Shattering a totalitarian monopoly?

This blog post covers the struggle between Epic Games on one side and Apple and Google on the other. By suing Google and Apple over anti-competitive practices, Epic Games hopes to break the tight grip the platforms have on developers, creating open and equal access to everyone. Do we live in a world of totalitarian platforms, and will this be the start of a new era?

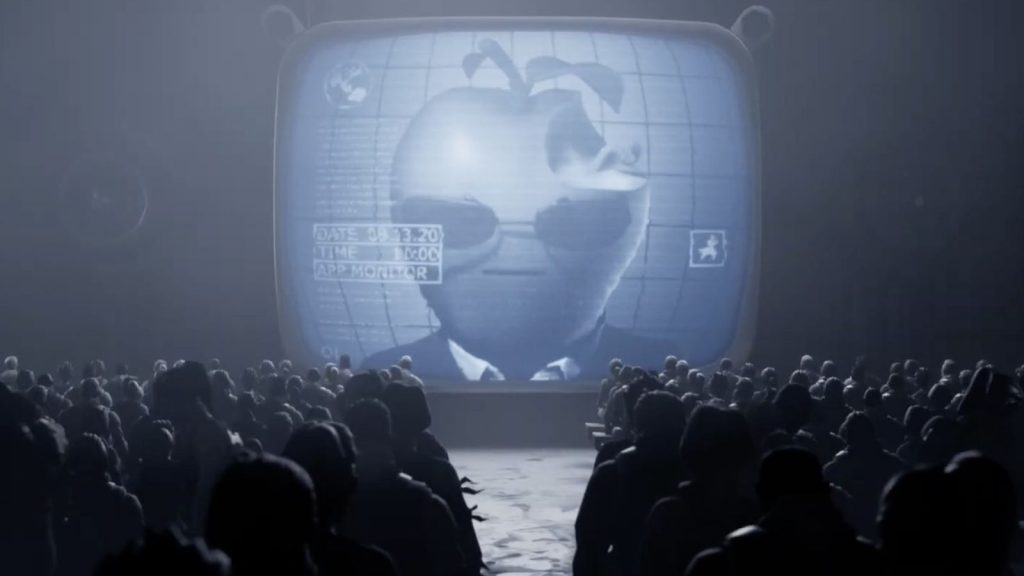

On August 13th, Epic Games launched a video titled Nineteen-Eighty-Fortnite, inspired by George Orwell’s dystopian novel (Fortnite, 2020). It was fueled by the removal of Fortnite from Apple and Google’s app stores after a dispute over the high sales commission (30%) on the platforms. As a legal response, Epic sued both Apple and Google over ‘anti-competitive practices (Carpenter, 2020).’

Fortnite’s Nineteen-Eighty-Fortnite commercial (Fortnite, 2020).

Epic’s CEO Tim Sweeney has positioned himself as the leader of a crusade against the totalitarian monopolies, particularly that of Apple. Does Tim Cook indeed lead an Orwellian dictatorship like Epic claims? What does the conflict between Epic Games and Apple say about platform gatekeeping in our time, and how it’s being challenged?

In our world of platforms

To make sense of Apple’s gatekeeping, it’s important to first look at the conception of power in the online environment; where is it drawn from? The control of Apple over its market is partially due to the mechanisms of platformization, defined by David Nieborg and Thomas Poell as ‘the extension of digital platforms into the web and app ecosystems (Nieborg and Poell 2019, 85).’

Platforms are multi-sided markets, negotiating both demand and supply. This nature of platforms leads to the accumulation of capital, increasingly concentrated in only a handful of platforms (Poell et al. 2019, 5). This platform capitalism is the economic governance of the internet. It doesn’t allow platforms a monopoly over the internet, but over the content uploaded on them and the users who consume it.

Aside from these macro-economics, Apple has much control over its own users when looking at the structure of an Apple device. For long, Apple’s design philosophy has been as simple and easy as possible, pure, and perfect (Isaacson 2011, 343-344). Although this allows for an easy, user-friendly, and safe interface, it is also very restrictive. There is only one way to get content to Apple users; via the established channel, the Appstore.

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/63823205/acastro_180604_1777_apple_wwdc_0002.0.jpg)

Apple’s devices are sealed off. There is a one-way entrance, and if you are banned, there is no way to reach the audience (Image: Castro, 2019).

Apple is, more so than Google, completely in control over what its subjects consume. Although Fortnite has been removed from both, Android players can still get around the ban by simply allowing non-Android apps. This circumventing doesn’t exist in iOS. The only options are either family-sharing or jailbreaking. Apple bans are much harder to circumvent, as people often lack the knowledge or skill to circumvent the demands of the Apple device to use the App Store (Davis and Chouinard 2016, 245-246).

It’s them – but also us?

The economic and material properties of our time are not single-handedly responsible for modern control and gatekeeping. Apple’s power over its users is enormous, but regular users are unlikely to encounter limits of what is acceptable (Gillespie 2018, 7). The normativity of the word ‘regular’ already betrays that power relations go beyond economics and design – it tells us what behavior is acceptable and possible. This aligns with Michel Foucault’s idea of the dispositif – Apple exercises power on its users through institutional, physical, regulatory, and administrative mechanisms.

