Unfolding Twitch Vernaculars through Emotes

Twitch is the largest and most popular video game live streaming platform, owning up to 72.2% of total hours watched compared to YouTube, Facebook Gaming, and Mixer (Perez). Not only is Twitch a gaming based streaming platform, but it also allows streamers to interact with their audience through categories such as In Real Life (IRL) and Just Chatting. Streamers can earn money through Twitch if they are a partner or affiliate through donations, subscriptions, advertisements, sponsorship, etc. Overtime, Twitch added more features to gain the properties of a social network allowing users to send direct messages, post status updates, like, share, and comment on the Twitch application (Stephenson, “Twitch: Everything You Need to Know”). Twitch affords a couple of unique features including the ability to develop third party integrations through the Twitch application program interface (API). One of those features are emotes, a way to interact with a live streamer through a meaningful image associated with a message or emotion. Emotes are shrunk down images with reference to vernacular jokes or memes that originated from Twitch or other platforms like 4chan and Reddit (Stephenson, “The 7 Most Popular Twitch Emotes of 2019”). Sometimes these emotes become so popular their usage starts to cross over to social media platforms such as Facebook or Twitter.

These third-party integrations enhance the world of Twitch emotes allowing streamers to add custom emotes to their channel. Some emotes are even more popular than Twitch’s own global emotes, since they are designed and ranked by the community. However, these custom emotes are only visible to users that install the specific web browser plugin that converts the trigger text such as “Pepega” and “AYAYA” into images. Hence, it is a form of a vernacular specific and unique to the Twitch chat community that an outsider may never understand.

Twitch’s Programmability

The concept of affordances in general describe “what material artifacts such as media technologies allow people to do.” (Bucher and Helmond 3). To discuss emotes through what Twitch affords: the platform enables the development and expansion of emotes by different parties through integrations. Twitch affords and encourages the integrations and widespread use of third party emotes through the programmability characteristics of its platform. As Bogost and Montfort argue that the essential characteristic of a platform is “programmability” (Plantin et al. 297), one of Twitch’s defining characteristics indeed becomes this programmability. The platform affordances make Twitch a platform that is uniquely customizable and programmable: “The service itself provides the streamers the technology and tools for streaming, and the streamers themselves often augment the stream with their choice of additional elements and tools.” (Sjöblom et al. 21). On the official website of Twitch, this is also promoted: “Twitch is a developer’s dreamland. Countless communities need custom tools built just for them. Come be their hero.” (Twitch, “About Twitch TV”).

The reasons why Twitch allows the programmability to an extent where streamers could have their own custom emotes could be discussed in terms of platform’s characteristics. Twitch emphasizes how the platform enables the creation of different communities, high levels of social interaction and engagement between the streamer and audience. It aims to extend the interactivity and connectivity between its audience and streamers through “different automated bots and tools in the streams, to further the appeal and communications practices of the streams” (Sjöblom et al. 20).

Twitch encourages users to contribute to the programmability and to interact through different emotes, leading to the creation of sub-communities where users and streamers can express themselves in different and creative ways through emotes, which could be called the vernaculars of Twitch.

Emotes as Vernaculars

Tuters and De Zeeuw conceptualize vernaculars as “group-based discourse, or sociolect, highly innovative novel forms of expression that are often intentionally obscure to those outside of the in-group” (5). Since BTTV and FFZ emotes are only visible to users with the extensions and seen by others as plain texts, their usage divides the viewers into outsiders and insiders, and therefore represents a vernacular activity performed by the extensions’ users.

However, not only that emotes are available to the ones with the related extension, every streamer may add their own emotes and there could be different vernaculars in each channel. The emotes viewers use are communicational actors that create a meaning between multiple parties: streamer, viewers and the platform. Features can be considered as communicational actors because they produce meanings and meaningfulness (Bucher and Helmond). Twitch’s broad community divides into individual channels with their own sub-communities sets of vernaculars. Twitch is also divided into multiple categories based on the game or activity the channel is currently streaming, which also ties into emotes specifically used for a genre of games.

On Twitch anyone could be both an insider and an outsider, because there are more than 27,000 streaming partners, 150,000 affiliates, and an average of 2.2 million daily streamers (Iqbal). Thus, anyone that frequently watches certain streamers may not understand the vernaculars tied to a different streamer, because there could be custom emotes specific to a channel. Streaming partners also have their own customizable emotes carrying unique meanings that do not require the installation of third-party plugins to display, but to trigger them the viewer needs to be subscribed to that specific channel. Twitch, BTTV, and FFZ encourages sub culture communities as it enables streamers to modify and control the use of emotes. Twitch’s platform and both plugins give streamers the freedom to ban and permit certain emotes to display within their chatroom, therefore limiting and controlling vernacular activity on the channel.

