Why Led Zeppelin isn’t recommended for a Led Zeppelin cover band

The thesis, on which I recently graduated, has been my most thorough academic venture yet. This blog post offers a brief account of how my BA dissertation, titled “Off the record: Reconstructing the rationale behind Last.fm’s social music recommendation system,” came to be.

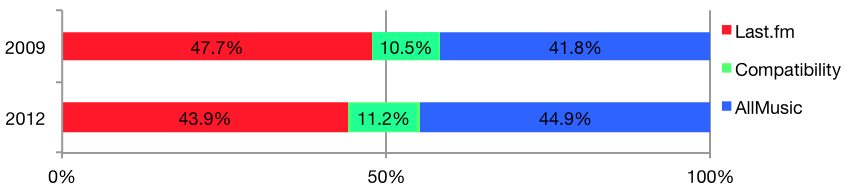

To a great extent, my bachelor thesis was prompted by a study on collaborative classification by Rose Marie Santini. Santini found that there exists a significant discrepancy between the editorial classification of music by experts and the collaborative classification of music by Last.fm users. This difference is expressed by the different recommendations both approaches to music classification produce for the same set of artists. Santini’s study suggests that the artists that are linked based on the social use of music, as on Last.fm, are profoundly different from the editorial selection of similar artists made by experts on AllMusic. On average, the weighted compatibility between these two recommendation systems was only 10.5 percent.

AM and FM – still on different bands?

My bachelor thesis partly represents a follow-up on Santini’s study. I was interested in finding if the gap between social and editorial classification had widened or narrowed. What I found instead was that the relation between two recommendation systems is remarkably stable. According to my own data survey, in which I used a comparative methodology known as domain analysis to examine the recommendations for the same set of artists, the weighted compatibility between the two recommendation systems still measures only 11.2 percent. This finding was salient because, on average, Last.fm and AllMusic grew by 48.1 percent in terms of unique recommendations. Furthermore, the listening data that drives Last.fm’s recommendations nearly doubled in the three-year intermediate period. In spite of all these changes, nothing had changed really.

Weighted distribution of music recommendations on Last.fm and AllMusic in March 2009 (822 recommendations) and March 2012 (1,197 recommendations) for the same set of artists (eleven in total).

Music and the wisdom of its crowd

The findings from the follow-up study led to what became the largest section of my thesis. In this section, I synthesize arguments from both supporters and critics of ‘Web 2.0’ and discuss the validity of these claims in relation to Last.fm. My thesis pleads in favour of Last.fm, an argument that I could substantiate with original findings from the follow-up study and the second section of my thesis, which examines the rationale behind Last.fm’s recommendations. Because Last.fm’s recommendations are based and what I’ve called ‘relative consensus’, the recommendation system is near impossible to corrupt without being dictated by populism – two of the main critiques against social forms of organization.

Last.fm’s recommendation system values relative recognition over absolute popularity. Amongst other things, this is expressed by the asymmetric similarity indications between artists, something I discovered by scrutinizing the underlying code. Janet Jackson, for example, ranks second on Madonna’s similar artists list, and is here considered to be ‘highly’ similar (valued ‘50.8’). Conversely, Madonna ranks no. 15 on Jackson’s list even though their similarity level is now marked as ‘super’ (valued ‘62.4’). While this seems counterintuitive at first – if two artists are considered similar, why isn’t their similarity level the same? – I demonstrated that this is actually very much alike to how similarity works in general. From a Janet Jackson listener’s point of view, Jackson and Madonna look much more alike than from the perspective of a Madonna listener, who has troubling seeing the same degree of similarity.

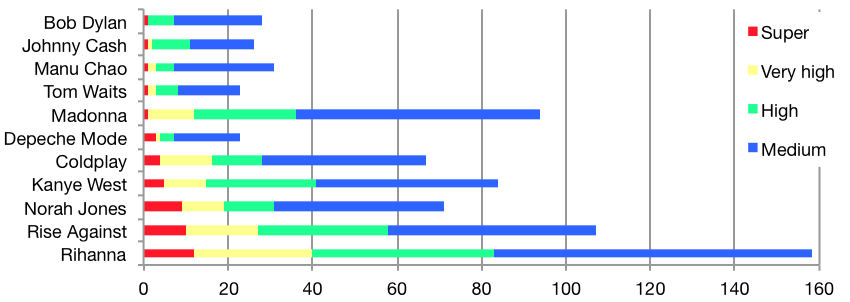

Seeing mutual listeners as an overlap between two artists can help to explain why a large overlap in listeners does not necessarily result in a high listing in the recommendations. The reason why Led Zeppelin isn’t listed amongst the 250 recommendations for a Led Zeppelin cover band is that the band is immensely more popular than ‘Letz Zep’ – roughly 1,300 times. The two thousand Letz Zep listeners on Last.fm may all listen to Led Zeppelin, but the other way around this is less than 0.08 percent. The gap is simply too big for any overlap to be significant. While this can be seen as a flaw, the same logic allows a lesser-known artist like Cher Lloyd (2.2 million scrobbles) to rank no. 4 on Rihanna’s recommendation list, topping established stars like Madonna, Christina Aguilera and Lady Gaga, who together account for over 300 million scrobbles. And again because Last.fm’s strive for consensus, some artists have more and ‘better’ recommendations than others, as the image below demonstrates.

Understanding how sites like Last.fm work is important, as recommendations systems have become “the dominant means on the Web by which information and knowledge are ordered” (Rogers 2009). By explaining the rationale behind Last.fm’s recommendations, my study made an effort to better understand how music recommendations work in general. This is important, because I believe that understanding how people socialize with music in real life is key to understanding why the critiques against social forms of organization do not apply to Last.fm. In fact, I argue that the social music recommendation system of Last.fm approximates how people interact with music in everyday life.