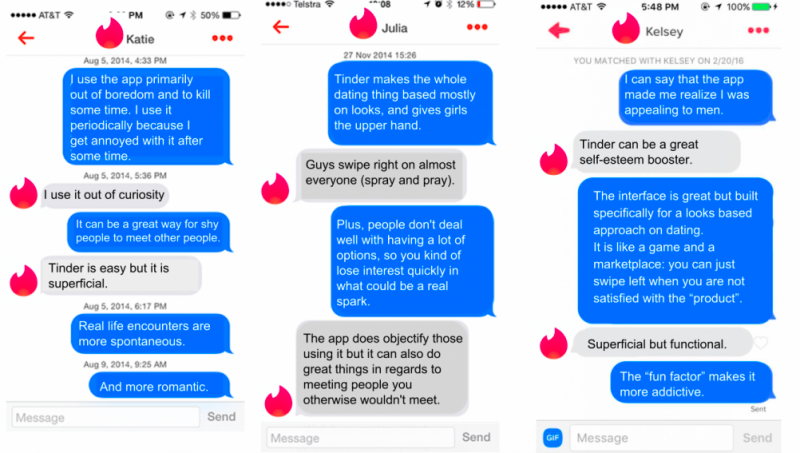

First, questions about the app itself were posed and overall, similar answers were obtained. Participants mentioned the superficiality of the app and explained how the interface encouraged them to focus more on physical appearances rather than anything else. All the respondents said that the design of the app was fun, which made it addictive for them. Half of them saw the app as game-like and the other half affirmed the theory that it can be seen as a “human” marketplace, giving dating a consumerist aspect. The subsequent questions related to the relationship the users had with the app itself, why they use it and how they use it. Many interviews said they used the app when bored, as a way to kill time, to keep their hands busy. This once again affirms previous mentioned theories, such as the one from Leader, who was researched how technology is changing the way people use their hands. According to him, individuals in the digital era feel the need to keep their hands busy, and smartphones present a perfect tool for such “occupation”, especially the swipe, scroll and click (Leader, 2016). Taking Leader´s theory and contextualizing it to Tinder, one can compare the use of the app to the action such as of knitting, which is also an activity that keeps you and your hands busy.

Extract of conducted interviews in reconstructed conversations

All users started using the app because they were curious what the fuss was about and what it had to offer. Two thirds of the interviewees ended up actually making real connections through the app, meeting friends and partners this way. A couple of the male participants noted the abundance of options available on the app, which is according to them one of the reasons why users lose interest so quickly; there is an insufficient effort made by users to maintain and sustain (possible) relationships with other users. In this context, other participants added that because of this vast amount of possibilities, users have become more demanding and tend to disregard others with more ease. When asked about the difference between meeting someone on Tinder and in real life, half of the girls said they preferred real life encounters, as they see it as more authentic. From the interviews, the idea can be derived that through the spontaneity of meeting people in real life, connections and relationships are qualitatively more valuable, and not as quantitative and physically superficial as the ones made on Tinder.

The next question aimed at finding out how users feel when they use the app. All females agreed that getting more and more matches helped to boost their self-esteem. Most male participants agreed that it is easier for females to get matches compared to them, and that they felt less comfortable with the objectification. This is an interesting finding, as it has an historical social debate that females are the ones offended by the sexualized objectification. Interestingly, one female participant said that she felt guilty while chatting to various matches at the same time. She did not feel true to herself when she was using the app, talking to several people simultaneously and therefore not being faithful to one person seemed disruptive to her.

Conclusion

According to the interviews and the interface analysis, the conclusion can be derived that there is an emotional indifference happening through Tinder. The app, or the marketplace as several interviewees defined it, gave the participants the impression that the superficial encounters they have on the platform are simply for fun and therefore they will not invest in the relationship as much as they would have in a real life setting. The interviewees care less for their tinder encounters and understand them as part of a game, Tinder game. Some might be uncomfortable with this idea, but whether they like it or not they still end up behaving without care and indifferently on the app. Indifference is part of the rules of the tinder game and is directly implied through the interface and its features.

