Squarespace and Interfacification: How Much Does Knowing How to Code Matter Anymore?

In an age of intuitive design and slick interfaces, users nowadays are rarely challenged to question or understand the mechanics underlying digital media.

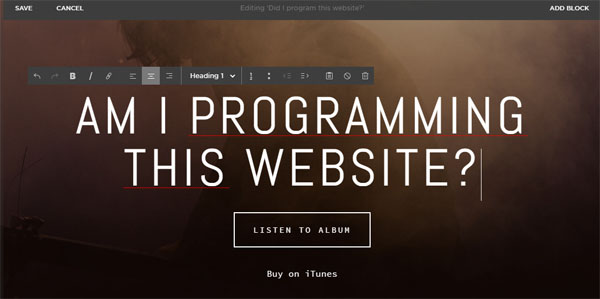

In the early days of computing, one would need basic technical computing skills in order to operate the machines. Since the introduction of Graphical User Interfaces (GUIs), this technical know-how has made way for simple clicking, swiping and tapping. Some argue that this has led to a mindless relationship with digital media, and subsequently understanding coding as a crucial skill in developing thoughtful insights in the techniques underlying these hyper-optimised GUIs. The DIY-website builder Squarespace is a prime example of ‘interfacification’: building a website, normally a HTML, CSS and JavaScript-ridden task, is now possible through a few clicks within Squarespace’s interface. One only has to pick the right template, edit text and drag-and-drop away. In a highly interfaced digital landscape, does it still matter to understand the code running today’s intuitive interfaces?

Squarespace template

While Squarespace is by no means a new platform as it was born 2004, it still shows a rapid increase in users and can therefore be seen as an emerging platform. W3techs reports that at the time of writing the platform hosts 0.5% of all websites, up from 0.3% in September 2015.

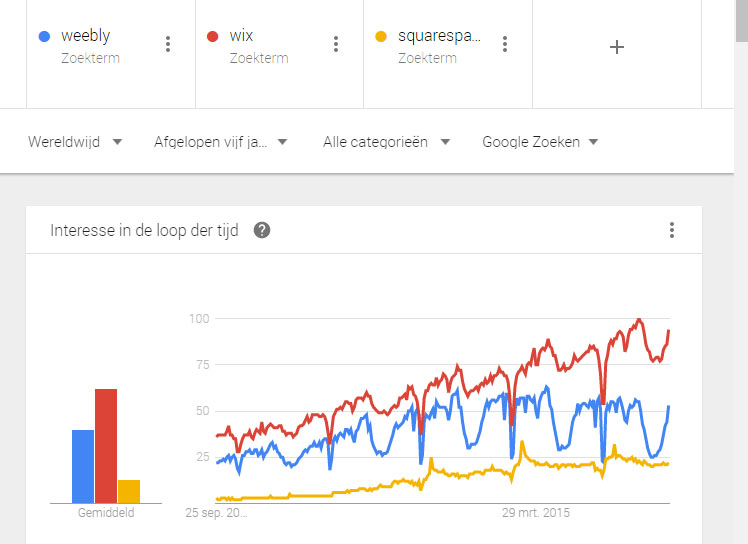

Similar website builders like Weebly and Wix also grow in terms of users, and Google Trends also indicates an increasing interest the services.

But what are the impacts of the rising popularity of easy-to-use website builders on user agency? Should we perceive it as a sign of increased empowerment through DIY-ing, or alternatively, as an opportunity for companies to be the directors of our production of digital media?

To explore this, it is worth questioning what understanding the ‘technical’ aspect of digital media means. ‘Older’ media had users directly interact with the content of the medium – for instance, a photograph was ‘fixed’ on the roll. This way, technology and content were one and the same thing. However, current digital technologies departed from this unification because now software acts as a layer between the content and the technicity of the medium. Media scholar Lev Manovich argues that unless you are a programmer, you rarely deal with the technological complications of a digital medium anymore (2013). Consequently, Manovich thinks of new media as consisting of two layers: the “computer layer” and the “cultural layer”. The former consists of the technicalities such as computer code, which impacts the latter consisting of the ‘cultural logic’ formed by the representation of digital media (2002).

