Sherlock Holmes of the Data-Driven world: ‘Big Data Policing’

Image: fcw.com

image: dreamstime.com

The emergence and rise of ‘Data Policing’, all around the world, is noticeable. And it is not a traditional use of technology by police, For instance, surveillance cameras in some public places. Nowadays we are encountering a completely novel phenomenon. AI-driven policing together with the rise of Big Data investigation methods and algorithmic decision-making processes is giving a new meaning to the concept of law enforcement. The police work is not what it used to be.

Perhaps Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of the fictional character Sherlock Holmes, would be surprised that new policing technologies are much smarter, faster and reliable than his legendary detective. And this new detective does not smoke! Ture, Sherlock Holmes was not a police offers. But are surveillance cameras, face recognition systems, or AI-driven predicting technologies inherently for police work?

Brave New World

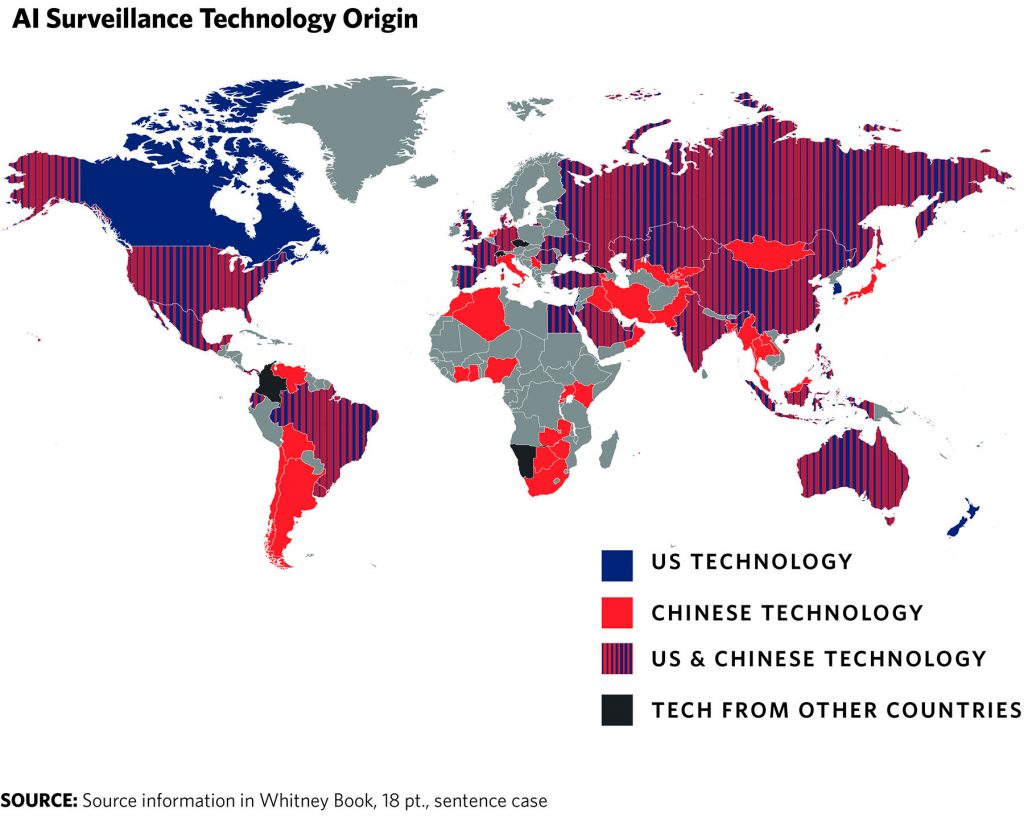

According to a report by International Peace, AI surveillance technologies “is spreading faster, to a wider range of countries, than experts have commonly understood” (Vaas). Not surprisingly, according to this report, liberal democracies are among the countries with the highest usage of AI-enhanced policing systems. But surprisingly Sherlock Holmes of our data-driven world is dependent on Chinese technologies. China is not only a giant user of these technologies but also a major supplier. In other words, western democracies are importing and using Chinese’ surveillance technologies massively in order to enhance their law enforcement organizations’ efficiency (Feldstein).

Steven Feldstein, the previously mentioned report’s author, and associate professor at Boise State University in an interview with AP expressed his concern about the consequences of these technologies: “I hope citizens will ask tougher questions about how this type of technology is used and what type of impacts it will have”. Feldstein, however, is not alone in expressing this concern. The academic journal, Surveillance and Society, devotes its latest issue (Vol 17/ No 3/4 / 2019) to the same concept: new models of policing. Different angles of this new endeavor by governments are being scrutinized by scholars in this issue of the journal: from consequences it might have for activists, the changing role of the riot police, blurring boundaries between citizens and law enforcement, to the possible human rights violations by the new methods of policing.

The legitimate use of technology to ensure public safety is probably a good reason to legitimize the usage of these technologies. However, our recent history is full of unlawful or harmful uses of technology. From Watergate to Cambridge Analytica scandal, there was always, in one way or another, a technology involved. Not to mention the leaked information about activities of intelligence Agencies by Wikileaks or by individuals such as Mark Snowden. Among many considerations that the concept of data policing bring on the table, it is probably one the most relevant issues to draw attention to the data ethics.