Due to time constraint, certain topics were left out for discussion. Further research could implement a possible explanation for the change of gender perception through the use of Tinder, such as that female respondents felt more empowered than the male ones, as well as analyze the success ratio of online vs. offline meet-ups through the use of the app.

References

Andersen, Christian Ulrik, and Soren Bro Pold. Interface Criticism: Aesthetics Beyond the Buttons. Aarhus University Press, 2011.

Black, Marie. “Tinder Just Added a Big New Feature for Gold Members.” Tech Advisor, 28 June 2018, <www.techadvisor.co.uk/feature/software/tinder-3515013/.>

Blumberg, Neil H. “Arson update: A review of the literature on firesetting.” Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online 9.4 (1981): 255-265.

Bucher, Taina, and Anne Helmond. “The Affordances of Social Media Platforms.” The SAGE Handbook of Social Media, SAGE Publications Ltd, 2018, pp. 233–53, doi:10.4135/9781473984066.n14.

David, Gaby, and Carolina Cambre. “Screened Intimacies: Tinder and the Swipe Logic.” Social Media + Society, vol. 2, no. 2, 2016, p. 205630511664197, doi:10.1177/2056305116641976.

Davis, Jenny L., and James B. Chouinard. “Theorizing Affordances: From Request to Refuse.” Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, vol. 36, no. 4, 2016, pp. 241–48, doi:10.1177/0270467617714944.

Deuze, Mark. “Mobiliteit En Leven in Media.” (2010): 1-15.

Gatter, Karoline, and Kathleen Hodkinson. “On the Differences between Tinder versus Online Dating Agencies: Questioning a Myth. An Exploratory Study.” Cogent Psychology, edited by Monika Kolle, vol. 3, no. 1, Apr. 2016, doi:10.1080/23311908.2016.1162414.

Hamilton-Parker, Craig. The hidden meaning of dreams. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc., 1999.

Hobbs, Mitchell, et al. “Liquid Love? Dating Apps, Sex, Relationships and the Digital Transformation of Intimacy.” Journal of Sociology, vol. 53, no. 2, June 2017, pp. 271–84, doi:10.1177/1440783316662718.

“Indifference, n.1.” OED Online, Oxford University Press, http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/94446. Accessed 12 Oct. 2018.

Leader, Darian. “Darian Leader: How Technology Is Changing Our Hands.” The Guardian, 21 May 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/may/21/darian-leader-how-technology-changing-our-hands.

—. Hands: What We Do with Them – and Why. Penguin UK, 2016.

LeFebvre, Leah E. “Swiping Me off My Feet: Explicating Relationship Initiation on Tinder.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, vol. 35, no. 9, 2018, pp. 1205–29, doi:10.1177/0265407517706419.

Murphy, Michael. Swipe Left: A Theology of Tinder and Digital Dating. p. 4.

Lin, Yu-Cheng. “The relationship between touchscreen sizes of smartphones and hand dimensions.” International Conference on Universal Access in Human-Computer Interaction. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013.

Orosz, Gábor, et al. “Too Many Swipes for Today: The Development of the Problematic Tinder Use Scale (PTUS).” Journal of Behavioral Addictions, vol. 5, no. 3, 2016, pp. 518–23, doi:10.1556/2006.5.2016.016.

Passini, Stefano. “A binge-consuming culture: The effect of consumerism on social interactions in western societies.” Culture & Psychology 19.3 (2013): 369-390.

Ranzini, Giulia, and Christoph Lutz. “Love at First Swipe? Explaining Tinder Self-Presentation and Motives.” Mobile Media & Communication, vol. 5, no. 1, 2017, pp. 80–101, doi:10.1177/2050157916664559.

Robinson, Holly. Tinder: The Marketplace for Love. p. 5.

Sevi, Barış, Tuğçe Aral, and Terry Eskenazi. “Exploring the hook-up app: Low sexual disgust and high sociosexuality predict motivation to use Tinder for casual sex.” Personality and Individual Differences 133 (2018): 17-20.

Van Dijck, José. The Culture of Connectivity: A Critical History of Social Media. Oxford university press, 2013.

Wolf, Marco, Dennis Kopf, and Pia A. Albinsson. “Marketization, Nostalgia, and Social Connectedness: An Exploratory Study in Eastern Germany.” (2016).