Twitter: immediacy and collective intelligence

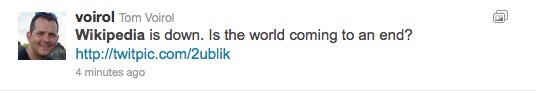

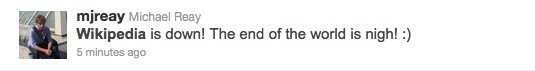

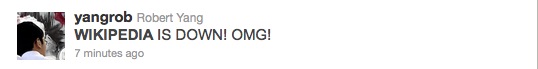

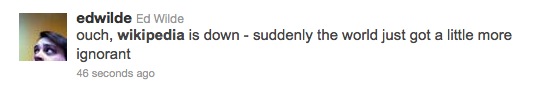

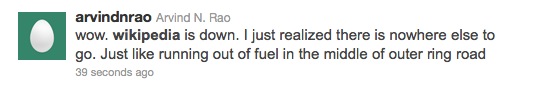

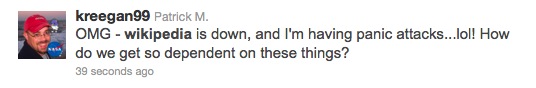

When working on a Wikipedia entry just last week, I was confronted once again with the helplessness one might experience when the computer does not work properly or when the internet connection is down. Upon typing in the Wikipedia URL, nothing happened. I found myself staring at the blank page before me. What is one to do? I refreshed the page, still nothing happened. Other web pages did open easily, so the internet connection was fine. There was not something wrong with my computer either, and I quickly concluded that there had to be something wrong with Wikipedia. But I wanted to know for sure, so I turned to arguably the most immediate and real time source of information that has “See what’s happening — right now” as its slogan. Twitter. See below some results for the query ‘wikipedia’ on sunday afternoon the 3rd of October.

Another example. Last friday, a part of The Hague city centre was inaccessible because the police had set up a perimeter and police cars were all over the place. Something had happened. But what? I was on the tram when I saw all this and I wanted to have my question answered. Luckily I carry a smartphone with me, so I had a quick look at the major news websites, but none reported on what just happened. Again, Twitter answered my question. Upon entering the general and vague police as a query, Twitter returned a satisfactory result. A local newsfeed reported in 140 characters that a shooting had just taken place and that police were investigating the scene right now. So, there you have it. Immediate and adequate answers.

What lies at the heart of the above accounts might be something greater than the limited functionality of Twitter itself. Twitter itself is simple. One creates an account and then can send a message comprised of a mere 140 characters to the rest of the world. It is that simple. One can easily tell by Twitter’s simple interface that Twitter itself is easy to use. But, as said, the above accounts implicate more than Twitter itself or alone does. What conclusions can we draw from the above experiences?

Back in 2000, Jay David Bolter wrote the article ‘Remediation and the desire for immediacy’. Although the article predates Twitter, what just happened in the above accounts can be neatly fit into an extension of Bolter’s ideas of remediation and immediacy. In his article, Bolter seeks to describe the ways in which new media increase immediacy, while at the same time make the medium itself more apparent. Thus, remediation consists of the incorporation of older media forms by newer ones and vice versa. Here and now is not the place and time to discuss the whole concept that is remediation. Let us instead highlight some key points of his article that are all the more applicable to Twitter.

“We are in an unusual position to appreciate remediation, because of the rapid development of new digital media and the nearly as rapid response by traditional media. Older electronic and print media are seeking to reaffirm their status within our culture, while digital media are challenging that status.” (p. 63-64)

If we tie Twitter, the traditional newspaper, and my personal experience all together, we may conclude that in the case of the shooting in particular, Twitter replaced the newspaper in that instance. I wanted to know what was going on right now and Twitter told me immediately. So, Twitter replaced the newspaper through its immediacy and its instant availability. However, the Twitter account that first reported on the shooting belonged to a local news station. Where Twitter may divert from older media, the older media had already acknowledged and appropriated Twitter’s possibilities.

In its own and unique way, if only for a moment, Twitter became a reliable news source. Also in the case of Wikipedia’s servers being down, Twitter, in a way, proved to be a source of news. I was frustrated that Wikipedia did not work. It turned out that Wikipedia was down for a mere ten minutes. But in that time Twitter was already full of messages about it.

So, Twitter is not only good for reading someone else’s thoughts or experiences of the day or providing news, but serves to be an expression of collective thought. The trending topics for instance express that. Henry Jenkins in “The cultural logic of media convergence” (2004): “The French cyberspace theorist Pierre Levy uses the term ‘collective intelligence’ to describe the large-scale information gathering and processing activities that have emerged in web communities.” (p. 35) We may view Twitter as a web community when considering Twitter’s trending topics and searching for ‘Wikipedia’ like I did. Large-scale information gathering and processing activities are both happening on Twitter, at least in the instances that I used Twitter for. Online tools like Twitter’s own search engine or Monitter can map the Twitter landscape to anyone’s liking.

In short, based on my two personal accounts, Twitter proves to be or do several things. Twitter can provide reliable news. It does not only do so at a random moment in time, but it is immediate as well. Searching for a topic on Twitter, or entering a query in Twitter’s own search engine, also expresses the idea of collective intelligence. Everyone knows (or experiences) something that all together forms a body of information that no single participant can contrive.

Bolter, Jay David. ‘Remediation and the desire for immediacy.’ Convergence, 6.62 (2000)

Jenkins, Henry. ‘The cultural logic of media convergence.’ International journal of cultural studies, 7.1 (2004)

Levy, Pierre. Collective intelligence. Cambridge: Perseus, 1997.