Screenshot of the app allowing you to throw shoes at former

U.S. President George W. Bush, banned for ‘ridiculing public figures (Chen, 2009).’

From banning an app that lets you throw shoes at former U.S. president George W. Bush to banning Fortnite over contract violations, Apple users are jailed within the dictates of Apple, which causes questions about how far non-approved knowledge and what questioning of rules and guidelines are even possible. Gillespie states that this is inherent to any platform, however:

‘Platforms do, and must, moderate the content and activity of users, using some logistics of detection, review, and enforcement. […] Not only can platforms not survive without moderation, they are not platforms without it.’

(Gillespie 2018, 25)

Why do users use the authoritarian Apple? There is obviously no single answer to that question. Perceived prestige plays a role, but it’s far from the only one. The comfort of the Apple devices, in classical ‘bread and circus fashion,’ makes people less likely to resist Apple’s tyranny in its own device.

(Quote by the Roman poet Juvenal)

Moreover, users would more likely switch away from Apple if changing out of the ecosystem wasn’t such a hassle (Haselton, 2017). The notion of generative entrenchment also reinforces the power of a platform over audiences (Bratton 2015, 47). Investment in platforms makes them less likely to move to another one. And as audiences stay put behind a platform’s gates, companies can do little but play by their rules.

After Epic refused to play by Apple’s rules, the hashtag #FreeFortnite became trending on Twitter overnight, and Epic even launched a #FreeFortnite competition within the game. But what does this say about the way the authoritarian power of platforms is being challenged?

The #FreeFortnite cup (Epic Games, 2020).

Rallying to Epic’s banner?

If Epic breaks up Apple’s ‘unfair competitive advantage,’ will that lead to the open platforms and policy changes benefiting all developers? Because of the mechanisms behind the platform economy, it’s unlikely that there won’t be another platform that simply appropriates the void to create an open platform environment. This includes Epic Games itself. In an article by the Washington Post, a small developer remarked that Epic is also a closed garden, and that developers must similarly be approved by the game publisher (Park, 2020).

Moreover, we shouldn’t forget about brand loyalties and generative entrenchment. Even if Apple is forced to allow competition on Apple devices, it’s far from unthinkable that many people will stay with the App Store. It’s where people already are, and large amounts of apps are already present and can easily be downloaded.

If other platforms, such as Epic, are allowed to offer their services outside of the app store, it will be little more but a move on who is gatekeeping, rather than a move towards freedom. After all, Epic has shown similarly anti-competitive and exclusivist behavior on its own platform, like actively pursuing exclusivity deals (Gilbert, 2019).

Epic Games v Apple is at the very best a shift within gatekeeping. Although Apple has certain restrictions that other platforms do not have, such as complete control over a device, the environment from which the ‘monopolistic platforms’ grew still exists. The high sales commission that Epic tackles is the symptom, rather than the issue.

Superficially, this lawsuit can change the 30% sales commission paid, it could even nominally open up the App Store monopoly. But whether profound changes in the authoritarian power of platforms will change when one platform challenges another, seems far-fetched at best.

(Original Image)

References

Bratton, Benjamin H. 2015. The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Carpenter, Nicole. “Epic Games sues Apple, Google after Fortnite pulled from App Store.” Polygon, August 13, 2020. https://www.polygon.com/fortnite/2020/8/13/21367962/fortnite-epic-games-lawsuit-apple-ios-app-store.

Chen, Brian X. “Apple Says No to Throwing Shoes at Bush on iPhone.” Wired, May 2nd, 2009. https://www.wired.com/2009/02/apple-says-no-t/.

Davis, Jenny, and James B. Chouinard. 2016. “Theorizing Affordances: From Request to Refuse.” Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 36, no. 4: 241-248.

Epic Games, “Join the Battle and Play in the #FreeFortnite Cup on August 23.” Published August 20th, 2020. https://www.epicgames.com/fortnite/en-US/news/freefortnite-cup-on-august-23-2020.

Fortnite. “Nineteen Eighty-Fortnite-#FreeFortnite.” Published August 13, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=euiSHuaw6Q4.

Gilbert, Ben. “The Creator of ‘Fortnite’ is trying to shake up the PC gaming industry – here’s why a lot of fans are very upset over it.” Business Insider, April 9, 2019. https://www.businessinsider.nl/epic-games-store-situation-2019-4?international=true&r=US.

Gillespie, Tarleton. 2018. Custodians of the Internet: platforms, content moderation, and the hidden decisions that shape social media. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Haselton, Todd. “Here’s why people keep buying Apple products.” CNBC, May 1, 2017. https://www.cnbc.com/2017/05/01/why-people-keep-buying-apple-products.html.

Isaacson, Walter. 2011. Steve Jobs. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Nieborg, David, and Thomas Poell. 2019. “The Platformization of Making Media.” In Making Media: Production, Practices, and Professions, edited by Mark Deuze and Mirjam Prengers, 85-96. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Park, Gene. “Fortnite is trying to change public opinion about Apple. But small developers are lost in the debate.” The Washington Post, August 21, 2020. https://www.washingtonpost.com/video-games/2020/08/21/fortnite-is-trying-change-public-opinion-about-apple-small-developers-are-lost-debate/.

Poell, David, Thomas Nieborg and José van Dijk. 2019. “Platformisation.” Internet Policy Review 8, no. 4: 1-13.