There are meanings and explanations associated with all cases of vernacular activity on the internet. Every emote available on Twitch has an origin and significance associated with its usage. One of the most mainstream global Twitch emote is “Kappa”, which is the picture of the former Twitch employee who implemented the chat client, Josh DeSeno (Alexander, “A Guide to Understanding Twitch Emotes”). To be considered part of the Twitch community it is required to know that “Kappa” signifies sarcasm. Another apparent example is “LUL”, which has multiple variations as a global Twitch, BTTV, and FFZ emote. It is based on a laughing image of Twitch streamer and Youtuber, TotalBiscuit (John Bain) who added the emote to Twitch, but was taken down due to legal issues with the photographer. Due to its popularity, Bain uploaded the image on BTTV and Twitch also brought it back as a global emote by applying a filter to avoid copyright issues. Unique to BTTV and FFZ, there are multiple emotes based on the infamous Pepe the Frog meme that originated from 4chan. Due to the interplay of ‘dynamism’ and ‘conservatism’ inherent to any memetic media (Phillips and Millner 42), there is an abundance of Pepe emotes that can be used to express different emotions, for example, “FeelsBadMan”, “FeelsGoodMan”, and “PepeHands” (express sadness).

An example of a custom emote that is vernacular to a sub community is “forsenE”, which belongs to one of Twitch’s most popular streamer, Forsen (Sebastian Fors) (Alexander, “How Twitch’s Most Popular Emote, ForsenE, Took Over”). The emote is a warped image of Forsen’s face recognized as one of the most used emotes of Twitch. The viewers from Forsen’s channel would spam this emote on other channels to troll streamers and assert dominance of Forsen’s community. Forsen’s community is unique as they tend to spread the trend of using new variations types of emotes all over Twitch and other platforms like Reddit and Twitter, which is the main reason why some emotes became so popular.

Through emotes, an outsider would get to know more about the overall fanbase and types viewers of a certain channel. Twitch emotes are a way of learning and understanding the behaviors of communities and sub communities that exist throughout the platform. Thus, understanding and keeping up with old, new, and emerging emote trends are an important part of understanding how the vernacular culture unfolds on Twitch.

Emotes Usage Insights

Identifying vernacular activity on Twitch can be a challenge due to the number of channels and total amount of emotes spammed on the platform. This leads us to the question of why certain emotes are an essential part of the Twitch community as a whole and how some emotes play an important role shaping sub community vernaculars among certain streamers and categories. Through the lens of meme affordances and the vernacular culture of the internet there are specific reasons why certain emotes are trending or unique to a channel in relation to the context of the stream.

To investigate how vernacular activity unfolds on Twitch through the usage of emotes we used the StreamElements Chat Stats Tracker to identify the top ten emotes from three categories (Top Global Twitch emotes, BTTV emotes, and FFZ emotes). StreamElements is one of Twitch’s major third-party developers that provides streamers with different types of software that aid them in enhancing viewer experience or offer insights about their audience. The Chat Stats Tracker tool, introduced by the company in 2016, tracks what emotes, hashtags and chatbot commands are used in chat rooms of connected channels in real time. It presents the top 100 emotes used globally and among specific channels dividing the emotes into three categories: Twitch, BTTV and FFZ. Therefore, the data collected with this tool can illuminate the tendencies in usage of first-party and third-party vernacular emotes in different channels’ communities.

To draw further analysis from the data we based it on the top five Twitch channels with the highest number of overall chat messages, as this number suggests a more active chat community. E-Sports, Special Events, and Non-English channels were excluded, because they would not be representative for the purpose of our project. Aiming to find streamers with distinct communities, we used the following channels in our analysis: Forsen, Xqcow, MoonMoon_OW, SodaPoppin and Loltyler1. The data were collected at 12:30 P.M. on 3 October 2019 and are shown in Tables 1-5.

