We Are Here: Locating micro-social dynamics of mediation

We Are Here (Dutch: Wij Zijn Hier) sums about 220 refugees that are actively searching for security and shelter in Amsterdam on a daily basis. In their very first blog post, they have stated their core objective:

We are here because our life is in danger. There are four reasons for this. War is the most important one … The second is political violence and oppression. Then there’s religious division. Finally there are in all our countries problems between tribes. All these causes are related, they’re mixed together. … So we are here because we face persecution and danger in our countries. We need to be in the Netherlands because this country is a free country where our lives are safe and we could build a future. (“New blog from Osdorp refugees!”, 12 Nov. 2012)

When requesting asylum, the City of Amsterdam had to reject their requests for shelter as they did not have any legal papers. As a result, these people have joined forces and created an organised collective (divided into five groups, represented by seven group leaders). They demonstrate on the streets, and use all means available to change their current situation. The group is maintained by the Migrant to Migrant (M2M) foundation, directed by Jo van der Spek, and is currently receiving help from many volunteers. They are here, in Amsterdam, and they want to communicate their specific problem to the public, so that we have to do something about it. It is in this situated context that we explored – through an ethnographic account – and reflected on their specific use of (new) media.

Fig. 1. One of the Dutch volunteers talking to a journalist while the refugees were moving from cultural centre OT301 (Overtoom 301, Amsterdam) to De Bron (Hugo de Vrieslaan 2, Amsterdam), a church in Watergraafsmeer where they coud spend the night of 1 Oct. 2013.

New media and visibility

Jo van der Spek as a journalist and activist deals with issues around migration like these, and notes that “the physical action in Amsterdam started one year ago. And, as soon as the action started [he], as a communicator, used the media to get power”. More specifically, they make use of new technologies like mobile phones and laptops to use Facebook (818 likes since 1 June 2012), Twitter (@wijzijnhierNL, 72 followers since 10 Sept. 2013), blogging (since 12 Nov. 2012), a mailing list (around 150 subscribers), and other media such as radio, television, interviews and presentations to inform the public about these tactical demonstrations in Amsterdam. Chekh El Mouthena, one of the refugees from Mauritania in charge of the demonstrations group, stressed the importance of these channels: “Out of direct action, out of media, out of Internet, we are nothing … spreading our message might bring us a solution”. This importance cannot be understated; “Through new media we are reporting the progress of our situation. This helps us to get more attention from the public. Repeated communication can make a change. If I’m still alive, I cannot keep silent”, explains Bayissa Kebede Ayana, refugee from Ethiopia, also involved in the mobilization of the collective. As long as they are able to keep their Facebook pages or Twitter streams updated, people will know the refugees are still alive and struggling, which makes it hard for the authorities to not do something about it. They are invisible by default, and visibility gives them power (that is, the social dynamics change). They not only have to make themselves visible, they need to maintain this visibility as well. That is, they need to keep posting and stay on top of the streams in an environment governed by algorithmic visibility (Bucher 2012) in order to remain ‘(a)live’.

Dynamics of reporting ‘(a)liveliness’

As mentioned above, We Are Here now deploys quite a range of new media devices. Facebook, which they regard as their main social media platform, now has around 800 likes (read followers), and this number keeps growing every day. Moreover, “there are quite a lot of reactions and likes on our Facebook”, says van der Spek. When asking around who was contributing which kinds of information and on which platforms, we found that specific members of the group had password access to the accounts and took responsibility for posting different kinds of information. However these dynamics of using Facebook are somewhat more complicated then this might suggest:

It is a community page, so everybody can post. Many of the refugees have their own Facebook page and they share and exchange content among each other. It’s messy, but it’s part of the culture of Facebook. We tried to make it more like a community thing, but it is not easy because people have no text writing experience, so most of them do pictures and music, not so much information and text, and what I do is mostly information, some pictures and audio as well. Audio on Mixcloud, and then link to it from Facebook and on the website. (Jo van der Spek, personal interview, 30 Sept. 2013)

This way, the different qualities that each of the refugees brings to the table contributes in a different way to the larger project. For instance, Osman recently gave a powerful speech, and van der Spek put the audio recording of it on Mixcloud. Similarly, some of the letters that Bayisa Kebede Ayana has written together with some of the volunteers have been published on the Wij Zijn Hier blog.

