The culture of speed

The “Accelerated Living conference” took place in Utrecht, last month, and it was part of the Impakt Festival 2009.

As the name may unveil, the conference theme was about the way we experience and how we approach time, speed and space from a number of perspectives given by the panel of speakers: John Tomlinson, Mike Crang, Carmen Leccardi, Steve Goodman, Stamatia Portanova, Dirk de Bruyn, Sybille Lammes, Charlie Gere, Jon Thomson and Alison Craighead.

What are the consequences of this accelaration for our senses and for our everyday life? What is the impact of technology on our experience of time, the blurring of boundaries between work and leisure time? What role played modernity and the rise of capitalism in this accelleration? These were just some of the questions that the speakers tried to answer during their presentations.

The presentation that was the most influential for me was the one by John Tomlinson who focused on two main topics:

- Modernity, supported by the idea of progress, in addition to the rise of capitalism made the issue of speed emerge as a cultural one;

- How immediacy and combination of capitalism, and the way communication technologies are becoming the digital mediator of everyday life, are changing the way we think, and how we experience work and leisure.

Tomlinson’s presentation theme was “the culture of speed – exploring the condition of immediacy”. Tomlinson followed a timeline of events to illustrate the evolution of speed in our society.

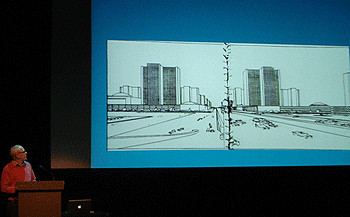

The type of speed first mentioned was the “mechanical speed”. Tomlinson started in 1909 with Filippo Marinetti’s Futurist manifesto that proclaimed a rupture with the past and the identification of man with the machine, velocity and the dynamism of the new century. Tomlinson then mentioned Le Corbusier’s idea of the new city, the city of to-morrow: “a city made for speed is made for success”. What Marinetti and Le Corbusier had in common, besides the period in which they lived, was the longing for a clear cut with the past.

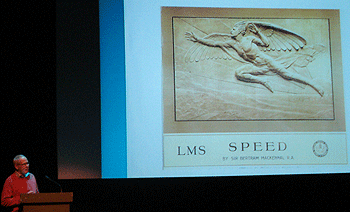

The LMS railway poster (with a photograph of a sculpted flying Icarus) shifted the presentation in another subtle direction: it opened the door to introduce a connection between work and speed.

The Icarus figure presented us with an idea of escape, liberation and heroism – the heroic power of speed – but also a sense of dignity of labor in controlling these powerful machines.

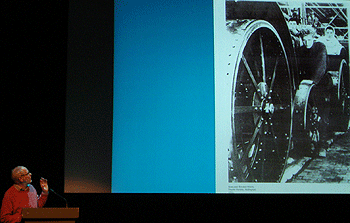

Taming the machinery that came along with the industrial revolution required hard work and was usually represented that way in imagery, as in the example presented of a photo taken in a factory in Stalingrad.

Tomlinson presented capitalism as an import source to understand speed.

The introduction of the concept of immediacy in which we live today was then introduced: immediacy in relation to time and in relation to space. By the increase of connections with other people and/or institutions we become increasingly present and available in our daily lives.

This immediacy promotes a new kind of intensity. An intensity that is promoted by the ease of use (the legerdemain) of the new media interfaces: web, mobile phones, etc.

In relation with this ease of use comes a sense of effortlessness in our work while using these interfaces. This can be contrasted with the hard work that had to be done in the Industrial age, when labor was dignified by effort.

This tendency to hide the complexity of such interfaces grouped with an immediate satisfaction of design is changing the consumer’s set of mind: things will come along; we don’t need to make a lot of effort.

With this argument Tomlinson offered the idea of blurring boundaries between what is work and leisure.

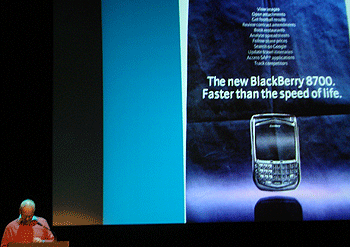

The image of a Blackberry advertisement demonstrated how new technology is being used as a way of keeping pace with the accelerated rhythm of life and how technology can be both the poison and the cure a way to extract more labor time than what was contracted.

When we book a flight online or shop something online aren’t we also performing delivery work, of course it is convenient to the consumer but isn’t there a shift from the producer’s tasks to the consumer. Do these practices seem like work or play?

According to Tomlinson, the challenge on responding to immediacy is to try to ensure that existential instances don’t collapse all together.

Tomlinson’s presentation was possibly the corollary of the first part of the semester topics; and is probably the reason why it was so appealing to me. It reminded me of:

– McLuhan’s arguments around that decisive moment in History, when Gutenberg’s invention and specially the movable type led to a myriad of irreversible social and technological effects;

– Vanevar Bush’s motivation behind the memex: hoping that more powerful tools would automate the routine aspects of information processing, leaving scientists and scholars with more time for creative thought;

– And finally Steven Shaviro’s text “Money for nothing” where Julian Dibbell’s concept of Ludo capitalism (the relationship between playing games, having fun and creating value in an economic sense) is mentioned when talking about second life and Ultima online.