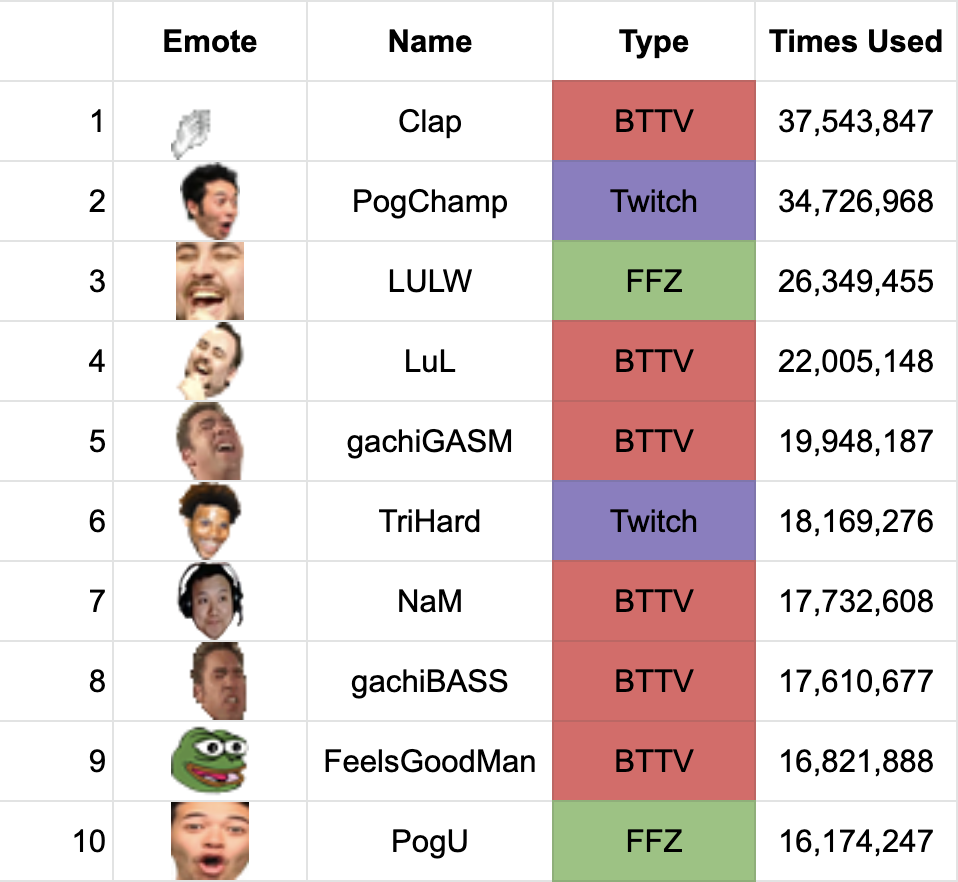

The initial observation that can be made from the data set is that a browser extension, either FFZ or BTTV, is a necessity for a person who wishes to join channels’ communities, as the combined usage of the third-party emotes either exceeds the usage of Twitch’s own in four out of five inspected channels. Loltyler1’s data does not follow the trend, as Twitch emotes take lead in the list of most used; however, the numbers of FFZ and BTTV emotes used suggest that they are still very popular in the streamer’s community. This observation becomes more prominent if we combine the uses of the emotes among all five channels to find the most used emotes. As Table 6 demonstrates, eight out of the top ten emotes belong to third-party extensions. This means that users without an extension become outsiders, as for them many chat messages partially lose their meaning or, at certain times, represent unintelligible combination of random words.

