Deepfakes, Privacy Paradoxes and Black Boxes

“I do worry about my privacy,” Huang said. “Because no one cares about my data when I’m a nobody. But if people think they can make money from my information, it makes me worry about the security of my data.”

A user of ZAO, TechNode.

Introduction

ZAO is a deepfake app that was launched in China on the 30th of August 2019 and reached the top of the iOS store 48 hours later. The app generates a short video or GIF in which the user’s face is blended into the face of a celebrity such as Leonardo di Caprio or Marilyn Monroe. Wannabe movie stars have to upload one selfie (and their phone number) at least, but are encouraged to upload a series of selfies with different facial expressions (which would generate a more realistic deepfake). So far, it has only been possible to use ZAO if you have a Chinese phone number.

Unsurprisingly, a major privacy panic emerged only a few days after the app was launched. ZAO’s rating in the iOS store dropped to a 1,9/5 stars after more than 4000 negative reviews indicated worries about privacy and data collection. The popular multi-purpose Chinese platform WeChat has restricted access to ZAO “to maintain a safe online environment” (TechCrunch). Users of the ZAO have stated fear of their videos being misused to pay for goods not their own. Alipay (a popular mobile payment app) uses the Smile to Pay system which works by smiling at a camera at the cash register to pay. The privacy panic has prompted AliPay to come with a statement: “Rest assured that no matter how sophisticated the current facial swapping technology is, it cannot deceive our payment apps” (CNN).

The original user agreement gave ZAO full ownership and copyright to content uploaded or created on the platform, in addition to “free, irrevocable, perpetual, transferable and re-licensable rights” (TechCrunch). After the negative publicity ZAO changed its terms and conditions. This means that all content deleted by users will now be removed from ZAO’s databases and user’s content will only be used to improve the app. Having said that, when French security researcher Baptise Robert tested this, it proved that his video was still available online and not therefore not deleted from the database. His video can still be found online.

The Privacy Paradox

Privacy concerns around new technologies, such as ZAO, are not new at all. Citizens too showed great privacy concerns when Kodak invented the first portable camera in 1888. The Hawaiian Gazette published an article in 1890 that eerily echoes dystopian concerns heard today:

“Have you seen the Kodak fiend [devil]? Well, he has seen you. He caught your expression yesterday while you were in recently talking at the Post Office. He has taken you at a disadvantage and transfixed your uncouth position and passed it on to be laughed at by friend and foe alike. […] He is merciless and omnipresent.”

Castro & McQuinn, 2015, cited “Have you seen the Kodak fiend!” Hawaiian Gazette, December 6, 1890.

The particular privacy debate on ZAO has been pretty similar to the one on FaceApp this July. That discussion started out of a developer posting an alarming tweet that FaceApp would keep all your photos and upload them to their servers in Russia. This later turned out not to be true.

All this relates back to the academic concept of the privacy paradox. This is the idea that users of data-collecting services (such as ZAO) claim to be very concerned about their privacy but practically do very little to protect their personal data (Barth & de Jong 1039). When I used “ZAO app” as a search query on Google, most of the hits on the first page were articles by news or tech-websites that had the word privacy in the title, followed by a word indicating a negative (such as worry, concern, row, at risk). Google does not rank articles based on the ‘quality’ of content but on popularity, meaning that it can give us an idea of the public discourse around a topic (Rieder and Sire, 2013). Paradoxically today (September 18, 2019) ZAO is still ranked 3rd as the most popular free app in the iOS store in China (AppAnnie).

Most academic research on the privacy paradox has been done using social science methodologies such as surveys, risk-benefit calculations and social experiments (Kokolakis, 2011). The most popular theory stemming from this research is the privacy calculus theory: the idea that individuals perform rational calculus between their expected loss of privacy and the potential gain of the disclosure of their personal information (Kokolakis, 2011). I don’t think this theory suffices to explain the privacy paradox in our current media landscape. A media-studies based, critical view can help us to understand the privacy paradox better.

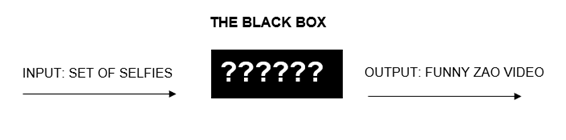

The Black Box

Another explanation for the privacy paradox can be provided working with the concept of the black box. (Disclaimer: this argument should not be seen as a pledge to go back to a media transmissions model.) A black box is “a device or system that, for convenience, is described solely in terms of it’s inputs and outputs. One need not understand anything about what goes on inside such black boxes.” (Winner, 1993). For the average media consumer (and even for media researchers) it can be very difficult to determine what precisely is happening inside the black box. Helen Nissenbaum (2011) also critiques the privacy calculus theory by pointing out the “ […] assumption that individuals can understand all facts relevant to true choice at the moment of pair-wise contraction between individuals and data gatherers.” (2011). Van Dijck and Poel (2013) see the idea of the black box as one of the core aspects of social media logic. They explain it as the “invisibility or naturalness of it’s [social media’s] mechanics: methods for [data] aggregation and personalization are often inaccessible to public or private scrutiny.”

Conclusion

ZAO is not the first media object where the privacy paradox comes into play and it will certainly not be the last. What would help is not to expect media consumer to open black boxes but let critical thinkers do this. Small efforts (like Bapiste Roberts test on ZAO) and big ones by platforms such as ProPublica and The Markup are good examples of this. Deepfake applications in all varieties (such as fake porn or fake speeches by public figures) are currently a hot topic. People should be made more aware of the workings and data-practices of the companies behind apps. Let’s try to prevent another privacy paradox: let’s try to prevent another mismatch between our intentions and our reality.

References

- Barth, Susanne and Menno de Jong. “The privacy paradox: investigating discrepancies between expressed privacy concerns and actual online behavior – A systematic literature review.” Telematics and Information, vol, 34, no. 7, 2017, pp. 1038-1058.

- Castro, Daniel and Alan McQuinn. The Privacy Panic Cycle: A Guide to Public Fears About New Technologies. Information Technology Innovation Foundation, 2015.

- Dijck, van José and Thomas Poell. “Understanding Social Media Logic.” Media and Communication, vol. 1, no. 1, 2013, pp. 2-14.

- Kokolakis, Spyros. “Privacy attitudes and privacy behaviour: A review of current research on the privacy paradox phenomenon.” Computers & Security, vol. 64, 2017, pp. 122-134.

- Nissenbaum, Helen. “A Contextual Approach to Privacy Online.” Daedalus, vol. 140, no. 4, 2011, pp. 32-48.

- Rieder, Bernhard and Guillaume Sire. “Conflicts of interest and incentives to bias: A microeconomic critique of Google’s tangled position on the Web.” New Media Society, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 195-211.

- Winner, Langdon. “Upon Opening the Black Box and Finding it Empty: Social Constructivism and the Philosophy of Technology.” Science, Technology and Human Values, vol. 18, no. 3, 1993, pp. 362-278.

Articles and Websites

- Carman, Ashley. “FaceApp is back and so are privacy concerns.” The Verge, 17 July 2019, https://www.theverge.com/2019/7/17/20697771/faceapp-privacy-concerns-iOS-android-old-age-filter-russia. Accessed 21 September 2019.

- Coleman, Alistair. “’Deepfake’ app causes fraud and privacy fears in China.” BBC, 4 September 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-49570418 . Accessed 18 September 2019.

- Dofmann, Zak. “Chinese Deepfake App ZAO Goes Viral, Privacy Of Millions ‘At Risk’.” Forbes, 2 September 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/zakdoffman/2019/09/02/chinese-best-ever-deepfake-app-zao-sparks-huge-faceapp-like-privacy-storm/#bd80feb84700. Accessed 21 September 2019.

- Fingas, Jon. “You can pay at a restaurant by smiling at a camera.” Engadget, 9 March 2017, https://www.engadget.com/2017/09/03/alipay-facial-recognition-payments. Accessed 21 September 2019.

- He, Laura, Jack Guy and Serenitie Wang. “New Chinese ‘deepfake’ face app backpedals after privacy backlash.” CNN Business, 3 September 2019, https://edition.cnn.com/2019/09/03/tech/zao-app-deepfake-scli-intl/index.html. Accessed 21 September 2019.

- Jiayi, Shi. “Ask China Anything: Would you use Zao to swap your face?” Technode, 10 September 2019, https://technode.com/2019/09/10/ask-china-anything-would-you-use-zao-to-swap-your-face/. Accessed 18 September 2019.

- Newby, Jake. “Viral Deepfake App ZAO Sparks Mass Downloads, Memes and Major Concerns.” RadiiChina, 1 September 2019, https://radiichina.com/china-deepfake-app-zao/. Accessed 18 September 2019.

- Paris, Britt and Joan Donovan. “Deepfakes and Cheap Fakes.” Data&Society, 18 September 2019, https://datasociety.net/output/deepfakes-and-cheap-fakes/. Accessed 21 September 2019.

- Schroepfer, Mike. “Creating a data set and a challenge for deepfakes.” Facebook Artificial Intelligence, 5 September 2019, https://ai.facebook.com/blog/deepfake-detection-challenge. Accessed 21 September 2019.

- Shu, Catherine. “WeChat restricts controversial video face-swapping app Zao, citing ‘security risks’.” Techcrunch, 3 September 2019, https://techcrunch.com/2019/09/02/wechat-restricts-controversial-video-face-swapping-app-zao-citing-security-risks. Accessed 19 September 2019.

- Quach, Katyanna. “Tempted to play with that Chinese Zao app for deep-fake frolics? Don’t bother if you want to keep your privacy.” The Register, 4 September 2019,

https://www.theregister.co.uk/2019/09/04/app_zao_deep_fake/. Accessed 21 September 2019.

- The Markup, https://themarkup.org/. Accessed 21 September 2019.

- ProPublica, https://www.propublica.org/. Accessed 21 September 2019.

- “Top Apps on iOS Store, China, Overall, Sep 18, 2019.” AppAnnie, https://www.appannie.com/en/apps/iOS/top/china/overall/iphone/. Accessed 18 September 2019.