China is not only a giant user of these technologies but also a major supplier | Image: AP

Big Brother is Watching You

Image source: https://www.teepublic.com/tapestry/2960641-big-brother-is-watching-you

It has been discussed that since the concepts around data are usually considered merely mathematical phenomena, their potentially enormous consequences have been forgotten (Kitchin 22). However, being more aware of the subjective nature of these concepts could make it inexcusable to neglect ethical issues. Indeed, the urgency of considering ethical issues around data, made some scholars to urge their colleagues to begin thinking about these ethics and consider them in a far more serious way (Markham and Buchanan 202).

Dataveillance and the huge debate around it could only get enforced by the new policing technologies. Despite the enormous concerns about these issues, as Jagadish argues, “we are only beginning to scratch the surface today in our characterization of data privacy” (52). Van Dijck in response to uproars about data security and privacy, calls for a considerably serious digital literacy education (206) and boyd and Crawford consider it as a “key battleground” in the rapidly changing media environment (672). There are, arguably, far more considerations about these ethical issues. This wide range of concerns reminds us of the importance of thinking and talking about it.

More interestingly, Roderic Crooks in his

article Cat-and-Mouse Games: Dataveillance and Performativity in Urban

Schools, demonstrates how the novel digital technologies and data they

provide, could considerably alter the existing power relations: “omniscient surveillance

is a fiction: real surveillance regimes depend

on interpretation, even in highly automated systems. Digital data do not merely

represent some reality that is waiting to be categorized; instead, they

dynamically order and reorder the world” (Crooks 495).

He believes, not only in the case of data surveillance but also in other

subjects, we should not see digital data as a set of objective, “value-neutral

observations”, instead he suggests that these technologies should be

conceptualized as “the ability to produce statuses of norm and deviance” (484).

All in

all, there are more to think and much to say about the new AI-driven policing.

It can be concluded that we are suffering from a lack of humanities thinking

and researching, not only about this specific issue in particular, but about

various aspects of the data-obsessed world. It is to say that this case, among

the increasing concerns about the contemporary media environment and data

culture, illustrates the need for comprehensive data literacy. A strong social

study of technology and further humanistic analyses and knowledge could allow

us to comprehend how technology could or should shape social conditions. The rise

of data policing all around the world, once again, reminds us of the need to

carefully allocate much more thoughtful attention to the directions that the

technological developments are taking and about the consequences of these

developments

All in all, there are more to think and much to say about the new AI-driven policing. It can be concluded that we are suffering from a lack of humanities thinking and researching, not only about this specific issue in particular, but about various aspects of the data-obsessed world. It is to say that this case, among the increasing concerns about the contemporary media environment and data culture, illustrates the need for comprehensive data literacy. A strong social study of technology and further humanistic analyses and knowledge could allow us to comprehend how technology could or should shape social conditions. The rise of data policing all around the world, once again, reminds us of the need to carefully allocate much more thoughtful attention to the directions that the technological developments are taking and about the consequences of these developments.

Bibliography

- boyd, danah and Kate Crawford. “Critical Questions for Big Data: Provocations for a cultural, technological, and scholarly phenomenon.” Information, communication & society 15.5 (2012): 662-679.

- Crooks, Roderic. “Cat-and-Mouse Games:Dataveillance and Performativity in Urban Schools.” Surveillance and Society (2019): 484-498.

- Feldstein, Steven. Surveillance, The Global Expansion of AI. London: Carnegie International Peace, 2019.

- Ferguson, Andrew G. The rise of big data policing: Surveillance, race, and the future of law enforcement. New York: NYU Press, 2017.

Jagadish, H.V. “Big Data and Science: Myths and Reality.” Big Data Research 2.2 (2015): 49-52. - Kitchin, Rob. “Conceptualising Data.” Kitchin, Rob. The Data Revolution: Big Data, Open Data, Data Infrastructures & Their Consequences. London: SAGE, 2014. 1-26.

- Manning, Philip. “The Rise of Big Data Policing: Surveillance, Race, and the Future of Law Enforcement.” ontemporary Sociology 48.2 (2019): 170-171.

- Markham, Annette and Elizabeth Buchanan. “Research Ethics in Context: Decision-Making in Digital Research.” The datafied society: Studying culture through data. Ed. Mirko Tobias Schäfer and Karin van Es. Amsterdam: University Press, 2017. 201-210.

- O’brien, Matt. Researchers: AI surveillance is expanding worldwide. 17 09 2019. 20 09 2019. https://apnews.com/d1f77d3dd2684d7e8d7d47cbd192d8dd.

- Vaas, Lisa. Report: Use of AI surveillance is growing around the world. 20 09 2019. 2019 09 20. https://nakedsecurity.sophos.com/2019/09/20/report-use-of-ai-surveillance-is-growing-around-the-world/.

- van Dijck, José. “Datafication, dataism and dataveillance: Big Data between scientific paradigm and ideology.” Surveillance & Society 12.2 (2014): 197-208.