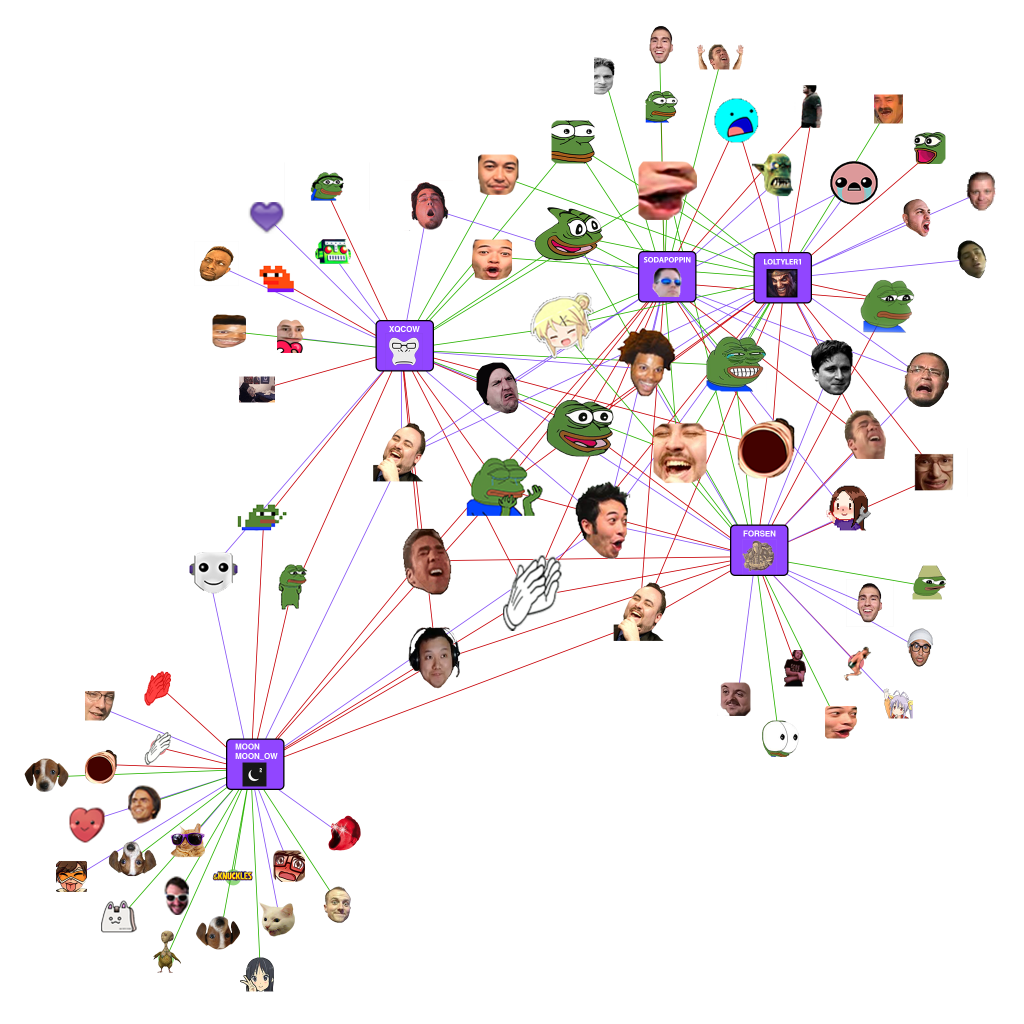

For a more in-depth exploration of the data set we exported it into Gephi visualization platform. Using emotes and channels as nodes, we connected every streamer with their most popular emotes with edges and ran the network through the ForceAtlas2 algorithm. We then adjusted the nodes sizes according to their Out-Degree ranking, making the emotes that are more prominent among the channels bigger. Lastly, we colored the edges according to the emotes’ source: purple for Twitch, red for BTTV and green for FFZ. The final result is shown in Figure 2.

This visualization highlights how Twitch’s programmability enables and shapes the vernacular activity that unfolds in the platform. Firstly, it enriches the common culture of emotes: despite the assumption that only Twitch’s Global emotes would be shared among different channels, many of the FFZ and BTTV emotes, which are afforded through the platform’s API, are widely used among the channels. For example, BTTV’s “Clap” emote is not only the most used one from the collected data, counting more than 37 million uses, it is also used in chats of all the inspected channels. Secondly, it lets the streamers build and reinforce their own sub-communities through the creation of their own vernacular emotes. All of the explored channels have some exclusive emotes, and they are not limited to Subscriber Emotes: these separated clusters also contain Twitch Global Emotes and third-party emotes enabled through the browser extensions. Thus, due to Twitch’s programmability, streamers’ subcommunities not only add their own vernacular emotes, but they also use inclusive publicly available emotes differently.

The graph also emphasizes the spread of Pepe the Frog vernacular across the channels. One of them, “PepeHands” representing a crying Pepe, is shared among all of the channels’ communities, but there are also other emotes with this character that can be found only in few channels. Some variations are even exclusive to a single channel, like “FeelsDankMan” and “MonkaOmega” that are only connected to Forsen’s channel in the graph. This spread is peculiar, as the character became associated with the alt-right during the US 2016 presidential election cycle and, judging by Twitch’s official emotes’ guidelines (Twitch, “Subscriber Emoticon Guide for Partners and Affiliates”), the usage of political symbols is prohibited on the platform. According to meme expert Don Caldwell, the spread of Pepe and the lack of the platform’s actions on it can be explained by the fact that this character was “completely divorced from politics” (Alexander, “A Guide to Understanding Twitch Emotes”) by Twitch users.

