Digital Comics in the face of DRM

With the dominating presence of smartphone and tablet technologies within todays current market, it is clear to see why major comic book publishers have placed large amounts of focus and resources into the digital publishing frontier. Both interactive elements placed within digital comics themselves, and the eulogised benefit of being able to hold an innumerable number of texts, make the digitised archive format of comic book content a highly desired concept.

It is important to note that there are two forms of digital comics; the eComic, which is created using a computer and so carries its own digital format (allowing it be released through digital platforms), and then there are originally printed comics which have simply been scanned, re-coloured, and rereleased through digital means. Because of this, the comics expansion into digital publishing is extremely reflective of the move from printed to digital texts in their most standard form, and as such the benefits of the digital medium should be quite evident. There are apps available which act as ‘bookshelves’, essentially allowing the user to create their own collection, albeit in the digital realm. Furthermore, with hybrid forms of comics combining printed still image methods with elements of animation/cinematography, the medium of the printed comic is contending with a more engaging and stimulating model. However, whilst the potential of this digitisation of the comic book medium may seem relatively beneficial and innocuous, a number of issues have surfaced which have caused an extensive discussion, which involves itself with the rights of consumers and the concept of ownership.

There have been many concerns stated from the comic community regarding the readers rights to the product they are purchasing. As BoingBoing co-owner Cory Doctorow points out, the comic book industry has thrived around the borrowing, lending and reselling of comics (in their traditional printed formats). Furthermore, the comic book community is based upon the idea of readers hunting for used comics that they need to complete their collection, and the collecting of these ‘artefacts’ symbolises the nature of both comic book fan bases and comic book culture itself.

It is this aspect of comics that Doctorow believes is at stake, with the mainspring of this problem stemming not only from the digitisation of comics (as the gravity of this issue is diminished by the success of open access comic libraries), but more importantly the controversial presence of Digital Rights Management (or as non-officials are referring to it as; Digital ‘Restrictions’ Management – DRM). Because of these issues, one might wonder how comics are actually selling in their digitised, non-physical/collectable formats. However, as Galloway explains, the new spirit of capitalism is one in which creative expression is valued as labour, pure and simple (Galloway: 2007), suggesting that it is an intellectual labour which has become prioritised in todays information economy, allowing comics to become extremely successful within the online marketplace as a network.

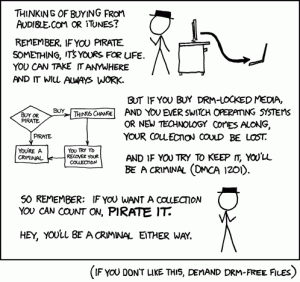

DRM, in its simplest terms, is the implementation of technologies that control what you as a consumer can do with the digital media content/devices that you own. Because of this, the outcry from comic communities is well justified, as the damages caused by DRM to consumers is devastating, as seen in the implementation of DRM in the video game industry! Sites which follow these codes of conduct can restrict the availability of content that consumers purchase, preventing them from being able to print, download, and essentially ‘own’ the product they have physically purchased.

An example of this can be seen in Marvel’s digital publishing front; Marvel Digital Comics Unlimited. Rather than ‘buying’ the comic, the reader is actually ‘buying access’ to it, and an extremely limited access at that, due to the online requirement and inability to download them to your personal computer. This can be compared to Zittrain’s stance on ‘tethered’ appliances such as smartphones and iPods, which require an ongoing communication between the consumer and the vender, effectively disrupting the consumers experience with the product they purchased (Zittrain: 2008).

Although the implementation of DRM is to prevent the reselling or redistributing of a companies intellectual property, the worth of the final product is severely reduced due to the lack of physical essence. This is especially problematic within the culture of comic books, as the ownership of a comic collection is something to be proud of, to look forward to contribute to, and most importantly, to share. In this sense, an issue regarding the politics of protocol arises, as the implementation of DRM by large companies is an example of control being placed upon the ownership of content as a restriction/limitation within their network (Galloway: 2006).

Whilst this problem has become a major concern of comic book culture, other projects, artists, and companies exist which respect the rights of the consumer and allow for the downloading of their digital products. Fortunately for readers of Marvel comics, the comics made digitally available are always physically printed, and it is still possible to control the product you purchase, and if you are too lazy to manage that then, as with all things there is always Piratebay.

References

Alexander R. Galloway, Geert Lovink & Eugene Thacker. ‘Dialogues Carried Out in Silence: An Email Exchange’, Grey Room (2007): 96-112.

Alexander Galloway, ‘Protocol versus Institutionalization’, in Wendy Hui Kyong Chun and Thomas Keenan (eds) New Media, Old Media: A History and Theory Reader, London: Routledge, 2006, pp. 187-198.

Zittrain, Jonathan. ‘Tethered Devices, Software as Service, and Perfect Enforcement’, in The Future of the Internet – And How to Stop It, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008, pp. 101-126