Advertiser-friendly vs. Youtuber-friendly: who does YouTube really care about?

In the Internet age, while some companies choose to be LGBT-friendly, eco-friendly or even vegan-friendly, YouTube is openly advertiser-friendly. The de facto standard video-hosting website of the western world has become a staple of our modern society – an overhaul of the way we consume video media. For a time it seemed that everything that could be written and analysed about YouTube had been done, but in September 2016 furor amongst the YouTube community over policy changes, resulting in an unexpected wave of demonetization, has reignited the conversation and begs the question whether YouTube is all that different to broadcast television. Although the discussion sparked and faded out rather quickly, it revealed a disconnect between YouTube as a community and YouTube, the profit-seeking organization.

What Is All the Buzz About?

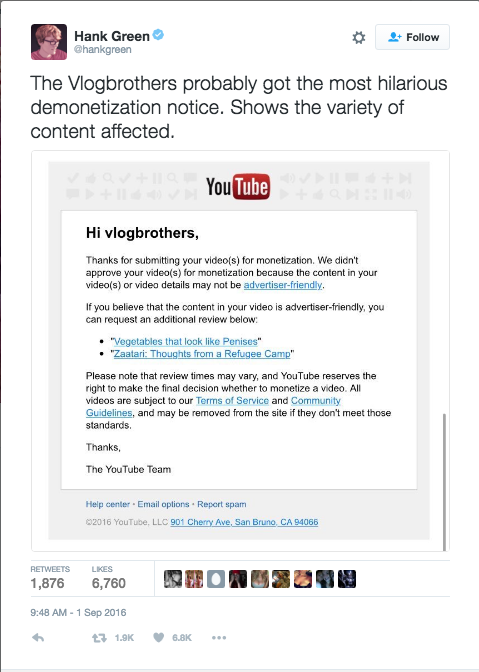

On 1st September, a number of high-profile YouTubers publicly expressed their anger over losing large amounts of revenue due to a violation of the company’s advertiser-friendly policy. It was later revealed by YouTube, in a misjudged attempt to allay criticism, that the policy had been in effect as early as 2012 – changes were instead made to the notification system for YouTubers to track and appeal demonetization, which for some content creators effectively amounts to four years of doctored pay slips. The policy itself emphasises a number of topics that are not all-audience appropriate and therefore not ad-friendly, which includes sexually suggestive content or humour, inappropriate language, and contentiously, ‘controversial or sensitive subjects and events, including subjects related to war, political conflicts, natural disasters and tragedies, even if graphic imagery is not shown’ (YouTube Help). Many YouTubers have pointed out that because the policy is enforced algorithmically, it is often inaccurate, relying on metadata that doesn’t necessarily relate to the appropriateness of the video (Image 1). Even though it is now easier for them to appeal demonetisation, the process is still ‘tedious and time-consuming’ (Kain).

Different Kind of Censorship

This whole situation quite openly suggests that advertisers have become a very influential power in YouTube. Advertisers have the tools to access a variety of information on different Youtube channels such as ‘audience demographics, topics, category and content appropriatenes’ (YouTube Help), and furthermore can appeal to have all ads, even those that are not their own, removed from any video. It is no secret that for many content creators, YouTube ad revenue is their main source of income. An ad-friendly policy that’s dogmatic about being all-audience appropriate affects many styles of video production. Indeed, two-thirds of YouTube users are aged 18-34 (Dehghani et al 165) therefore a number of YouTubers have built their channel on this specific demographic. The ‘wild west’ side of YouTube is what made the platform and some of its content producers so popular and counter-cultural, as an alternative to safe, mass-appeal broadcast television.

