The CensorSensor – Revealing Localized Censorship through Interactive Maps: A Maptivist Approach to Corporate and Government Censorship

Almost all countries filter the Internet to varying degrees; anything from illegal downloading to child pornography and from human rights activities to government criticism. Filtering the Internet has a potential to reinforce the hegemonic power structures and to constrain public debate, this is especially true for countries with repressive regimes. These practices force Internet users to self-censor (Warf, 45-8). Internet companies, today, often find themselves required to take down content at the request of local authorities such as courts and law enforcement (Warren).

Corporate strategic goals and the level of transparency on a global scale differ from how Internet corporations act, willingly or under pressure from governments, on a local scale. Companies, such as Google and Facebook, present their platforms as empowering to users by facilitating the free exchange of information (Embley). Yet, these same companies, at the request of governments, block content inside specific countries for violating local laws. The levels of access to the Internet seem to depend strictly on the location of the user.

The CensorSensor is an interactive mapping aggregator which incorporates multiple sources —in order to depict the different levels of content removal per country— and has the potential to reveal the increasing geographical limits of internet access. Its objective is to raise awareness and to provide insight in to what extent Internet corporations remove content under local legislation.

The project combines digital humanities research with activism, by challenging the notion of a global borderless Internet (York) in which everyone who has access to the Internet also has access to the same content and information. Maptivism, which is “the use of digital maps to promote a cause” (Scola), is used here to challenge the power structures that filtering enables. The aim is to provide Internet users with the means to compare and evaluate corporate filtering practices and the level of transparency in the reports these corporations provide.

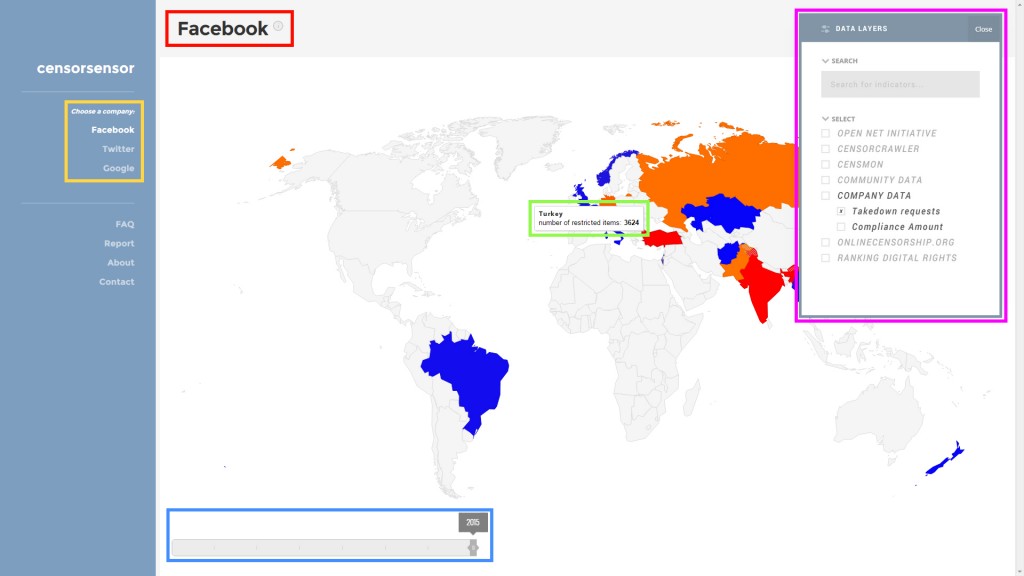

The CensorSensor maps are embedded in an interface that allow users to compare multiple data layers displaying content removal by different platforms [Screenshot 1]. Via a menu system [S1; yellow] users select a platform, for which users can display different data layers [S1; purple] and can select countries to display content filtering information [S1; green]. Information about the data layers can be called upon by selecting the info button [S1; red], and users can browse a timeline that shows how data layers change over time [S1; blue]. Other functionalities includes a short introduction of the workings of the aggregator and a report page [S2], where users can report content removal for improving the “Community Data”-layer [S1, purple 4th layer.]

Screenshot 1: Facebook map functionality

Screenshot 1: Facebook map functionality

The CensorSensor integrates three types of sources in its database. Quantitative data from transparency reports by selected platforms, qualitative data produced via crowdsourcing (submitted personal reports) and automatically generated quantitative data from filtering-detection software applications. The juxtaposition of data from the transparency reports, the community and the automated software is necessary to ensure the validity of censorship claims. These three methods of collecting data have been used by other projects related to Internet filtering but never combined together. The three of them combined overcome most of the limitations of the individual methods and more importantly enable a broader view of Internet filtering practices.