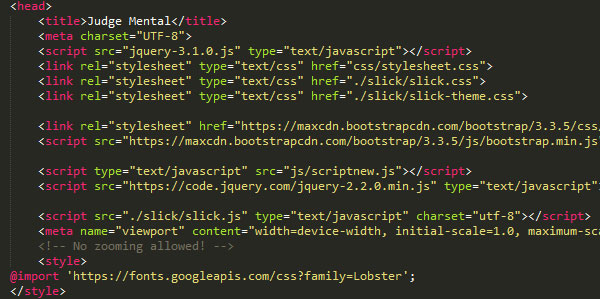

Making a website used to involve at the very least writing HTML code, which can be attributed to engaging with the computer layer. However, sites as Squarespace seem to avoid the computer layer altogether by making content creation possible from the pre-determined and interfaced cultural layer. A possible problem with this is that now the power on the once-neutral web largely shifts to the people or companies designing these web-building interfaces, as they impact how websites are represented and constructed. As Manovich argues, the human perceives digital media through software, and this also means that “they are the result of the particular choices made by individuals, companies and consortiums who develop software” (2013). This is notably the case with Squarespace as the site encourages customers to use one of its templates.

HTML code

Large companies designing the way we produce and consume digital content is what media activist Douglas Rushkoff perceives as a potential danger. He sees harnessing programming skills as an empowerment tool for independence from big corporations. While digital technologies, most prominently the Internet, promised a democratic and highly personalised future, we now are frequently pushed into certain systems and behaviour, he argues. However, the “programming community” avoids this by developing “the most promising challenges to existing centralized powers and financial hierarchies.” (Rushkoff 2010). According to Rushkoff, “in the emerging, highly programmed landscape ahead, you will either create the software or you will be the software. It’s really simple: Program, or be programmed.” (Rushkoff 2010)

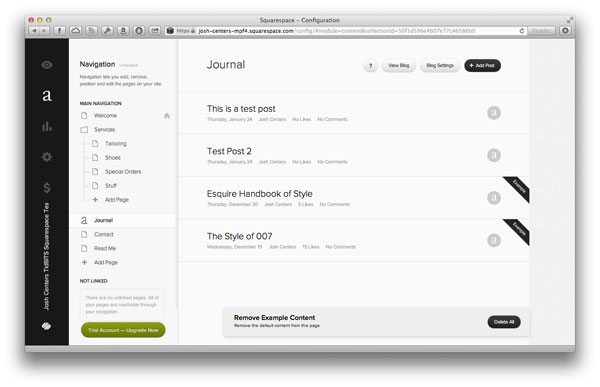

Squarespace back-end

Website builders such as Squarespace raise the question about Rushkoff’s binary opposition between ‘programming’ and ‘being programmed’. On the one hand, the service offers everyone an equal and accessible opportunity to become a content creator without the time-intensive task to master a markup- or programming language. On the other hand, Squarespace directs user behaviour as it lets you pay for using a pre-built template of which users can only edit certain parts. While Squarespace does allow for content creation, it thus does not encourage breaking out of pre-determined barriers outlined by the company. It is therefore highly doubtful that content creation along the lines of Squarespace’s polished web interface fits in with Rushkoff’s idea of empowerment, where users do not have to follow along the lines of big companies (Squarespace consists of 554 employees and powers ‘millions’ of websites). Maybe we should focus less on how easy it is for regular people to create digital content, and more with how we can gain computational knowledge and independence in an age where less and less technical know-how is asked from us. As users, we might have to be critical on how these interfaces direct the way we use digital media, even when they simultaneously imply empowerment in providing an easy gateway to produce our own digital content.

Academic sources

Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media. MIT Press, 2002.

Rushoff, Douglas. Program or Be Programmed: Ten Commands for a Digital Age. Or Books, 2010.

Manovich, Lev. “Media after software.” Journal of Visual Culture, vol. 12 no. 1, 2013, pp. 30-37.