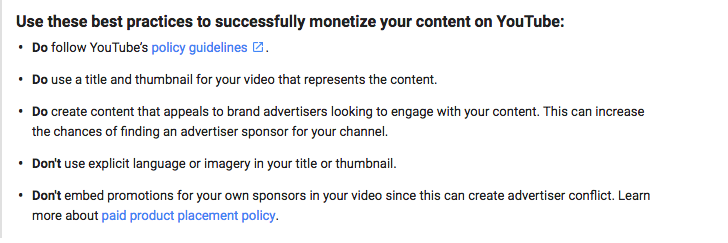

Consequently, we may begin to see self-censorship and self-regulation. It’s not just the probability of losing revenue, but the time-consuming process of appealing mistakenly demonetized videos that is likely to affect content. Though not direct censorship, this is rather what Foucault describes as productive power. Rather than forbidding the creation of certain content, YouTubers are advised methods of assuring success and revenue (Image 2). This process does not even need to be constantly supervised, as long as there is ‘a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures the automatic functioning of power’ (Foucault 201). In this way subjects eventually learn self-regulation and self-discipline.

The Real Value of Community

YouTube is a private, business-oriented company and therefore is free to make these decisions and prioritise advertisers – the main source of their profit. On the other hand ‘YouTube is a platform for, and an aggregator of, content, but it is not a content producer itself’ (Burgess and Green 4). Even though the corporation does not get any direct revenue from the YouTubers and video producers, it would not be able to function without them. Some scholars go as far as calling this kind of commodification of audience/users’ labour as exploitation (Fisher 51). It’s vital for YouTube to make sure its’ content producers cooperate with the corporation itself and various efforts to achieve that can be seen in YouTube’s rhetoric on platform’s community. The great example of this is the launch of YouTube Community, which aims (according to the official announcement) ‘to help strengthen the bond between you and your viewers’ (McEvoy). The tone and vocabulary used points to the idyllic image of YouTube as a family. But while this project is keeping the YouTubers happy and satisfied, there are many other possible gains, that were not so articulated. For example as the users will spend more time communicating on the platform, there will be more time spend interacting with adverts and therefore – greater opportunities for advertising and ad revenues.

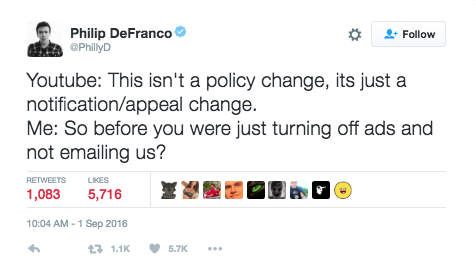

Image 3. YouTuber Philip DeFranco reacting to the controversy

The recent debate on the advertiser-friendly policies and the controversy of demonetization just proved something many were already suspicious about – YouTube’s rhetoric about community and family does not reflect the corporation’s actual priorities. The prioritization of advertiser’s needs rather than the platform’s content producers’ work and execution of power which leads to a specific forms of censorship are worrying practices that are highly affecting and shaping new media environment and community.

Bibliography

Burgess, Jean, and Green, Joshua. YouTube: Online Video and Participatory Culture. Cambridge, Malden: Polity Press, 2009

DeFranco, Philip. ‘YouTube Is Shutting Down My Channel and I’m Not Sure What To Do.’ YouTube. 31 August 2016. 17 September 2016. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gbph5or0NuM>.

Dehghani, Milad, et al. ‘Evaluating the influence of YouTube advertising for attraction of young customers.’ Computers in Human Behavior 59 (2016): 165-172

Fisher, Eran. ‘’You Media’: Audiencing As Marketing in Social Media.’ Media, Culture & Society. 37.1 (2015): 50-67

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish The Birth of the Prison. New York: A Division Of Random House, Inc, 1995

YouTube Help. 2005. YouTube. 17 September 2016. <https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/6162278?hl=en>

Kain, Erik. ‘New ‘Adertiser Friendly’ YouTube Policy Isn’t Actually new, Isn’t Censorsip.’ Forbes. 1 September 2016. 17 September 2016. <http://www.forbes.com/sites/erikkain/2016/09/01/new-advertiser-friendly-youtube-policy-isnt-actually-new-isnt-censorship/#1c528cd22c44>.

McEvoy, Kiley. ‘YouTube Community Goes Beyond Video.’ YouTube Creator Blog. Youtube. 13 September 2016. 17 September 2016. <https://youtube-creators.googleblog.com/2016/09/youtube-community-goes-beyond-video.html>