The spectrum of platforms and countries that the CensorSensor examines is narrow, since we have a limited amount of resources and time. Thus, the project focus on the transparency reports of three of the biggest and well known Western platforms: Facebook, Twitter and Google and integrates the data on requests for content removal- and compliance rate per country for these platforms, if available.

The CensorSensor engages with the public and academic debate that critiques the so-called ‘open’ Internet: the idea that information on the Internet is easily accessible for every user. But the dogma of inherent openness, which seems “beyond disagreement and scrutiny” (Tkacz, 1), is highly questionable. This we concluded from our preliminary findings on content removal requests. As the CensorSensor shows access to information differs per country. It is a highly geopolitical space rather than an open one.

The reports

We used indicator F7, as developed by Ranking Digital Rights, on data about government requests to remove content, to evaluate the transparency reports. The reports are not comprehensive and levels of transparency vary from one company to another. Facebook is the least transparent, only revealing the number of pieces of content it restricts per country. The company neither provides its compliance rates per country nor the total number of requests received. Google breaks down the number of requests per reason, something Twitter doesn’t do. On the other hand, Twitter lists the number of tweets and accounts withheld per country. Google, however, only gives the number of items requested to be removed, but not those eventually affected.

Country case studies

We studied data provided by Google, Twitter and Facebook on Germany, the Netherlands, Russia, Turkey, the USA, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia.

At the request of local authorities companies can take down content if it is in violation of local legislation, such as laws banning Holocaust denial in Germany or drug use in Russia. However, for these companies to comply with local laws also means that they are sometimes under the obligation to restrict legitimate speech under international standards, in particular the International Covenant on Political and Civil Rights, at the request of undemocratic governments. For example, between January and June 2014, Facebook restricted seven pieces of content inside Saudi Arabia under local laws prohibiting criticism of the royal family there.

‘Not free countries’

We also studied the reports to see if there is a link between a government’s internet filtering policies and the number of requests it makes. We found out that the 15 countries listed as ‘not free’ by Freedom on the Net’s 2014 report made few to no requests at all. For instance, only two of these countries made requests to Twitter in 2014. They are the UAE and Pakistan which respectively made one and 16 requests. This could be explained by the fact that these countries have repressive legal and institutional apparatuses in place that allow them to filter the Internet without resorting to companies.

We can conclude that Internet corporations’ compliance with content removal requests under local legislation that violates international free speech standards undermines users’ access to an increasingly geopoliticized ‘open’ web.

Bibliography

Embley, Jochan. ‘Google Unveils New Technology to Protect Free Speech on the Web’. 2013. The Independent. N.p., n.d. Web. 16 Oct. 2015. <http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/gadgets-and-tech/news/google-unveils-new-technology-to-protect-free-speech-on-the-web-8896661.html>.

Facebook. 2015. Government Requests Report. 16 October 2015. <https://govtrequests.facebook.com/>.

Freedom House. Freedom on the Net Report, 2014 edition. 16 October 2015. <https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/freedom-net-2014>.

Google Transparency Report. Government requests to remove content. 16 October 2015. <http://www.google.com/transparencyreport/removals/government/?hl=en>.

Ingram, Mathew. ‘Like Democracy, the Web Needs to Be Defended, Its Creator Says’. N.p., 19 Nov. 2010. Web. 16 Oct. 2015. <https://gigaom.com/2010/11/19/like-democracy-the-web-needs-to-be-defended-its-creator-says/>.

Palfrey, John, and Jonathan Zittrain. ‘Internet Filtering: The Politics and Mechanisms of Control’. Access Denied: The Practice and Policy of Global Internet Filtering. London, England: MIT Press, 2008. 29–56. Print.

Ranking Digital Rights. 2015 indicators. 16 October 2015. <https://rankingdigitalrights.org/project-documents/2015-indicators/>.

Scola, Nancy. ‘Digital Mappers Plot the Future of Maptivism’. TechPresident. N.p., n.d. Web. 16 Oct. 2015. <http://techpresident.com/blog-entry/digital-mappers-plot-future-maptivism-0>.

Tkacz, Nathaniel. ‘From Open Source to Open Government: A Critique of Open Politics’. Ephemera: Theory and Politics in Organization 12.4 (2012): 386–405. Print.

United Nations. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. 1966.

Warren, Tom. ‘Facebook and Google Forced to Remove Content Deemed Offensive in India’. The Verge. N.p., n.d. Web. 16 Oct. 2015. <http://www.theverge.com/web/2012/2/6/2774832/facebook-google-remove-content-india>.

York, Jillian C. ‘The Myth of a Borderless Internet’. The Atlantic 3 June 2015. The Atlantic. Web. 16 Oct. 2015. <http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/06/the-myth-of-a-borderless-internet/394670/>.

Twitter Transparency Report. 2015. Removal Requests. 16 October 2015. <https://transparency.twitter.com/removal-requests/2015/jan-jun>.