Perspectives of Future Research

This project aimed to demonstrate how vernacular activity unfolds on Twitch through the usage of emotes. We found that the platform’s affordances of programmability and modifiability enable and encourage vernacular activity in the form of emotes creation and circulation, whether it takes place inside the platform or in third-party extensions. While we found out that third-party emotes reinforce the exclusivity of certain vernaculars, as ‘outsiders’ without extensions see trigger texts instead of emotes, we also argued that being a part of a community does not only depend on having the related extension. By analyzing the data on emotes usage we were able to indicate how it affords the creation of channels’ sub-communities and their specific vernaculars. Through high-level of modification and control that Twitch affords its streamers to have on their own channels, every channel creates their own sub-community through a personalized usage of third-party emotes.

While our research project can be a good starting point to analyze emotes and sub-communities through vernacular activity on Twitch, it’s apparent that future research is important, especially on how emotes and vernacular activity on Twitch could be influenced politically. As Donald Trump launched his own channel on Twitch in October 2019 and started by streaming a rally in Minneapolis, Twitch became a platform that will be important to analyze in terms of politics (Kaser). However, with the start of Trump’s Twitch career, this might play out differently. Will Trump make use of emotes and create his own sub-communities by taking advantage of the programmability of the platform? How can emotes be used politically on Twitch? These are only some of the questions to raise for the near future. Although for now, emotes in Twitch affords a highly modifiable playground for anyone that wants to create their own sub-communities and vernacular activity.

Works Cited

Alexander, Julia. “A Guide to Understanding Twitch Emotes.” Polygon, 14 May 2018, https://www.polygon.com/2018/5/14/17335670/twitch-emotes-meaning-list-kappa-monkas-omegalul-pepe-trihard.

—. “How Twitch’s Most Popular Emote, ForsenE, Took Over.” Polygon, 29 Jan. 2018, https://www.polygon.com/2018/1/29/16938042/forsen-emote-twitch-ugandan-knuckles-meme.

Bucher, Taina, and Anne Helmond. “The Affordances of Social Media Platforms.” The SAGE Handbook of Social Media, SAGE Publications Ltd., 2017, pp. 1–42.

Iqbal, Mansoor. “Twitch Revenue and Usage Statistics (2019).” Business of Apps, 27 Feb. 2019, https://www.businessofapps.com/data/twitch-statistics/.

Kaser, Rachel. “Donald Trump Has a Twitch Channel and Now I’ve Seen Everything.” The Next Web, 11 Oct. 2019, https://thenextweb.com/media/2019/10/11/donald-trump-twitch-channel/.

Perez, Sarah. “Twitch Continues to Dominate Live Streaming with Its Second-Biggest Quarter to Date.” Tech Crunch, 12 July 2019, https://techcrunch.com/2019/07/12/twitch-continues-to-dominate-live-streaming-with-its-second-biggest-quarter-to-date/.

Phillips, Whitney, and Ryan M. Milner. The Ambivalent Internet: Mischief, Oddity, and Antagonism Online. Polity, 2017.

Plantin, Jean-Christophe, et al. “Infrastructure Studies Meet Platform Studies in the Age of Google and Facebook.” New Media & Society, vol. 20, no. 1, Jan. 2018, pp. 293–310. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1177/1461444816661553.

Sjöblom, Max, et al. “The Ingredients of Twitch Streaming: Affordances of Game Streams.” Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 92, Mar. 2019, pp. 20–28. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1016/j.chb.2018.10.012.

Stephenson, Brad. “The 7 Most Popular Twitch Emotes of 2019.” Lifewire, 21 Jan. 2019, https://www.lifewire.com/most-popular-twitch-emotes-4177985.

—. “Twitch: Everything You Need to Know.” Lifewire, 1 July 2019, https://www.lifewire.com/what-is-twitch-4143337.

Tuters, Marc, and Daniël de Zeeuw. The Internet Is Serious Business: On the Deep Vernacular Web Imaginary. 2019.

Twitch. “About Twitch TV.” About Twitch, 2019, https://www.twitch.tv/p/en/about/.

—. “Subscriber Emoticon Guide for Partners and Affiliates.” Twitch Help, 2019, https://help.twitch.tv/s/article/subscriber-emoticon-guide?language=en_US.