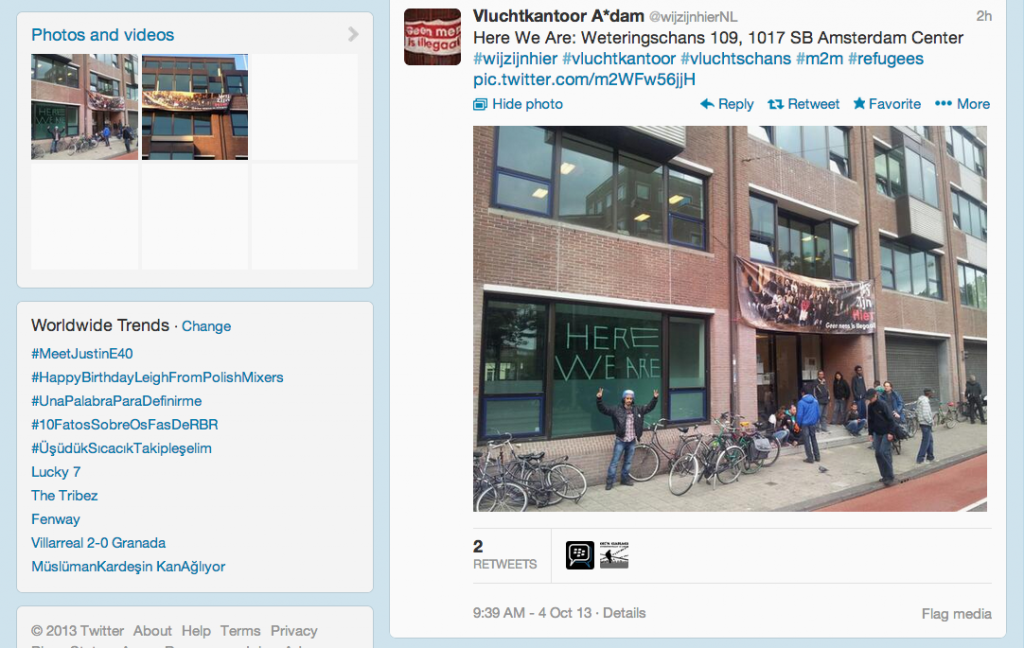

Fig. 2. “Wij Zijn Hier: Weteringschans 109, 1017 SB Amsterdam Center,” tweeted on Oct. 4, 9:39. (Screen Shot taken on 4 Oct. 2013, 21:22:06 of https://twitter.com/wijzijnhierNL/status/386168625620451328)

A paradox of mediation

This division of content production also has implications for the use of the different platforms. While Facebook and Twitter are mainly used for reporting on the liveliness of issues (e.g. what is happening; see Marres and Weltevrede 2013), the blog is used for providing “substance”, as van der Spek put it, which raises the question whether substance and liveliness are somehow opposing vectors. Here, we touch upon van der Spek’s understanding of media theory. Even though different media are utilised to distribute and amplify the visibility of the collective and the issues they are dealing with, the essence of the message lies here, here in Amsterdam. As he elaborates on his media theory, he explains:

Media is fundamentally a misunderstanding. Too many people take the media for the reality. The more media, the less communication. The more media you create, the less people understand each other. Understanding is trying to be together, looking each other in the eyes, doing things together. That’s what we are doing. That’s the fundament. The basic message is ‘we are here’. Just being together, without doing anything, is fundamentally a medium. And this attracts the media. Refugees are a medium in itself. (Jo van der Spek, personal interview, 30 Sept. 2013)

The media concept, then, is thus understood as a more general mediation of a set of conditions. As a result, their approach to using media is somewhat paradoxical in that it tries to amplify their message to a larger audience, but in doing so also does away with the need to be here in order to understand what is going on. The fundamental medium, as it is understood by van der Spek, seems to be obscured as a result of other layers of media on top of it, but at the same time it becomes visible through these layers of mediation.

When asking whether van der Spek considers himself an academic, he replied by explaining that he is ok with being an academic as long is that means being concerned with real people in real life. He develops his theory ‘on the ground’. This is very similar to the claim made by Leopoldina Fortunati (2009), that (sociological) theories are empowered by emotional accounts when analysis is integrated into them, these are what she calls “theories with heart” .This would lead to cross-fertilisation between empirical and theoretical accounts of research, and is especially important “in order to understand properly processes so complex as body-to-body and mediated communication” (14). It is no coincidence that the group names itself We Are Here, and not We Are Anywhere (nor They Are Here, for that matter). Situated context is of crucial importance here to understand the complex micro-social dynamics between media technologies and their users. In the same vein, we now return to the notion of the tactical.

Fig. 3. White marching banner with the text “Wij blijven hier in Amsterdam” (trans. We will stay here in Amsterdam). Posted by Jo van der Spek on Facebook, 30 Sept, 2013, with the comment “We are marching again.” (Screen Shot taken on 4 Oct. 2013, 16:18:13 of https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=660125667344666)

Tactical media

Above, we briefly mentioned the tactical dimension of this collective already. Although we could say a lot about tactical media itself, it would be contradictory to give the various definitions that have been given to the term since it originated from the nineties (although some references are listed below). If we want to understand what tactical media means, we need to locate it ‘on the ground’, and as it is put into practice. For van der Spek, the essence of tactical media lies in the combined use of artist activism and media to stage interventions.

Yesterday [Monday 29 Sept. 2013], when we were leaving the flats, everybody was sitting and waiting for us to go. And then I had nothing to do so I started doing what I usually do: collecting all the papers, posters, and pamphlets… Taking them from the wall and collecting them for the archive. But I found a white sheet and I thought that if we were doing a march we could use a banner. So when I came out there was a volunteer with nothing to do and she asked me ‘what can I do’ and I said to her ‘you can make a banner’. So she started to make the banner with other people there. A spontaneous action. I didn’t suggest more than ‘We Are Here’, but adding ‘… in Amsterdam’. And that was the message of the day because the move that the mayor wanted to make is to get us out of Amsterdam. This is a tactical moment. And they were carrying the banner during the march, and it’s also on Facebook. (Jo van der Spek, personal interview, 30 Sept. 2013)

The point of this anecdote is to show that the collective does not stage tactical media itself per se, but rather that the tactical moment produces or attracts other media practices, and as such it is tactical. However, if we take van der Spek’s view of the refugees themselves as fundamentally a medium, and if the tactical moment consists of enacting a specific social relation between the refugees and other social entities, then staging a tactical moment may be viewed as tactical media as well.

Conclusion

The ‘anecdotal’ account (Cubitt 2013) we set out to explore prompted us to rethink the importance of a situated account of the use of media both as concept and as practice. By looking at the theory through the lens of empirical reality, we were able to re-imagine the concept of tactical media in a situated context. This helped us understand better the close loop between theory and reality, and how both can benefit from each other. As a way of concluding, we would like to stress the relevance of studying the particular in order to find points of friction with other, often larger, social, technical, or theoretical entities. We think there is much to be gained from these ‘grounded’ analyses of mediation.

External links and organisations

Migrant to Migrant (M2M). <http://m2m.streamtime.org/>.

M2M Mixcloud. <http://www.mixcloud.com/jovanderspek/>

Wij Zijn Hier. <http://wijzijnhier.org/>.

Facebook (WijZijnHier). <https://www.facebook.com/WijZijnHier>.

Twitter (@wijzijnhierNL). <https://twitter.com/wijzijnhierNL>.

Wij Zijn Hier mailing list. <http://listcultures.org/mailman/listinfo/wijzijnhier_listcultures.org>.

De Vluchtkerk. <http://www.devluchtkerk.nl/>.

OT301. <http://www.ot301.nl/>.

De Bron. <http://www.kerkdebron.org/>.

Tactical Media Files. <http://www.tacticalmediafiles.net/>

References and further reading

Bucher, Taina. “Want to Be on the Top? Algorithmic Power and the Threat of Invisibility on Facebook.” New Media & Society 14.7 (2012): 1164–1180. Print.

Critical Art Ensemble. Digital Resistance: Explorations in Tactical Media. New York: Autonomedia, 2001. Print.

Cubitt, Sean. “Anecdotal Evidence.” NECSUS European Journal of Media Studies 3 (2013): n. pag. Web. <http://www.necsus-ejms.org/anecdotal-evidence/>.

de Certeau, Michel. “Walking in the City.” The Practice of Everyday Life. Trans. Steven Rendall. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988. 91–110. Print.

Dieter, Michael J. “The Becoming Environmental of Power: Tactical Media After Control.” The Fibreculture Journal 18 (2011): 177–205. Print.

El Mouthena, Chekh. 30 Sept. 2013. Personal interview.

Fortunati, Leopoldina. “Theories Without Heart.” Cross-Modal Analysis of Speech, Gestures, Gaze and Facial Expressions. Ed. Anna Esposito & Robert Vich. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 2009. 5–17. Print.

Garcia, David, and Geert Lovink. “The ABC of Tactical Media.” (2013): 1–3. Print.

Garcia, David, Geert Lovink, and Andreas Broeckmann. “The GHI of Tactical Media.” Transmediale.01 Festival (2001): 1–7. Print.

Guillory, John. “Genesis of the Media Concept.” Critical Inquiry 36.2 (2010): 321–362. Print.

Kebede Ayana, Bayissa. 30 Sept. 2013. Personal interview.

Kluitenberg, Eric. Legacies of Tactical Media. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2011. Print.

Lovink, Geert. “Tactical Media, the Second Decade.” Geert Lovink – Text Archives. 19 Oct. 2005. Web. 2 Oct. 2013. <http://geertlovink.org/texts/tactical-media-the-second-decade/>.

Marres, Noortje, and Esther Weltevrede. “Scraping the Social?.” Journal of Cultural Economy 6.3 (2013): 313–335. Print.

“New blog from Osdorp refugees!” Osdorp Refugees. 12 Nov. 2012. Web. 4 Oct. 2013. <http://kamposdorp.blogspot.nl/2012/11/new-blog.html>.

Omarou. 30 Sept. 2013. Personal interview.

Osman. “Last General Assembly in the Vluchtflat, Osman speaking.” Migrant to Migrant (M2M). Vluchtflat, Amsterdam, 30 Sept. 2013. <http://www.mixcloud.com/jovanderspek/last-general-assembly-in-the-vluchtflat-osman-speaking/>.

—. “Osman Speech We Are Here 1 Year.” Migrant to Migrant (M2M). World Garden of the Diacony, Amsterdam, Sept. 2013. <http://www.mixcloud.com/jovanderspek/osman-speech-we-are-here-1-year/>.

Phiffer, Dan. “Occupy.Here: a Tiny, Self-Contained Darknet.” Rhizome. 1 Oct. 2013. Web. 2 Oct. 2013. <http://rhizome.org/editorial/2013/oct/1/tiny-self-contained-darknet/>.

Raley, Rita. Tactical Media. Minneapolis/London: University of Minnesota Press, 2009. Print.

Richardson, Joanne. “The Language of Tactical Media.” subsol. 1 Aug. 2002. Web. 30 Sept. 2013. <http://subsol.c3.hu/subsol_2/contributors2/richardsontext2.html>.

van der Spek, Jo. 30 Sept. 2013. Personal interview.