The perfect bell pepper: from sheet film to Instagram

Some eleven or twelve years ago, I went to one of the many Turkish or Moroccan grocery stores in Amsterdam to buy a bell pepper. For the sixteenth time in a couple of weeks. I tried to find the cheapest store, not so much because I wanted to save money, but rather for aesthetical reasons: the bell peppers sold by regular supermarkets all have identical sizes and shapes. The cheaper ones have odd shapes, dents and bruises and were perfect for my purpose: shooting a portrait.

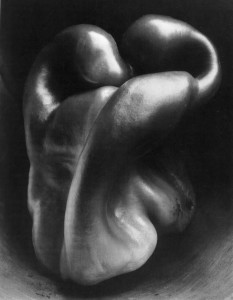

In my second year as a photo academy student, one of the most infamous assignments was to photograph a bell pepper to perfection. Not like the ones you see in supermarket brochures or newspaper ads, but like an attentive and even loving portrait, like Pepper No. 30, shot by American photographer Edward Weston.

Edward Weston’s Bell Pepper No. 30 (1930)

I spent countless hours in the photo studio, carefully moving the lights a few millimeters, adjusting reflection screens and flags and trying different shutter speeds and apertures, and then even more hours in a dark room developing the four by five inch black and white negatives, and printing them on expensive Baryta paper. Nevertheless, the first few attempts resulted in rapid and ruthless rejections by the teacher. And the rejections kept coming over the weeks that followed, until I could no longer look at a pepper, let alone spend hours with it in the studio.

This isn’t ancient history. This all took place in the twenty first century, after 9/11, after the introduction of the euro, and long after the web became mainstream media. Certainly, photo stores sold early digital photo cameras but serious photographers stubbornly stuck to shooting on film, using colour filters (actual pieces of glass, to be mounted on the camera’s lens) whenever special effects were required, and using very specific species of film to attain more (or less) vibrant or colourful results. Photography was a matter of skill, preparation and careful considerations. The ‘digital’ part usually meant shooting on film, scanning either negatives or prints, and then spending hours on early iMacs removing dust and scratches.

In the years that followed, all the lessons I had taken about dynamic ranges, film processing, enlarging negatives, mixing chemicals and manually retouching fine art prints became painfully obsolete. Most photo stores gradually started limiting their supply of film, chemicals and papers to one brand, sometimes because there wasn’t enough demand to justify a larger stock of the perishable chemicals, but also because brands stopped production and ceased to exist.

Fortunately, the demise of analog photography went hand in hand with a rapid improvement and availability of digital imaging technology. Soon, digital cameras were able to compete with analog SLR cameras and film on image quality, and as technological progress accelerated, digital cameras provided increasing light sensitivity, dynamic range, and sharpness. And – perhaps even more consequential – the camera’s powerful hardware and intelligent software made taking successful pictures easier and easier.

What literally tooks weeks to achieve twelve years ago – taking a more or less perfect picture of a pepper – can now be done in hours or less. Even if the original picture may not be perfect, the raw material’s flexibility is forgiving, and creating the perfect gradient from just off-white to just off-black in a bell pepper portrait is merely a matter of selecting an area on the computer screen, and applying a gradient adjustment layer in Photoshop, before wirelessly sending it to your softly humming photo printer.

In fact, I am tempted to try to recreate my final attempt at the perfect pepper (the one that was finally accepted by my teacher) using nothing but the camera on my iPhone and Instagram. As a Photo Academy graduate, having spent around € 20,000 on tuition fees, equipment and film, I should be feeling miserable about this apparent devaluation of the noble craft, but I’m not – if anything, I feel excited about where photography will be twelve years from now. I am more and more convinced it will be in our pockets, and it will be glorious.

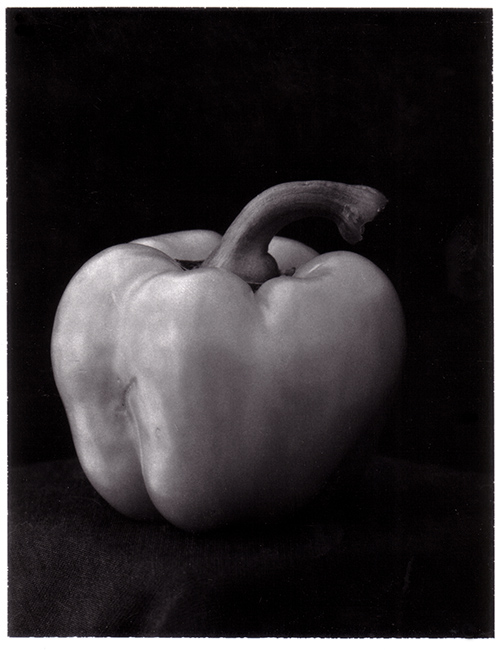

By the way, here’s my final attempt at the perfect pepper:

Pepper. Chemically shot, developed, printed and retouched (and then scanned) in 2002