Book review- Digital Folklore Reader

Reading Digital Folklore is like taking down that shoe-box of old photos from the top shelve and treating yourself to a night of reminiscing. You grimace at how goofy your hairdo looked 15 years ago and laugh at how you used to match pink leggings with animal print and secretly wish you would still lack the self consciousness that now keeps you from leaving the house looking like that.

Reading Digital Folklore is like taking down that shoe-box of old photos from the top shelve and treating yourself to a night of reminiscing. You grimace at how goofy your hairdo looked 15 years ago and laugh at how you used to match pink leggings with animal print and secretly wish you would still lack the self consciousness that now keeps you from leaving the house looking like that.

The Digital Folklore Reader is dedicated to “computer lovers, with love and respect” and it is an effort of the editors, Olia Lialina and Dragan Espenschied to fill the historical gap between Home Computer Culture and the emergence of The Cloud. It is a collection of essays and image artifacts that takes us back to a time when the Web was a vast playground for over-excited “naïve” users, otherwise referred to as “lusers”.

The book is divided into three parts. The first part, Observations- You can and must understand computer culture NOW, features essays written by the editors. Olia Lialina takes us back to the Vernacular Web, “the web of barbarians”, from the starry night backgrounds, the MIDI and GIF files that decorated every amateur webpage and were made available to all users through free collections of Web elements, to the chaotic underlying architecture of the Web, fed by the “many to many” linking principle. The essay also features a most interesting deconstruction of the URL structure and the tilde (~) symbol, which served as a reminder of the status of the user as a peripheral element. The final part of the essay is a eulogy to the “Mail Me” button that one would invariably find in amateur personal websites, which has now been replaced by the hits counter or the public comment sections on blogs. Lialina comes back to her essay in 2007 (2 years after the original piece), with A Vernacular Web 2. Here, she analyses the state of the user generated content in Web 2.0 and her conclusions are grim: the love-hate relationship that once governed the interaction between users and the Web is gone, as Web 2.0 “has turned into the most mass medium of them all.” (p. 59) There is a huge amount of user generated content online, but users are indifferent towards the Web, reduced to using standardized tools to express themselves creatively. The starry background that held promises of a future of unlimited possibilities has been replaced by glittery graphics that “decorate the Web today, routine and taken for granted.” (p. 67)

Dragan Espenschied also features three articles in this chapter of the book. His delightfully funny short piece on computer idioms is a critique of the metaphors used today to talk about computers, which he states are oblivious of the possibilities that they bring to our lives. Instead, he suggests taking a different approach to coming up with computer-related metaphors, from computers to real life- for example, when you want to suggest someone is stupid, you could call them “”bitmapped”, when you are faced with inner conflict, “it’s a Norton thing”. Espenschield also explains the technological and political aspects of creating browser-friendly fonts and uses the example of the famous Arial- Helvetica dispute to illustrate how cumbersome this process can become.

The second part of the book, Research, is a collection of interesting and relevant papers written by students from the Merz-Akademie. Helene Dams’ I think you got cats on your Internet takes a historical approach to the lolcat phenomenon in particular and the meme craze in general and manages to contextualize the emergence of “a gigantic, global insider joke.” Dennis Knopf’s essay Defriending the Web touches upon the economic interests that govern the online space and argues that we are permanently targeted by advertising or marketing research in all our online activity. Isabel Pettinato study about Viral Candy analyzes viral marketing, the stardom of viral video creators and the role of viewers in the popularization of these videos, while also taking a look at how marketing research makes use of the viewers’ feedback regarding viral content. Leo Merz traces the history of the Comic Sans MS font and brings to light the lively dispute that revolves around it in Comic Resistance, while creatively tying his subject to the use of vintage electronic music gear.

The third and final part of the book, Giving Back, is a collection of new media and design projects done by students at Merz Akademie, a tribute to users and their contribution to the Internet. The video below is just one of the projects featured in the book, The Real-Life Submit Button Model, by Johannes P. Osterhoff.

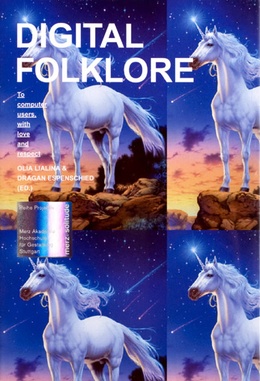

An important feature of the Digital Folklore reader is its carefully designed layout, the work of Manuel Buerger. The detachable cover is deeply rooted in the vernacular web. The outer side shows a repeated picture of a unicorn and a starry background, while the inner side is a collection of popular pixel icons, from geometrical forms, to pornographic images, political statements or popular characters. The cover that is revealed when removing this layer is refreshingly white, maybe symbolizing the content of digital culture before digital folklore. The pages of the book also hint at the first personal websites and give an amateurish impression, with text arranged into columns, colored pages, different fonts and many visual examples of the subject matter of the book. The playful design is extremely suitable for this equally playful book, which makes for a fun, interesting and refreshingly honest read.

Digital Folklore Reader

Editors: Olia Lialina & Dragan Espenschied

Designed by Manuel Buerger

288 pag + a cat poster

Published Nov. 2009 by merz & solitude