The Prosecution of Jokes on Social Media: Lets Ask the Audience.

19 year old Matthew Woods was recently sentenced to three months in jail for jokes he posted to Facebook.

For those unfamiliar with the case, details surrounding the crime are as follows. Matthew Woods — the 19 year old in question — had (according to the BBC) spent the evening of the 3rd of October drinking at his friend’s house before deciding to post a number of ‘abhorrent’ jokes on Facebook. The jokes were regarding the missing 5 year old April Jones, a case which has been receiving substantial media attention in the British press, and Madeleine McCann, a young girl who vanished from her family’s holiday home in Portugal in 2007. The press have been, somewhat sensibly, choosing not to publish the jokes made (exception is The Guardian, who decided to include reference to a number of the milder messages posted by Woods). However, for those wishing to gain further perspective on the level of obscenity involved, the alleged joke can be seen on this SlashDot forum.

Woods told the court he copied the joke from another website, believed to be Sickipedia.

A twist in Woods’ surprisingly quick charge, trial and sentence, comes in the form of the joke’s origins. It has been reported that Woods was not the original source for the material, but in fact found inspiration on Sickipedia, a site that dubs itself as ‘almost certainly the best online sick joke database in the world’. With that in mind, the courts involvement can be attributed to two things:

1. The nature of the forum – Sickipedia fits the bill of a public forum better than Matthew Woods’ Facebook wall (anyone can access Sickipedia if they so choose, where as it has been suggested that Matthew Woods’ privacy settings were not set to public). However, Sickipedia, even with its name alone, comes with some form of prior warning of the content within, whilst Facebook does not (although, in order to see Woods’ comments, it is likely that you would have to be his ‘friend’, which would indicate at least some degree of familiarity with his personal character). Therefore, the type of platform that the message was displayed on changes the audience viewing the material, which can account for:

2. The public response – According to Charlie Skelton, roughly 50 people turned up at his home threatening violence, with police arresting him at another address ‘for his own safety’. As Skelton goes on to highlight, the mob that turned up at his home was taken as a measurement for “public outrage”, indicating the gross offensiveness which constitutes the crime (also ignoring the fact that a mob response like this could technically fall under the Serious Crime Act 2007 of encouraging or assisting a crime).

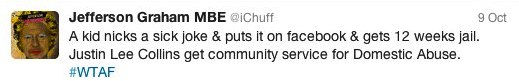

The importance of this case for freedom of speech online is obvious, and has joined a long line of recent cases being brought to court in the UK over the last year. In March, Liam Stacey was jailed for 56 days for posting racist abuse on Twitter surrounding the on-pitch collapse of English Premier League player, Fabrice Muamba. In July, an accountant had his conviction of sending ‘menacing’ tweets overturned. But perhaps most suprisingly, a day after Woods’ conviction, a man who posted an offensive message on Facebook stating “all soldiers should die and go to hell”, was sentenced to 240 hours of community service over a two year period. British courts now have such a mixed bag of case law precedent to choose from surrounding offensive messages, it is almost impossible to determine how your actions online will be punished, or whether you are even committing a crime.

Considering each of these cases revolve around communication that took place on social media platforms, it seemed fitting to take the pulse of the Twitter community regarding the ruling against Matthew Woods (which, unlike Facebook, has a general culture of making your tweets publicly accessible). Without such social media communities amplifying public awareness of tweets, comments and statuses, they would generally be lost in the ether of a previous posts. After all, a number, if not all of the 50 strong mob that turned up at Woods’ house threatening violence must have been Facebook users, and their (extremely questionable) behaviour can be considered the cause of the courts involvement. With this in mind, I gathered together all the tweets that I could find on the topic of the Matthew Woods case, which, at the time of research, totalled 1502.

- Personalised statements – any tweet which included a personalised message indicating the user’s stance on the ruling.

- Retweeted statements – any tweet which either retweeted another user’s stance, or retweeted a news article without any personalisation. The user is deemed as agreeing with the stance of the article where appropriate (for example, users sharing the article ‘Matthew Woods ‘joking’ about April Jones on Facebook is sick, not criminal’, by John Kampfner, were counted as ‘opposed to ruling’).

As mentioned above, they were then assigned a stance: opposing the ruling, supporting the ruling, neutral (which was generally made up of those that shared articles reporting the conviction without bias), and highlighting disparities. This final category was necessary to accommodate all users that were discussing the inconsistency of sentencing in a number of high profile court cases.

Quite predictably, the infographic demonstrates that at the time of research, the social media community on Twitter overwhelmingly disagree with the court’s ruling. The most popular opinion in the sample was that, whilst Twitter users condemned the joke as ‘sick’, this should not result in criminal punishment: