Will SCiO be the Google of Physical Objects?

How many calories are in the cake you are eating? Does that medicine contain caffeine? Is your shirt really 100% cotton? SCiO, A small new sensor, molecularly scans objects and instantly displays their nutritional or chemical make-up on your smartphone. Will SCiO change they way we experience the physical world around us?

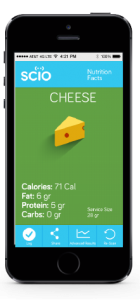

SCiO scans objects and instantly displays their make-up on your smartphone (Photo: Consumer Physics)

Smartphones and search engines have made information easily accessible, but when it comes to physical objects, our interaction has been rather limited. SCiO (Latin for “to know”) is trying to bridge the gap and make physical objects just as accessible. This small USB-sized scanner analyzes the nutritional and chemical make-up of foods, pharmaceuticals, materials and plants, and displays the information directly on your smartphone. Using a cloud-based database, SCiO – created by the Israeli startup Consumer Physics – is now aspiring to become the Google of our physical environment.

SCiO: the flash-drive-size scanner’s shining light relays the object’s unique molecular signature back to your smartphone (Photo: Consumer Physics)

So, how does it actually work? By pointing the device at an object, a light shining causes the object’s molecules to vibrate. As each molecule vibrates in a unique way, it creates its own molecular signature, which is reflected back via Bluetooth to your smartphone app. Using an algorithm, the app then compares the data to the cloud-based database, and displays the object’s chemical/nutritional breakdown immediately on your screen. At $249 per unit, SCiO is now making this technology – which has previously been pricy and mainly available at scientific labs – accessible to the general public.

In May 2014, SCiO launched a Kickstarter campaign which was literally an overnight success, exceeding its original $200,000 goal within the first 24 hours, and raising over $2.7 million. The first SCiO scanners will be shipping to Kickstarter backers in December 2014, but the Kickstarter campaign wasn’t only intended to raise funding but rather and foremost to expand SCiO’s database using crowdsourcing. With SCiO’s open API policy, early adopters and third-party developers can sample additional objects to extend its database listings, and also create new apps and add-ons.

While SCiO does have its margin of error – partial sampling (small-scale/short-depth), protein-detections difficulties and complex object-database comparison process – this device may not just improve quality of lives but essentially help save lives. Sure SCiO can help one chose a ripe avocado or let users know how many calories are in their favorite dessert (though sometimes ignorance is bliss…), but detecting contents can also significantly assist people with food intolerances or chemical sensitivity. Moreover, in major regions in Africa, for example – where by 2015 more people will have mobile network access than access to electricity (the ‘off-grid, on-Net’ population) (Rao 11) – SCiO can make life-changing information accessible, by allowing users to easily identify drinkable water sources or detect counterfeit prescription drugs. As technology advances, SCiO and other future molecular scanners may potentially offer medical-related access, by scanning human tissues or blood samples.

With the intent of eventually being embedded in smartphones and smartwatches, SCiO’s stated goal of creating the world’s largest database of fingerprints for our physical world, may be profound on a much larger scale, namely in relation to the Internet of Things (IoT). IoT refers to internet-connected devices in various fields – from home appliances to pacemakers to traffic control and baby monitors – using advanced technology (such as Radio-Frequency Identification) to remote-control and connect objects.

According to a study by Cisco, there are more objects than people using the internet today, with 6.8 billion people online compared to over 12 billion objects. It is predicted that by 2015 more than 25 billion objects will be internet-connected, with a booming 50 billion internet-connected objects estimated in 2020. IoT is likely to increasingly affect all aspects of life, with sensors that will let us know when to refill our tires or allow us to continuously monitor our blood sugar level. Such technological advances do however come at a cost, especially in regards to users’ privacy (Brown et al 204). As daily lives become more monitored, personal data will be registered, accessible and potentially exposed to information misuse, commercial access and hacking. As devices will increasingly do our thinking for us – giving precise driving directions or indicating when we’re out of milk – individualism and freedom-of-choice may become less coherent (do you actually want more milk? is the suggested route the one you really care to take?).

SCiO and IoS in general have major implications on our lives, creating a more transparent world, with perhaps less ‘secrets and lies’, but arising considerable privacy concerns, which are yet to be addressed. According to the Open Source Sensing Initiative, it is a long impending battle between those using IoT to collect data and those whose information is being collected.

References:

Brown, M. et al, Exploring Interpretations of Data from the Internet of Things in the Home, Interacting with Computers: Special Issue on The Social Implications of Embedded Systems (2013), 25 (3): 204-217.

Rao, M., Mobile Africa Report 2011: Regional Hubs of Excellence and Innovation, Mobile Monday, 2011