“Swipe, swipe, vote“: Match your political opinion

You are sitting at home, watching Netflix, but you are still bored. How about a quick look at your smartphone? Before you know, you find yourself opening the online dating app Tinder, swiping left, right, left and checking out, which single is out there ready to mingle. But could you also imagine swiping for a match with a political party? The voting advice app VoteSwiper uses a similar feature like Tinder and puts political decision making into an entertainment context. “Going out and voting is as easy as dating online – but the “match” lasts at least one legislative period” (VoteSwiper), as the app states. Instead of finding your next date, VoteSwiper matches you with a political party based on your preferences.

Voting advice apps

There are various applications on the market, which help users in making a political choice. Voting advice apps share a common operating principle. By using a quiz, they line up the opinion of the user with the political position of various parties (Garzia, Marschall 377). Based on the individual’s choice between the presented positions, the app creates a rank-ordered list. It states, which party or candidate is the closest to the political preferences of the user (Alvarez et al. 229). Voting advice apps are a popular access to information. The goal of these apps is to encourage debate, enhance political education and increase voter turnout (Germann, Gemenis 150).

VoteSwiper

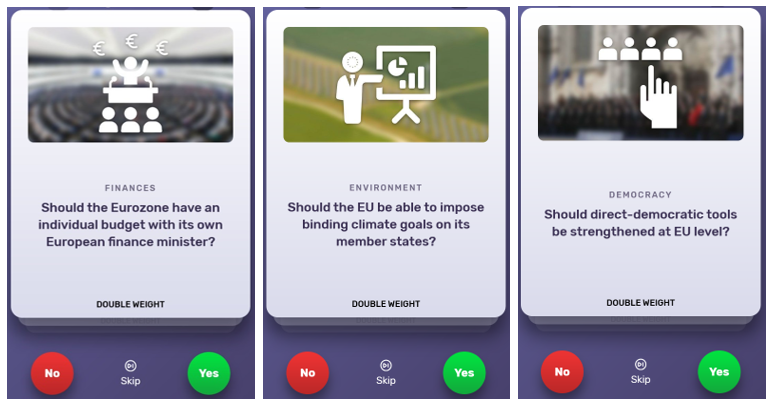

With each question VoteSwiper compares the user’s answer with the answers of several parties. If there is a match, VoteSwiper addresses one point to the matching party. If the user weights a question twice, the matching party gains two points. There is also the possibility to skip a question. In the evaluation at the end, the percentage designates how much the user matches the statements of the political parties. The team behind VoteSwiper consists of “journalists, political students, app developers, graphic artists, volunteers and video producers who worked together on the project in their spare time” (VoteSwiper). They develop the content in collaboration with independent partners, for instance universities. Currently the app is available for Germany, Austria, Sweden, France and Finland (VoteSwiper). The combination of VoteSwiper’s modern design, intuitive assessment and entertainment factor is supposed to motivate user for political engagement.

It’s a match – with your political opinion

Deciding whom to vote based on a match like on a dating app – that is the basic concept of VoteSwiper. The general features of voting advice apps are combined with the principle of the omnipresent dating app Tinder. Tinder matches singles based on their physical attraction to one another. It advertises with the slogan “Match. Chat. Date.” (Tinder). They welcome their users to the so-called “#swipelife” (Tinder). The slogan of VoteSwiper picks up the word “swipe” and includes it not only in its name, but also in its slogan: “Swipe, swipe, vote”. By adopting the language, which is typically known for Tinder, VoteSwiper presents itself as a voting advice app, which matches individuals with parties, representing the user’s political opinion. The general concept of VoteSwiper shows similarities to other voting advice apps. But due to the bridge the app itself builds to online dating, the process of developing a political opinion is put into an entertainment environment.

Political participation is an important pillar of a democratic society. As citizens we have the moral duty to vote with a sense of responsibility and to consider sufficient information in order to install a just government (Maskivker 36). Political resources, such as information and knowledge, are an important precondition for political participation. More information enables citizens to develop their own political opinion. Thus, they are more likely to vote. In this respect, the expanse of accessible information about political parties provided by VoteSwiper reduces the transactional costs of collecting relevant information. This increases the probability that the user will cast a ballot in the next election (Garzia, Marschall 8).

The idea behind VoteSwiper might mean well. But what does it say about our society, if voters need to be mobilized and interested in the political future of their country by a playful app, which relates itself to online dating? And what are the humanistic consequences of emphasizing entertainment instead of information? Although the bridge to online dating adds an element of entertainment to the process of gathering information, it can lead to a less meaningful life, which is “less consistent with the quirks of human condition” (Morozov 233). According to Neil Postman, “the intellectual powers of humans were developed by a medium that fostered abstract thought” (Postman 13). To what extend does VoteSwiper contribute to rational thought? By framing political perspectives in an online dating design, VoteSwiper shapes the information that people interact with. The app provides a basic insight on different political opinions. However, political knowledge is a complex phenomenon with multiple dimension consisting of diverse definitions as well as concepts (Schultze 48). Turning everything into entertainment, frames important topics as casualities. The speed and fluidity, with which the information through the mobile medium arrives, doesn’t encourage understanding or lasting recognition. The user absorbs facts for a split second and then swipes onward, without memorizing the content.

Conclusion

VoteSwiper is an entertaining way to get a first idea about the different political perspectives before an election. Nonetheless, it shouldn’t be the only source to gather information about a political party. Putting the information process into an online dating environment might get people interested but doesn’t foster rational thinking and therefore doesn’t produce fully involved voters.

References

Alvarez, R. Michael et al. “Party preferences in the digital age: The impact of voting advice applications.” Party Politics, vol. 20, no. 2, 2014, pp.227-236.

Garzia, Diego and Marschall, Stefan. “Research on Voting Advice Applications: State of the Art and Future Directions.” Policy & Internet, vol. 8, no. 4, 2016, pp. 376-390.

German, Micha and Gemenis, Kostas. “Getting Out the Vote With Voting Advice Applications.” Political Communication, vol. 36, no. 1, 2019.

Maskivker, Julia. “The duty to vote.” New York: Oxford University Press, 2019.

Morozov, Evgeny. “To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism.” New York: Public Affairs, 2013.

Postman, Neil. “The Humanism of Media Ecology.” Proceedings of the Media Ecology Association, vol. 1, 2000.

Schultze, Martin. “Effects of Voting Advice Applications (VAAs) on Political Knowledge About Party Positions.” Policy & Internet, vol. 6, no. 1, 2014, pp. 48-68.

Tinder www.tinder.com

VoteSwiper www.voteswiper.org/en