Car Companies Are Racing to the Street with the Self-Driving Car

Autonomous cars are starting to take over our highways faster than you would think. The notion of the self-driving car is a big deal in media and debate as of late. Many car companies are eager to become the market leaders in this new technology. These driverless cars are supposed to make our lives easier and safer by taking over the activity of driving. According to Google, even aging and visually impaired loved ones will be able to drive around independently and safely in the near future. The main question that does not seem to be fully addressed by these companies is what will happen when things go wrong?

![]()

First Fatal Car Crash While on Autopilot Mode Was In a Tesla Car

Back in May of 2016, the first known death by a self-driving car happened. Without a doubt, this fatal crash caused many consumers to second-guess the trust they may potentially put into the autonomous vehicle industry. The driver who was killed was in a Tesla Model S on autopilot mode, which controls the car during highway driving (Morris), (Tynan, Dan, and Danny Yadron).

The car’s sensor system failed to distinguish a large white truck against the bright blue sky. When Tesla released a statement regarding that fatal crash they tried to shift the blame of the accident, and said that their autonomous software is designed to “nudge” to keep the drivers hands on the wheel (Mearian), (Tynan, Dan, and Danny Yadron). They go on to say that even though autopilot is getting better all the time, it is not a perfect system and it will still require the driver to remain alert (Morris), (Tynan, Dan, and Danny Yadron).

![]()

Implications of the Fatal Crash

This crash was not only a tragic loss of life, but it also brought to light an array of challenges, ethical questions, and in a way theoretical debates have now become very real (Mearian). It is hard to say who is to “blame” for this crash. Tesla’s Autopilot isn’t perfect, but the bigger picture here is that two humans created a situation that the automated system failed to save them from (Mearian), (Morris).

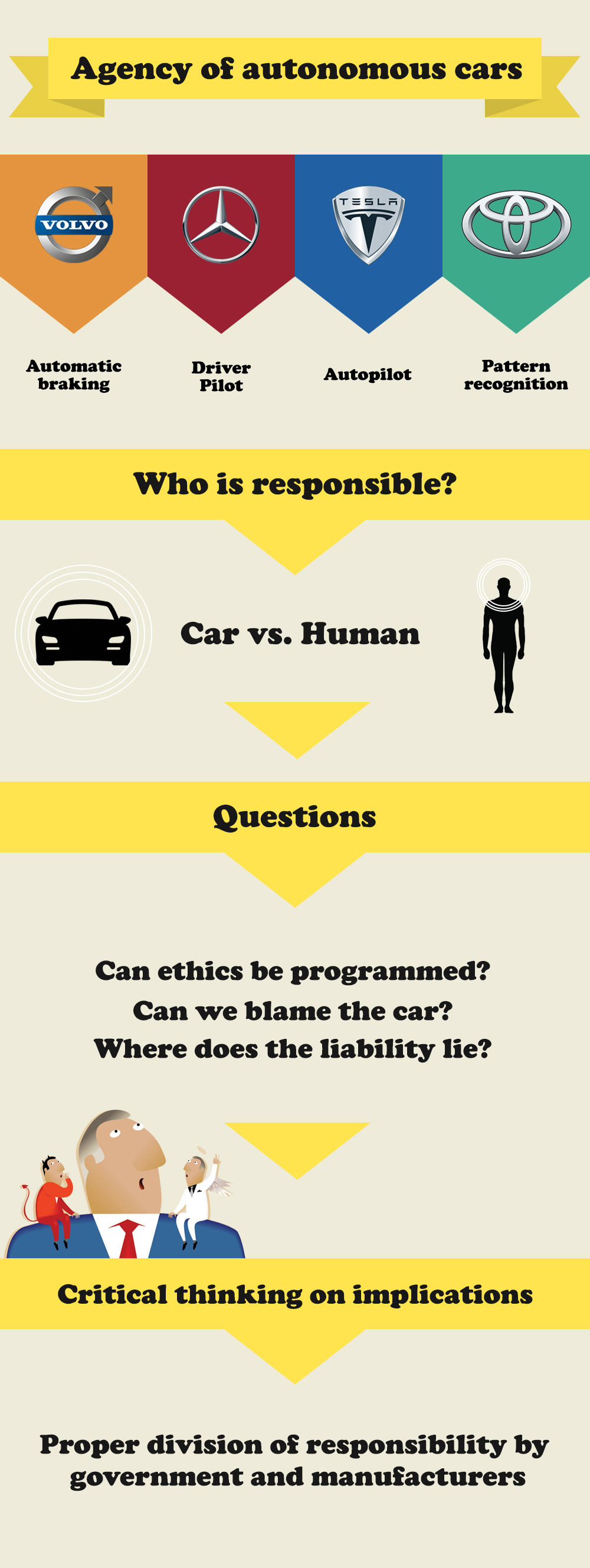

The question with autonomous cars is that of ‘agency’. The word ‘agency’ comes from the Latin word ‘agentia’ which in turn is derived from the verb ‘agere’, meaning ‘to act’ or ‘to do’. In the case of the driverless vehicle, the agency or action is distributed between the car and the human.

Sociologist Bruno Latour states that actions are always dependent on their material context and thus agency is always distributed. Designers can delegate specific responsibilities to an artifact by inscribing them into the design of the object. To illustrate: the speed bump is inscribed with the responsibility to make sure that a driver doesn’t drive too fast (Verbeek, 361-362). As with the example of the speed bump, the driverless car is also delegated by design with certain responsibilities. The most important one too companies and consumers, seems to be driving in a safe way. However, with the notion of autonomous cars this inscription is loaded with a moral dimension.

What exactly the consequences will be are hard to predict, as fully autonomous cars are not embedded in society yet. Therefore, we will look at some of the biggest developers of these cars at the moment, and the current focus of their version of an autonomous car. By doing this we are able to derive the main influences of the current autonomous technologies used in cars, and from there we can provide a basis for thinking about the potential ethical consequences.

![]()

Volvo

In their vision of the Volvo of 2020, Volvo is mostly propagating less stress, less emission and more safety. This is made clear by their slogan: ‘Volvo Cars IntelliSafe: Travel calmer, safer, cleaner.’ They intent to be using radar and cameras to avoid critical traffic situations like crashes. Their car will detect a dangerous situation and brake automatically as a consequence. Lin raises this question: if braking automatically is always the best solution? (74) For example, we need to know how hard the car would need to brake, and how it knows what kind of object is in front of it. For the upcoming years, it seems Volvo will keep focusing on this kind of technical or software based tools, as a transition into possible totally autonomous cars.

Volvo’s IntelliSafe brings up the question with whom the responsibility lies when a crash actually does happen. One could say that the owner of a driverless car cannot be held responsible because the actions do not rely on a user (Duffy, Sophia, and Jamie Patrick Hopkins, 111). With the Volvo IntelliSafe cars this is even more complicated because they can be switched into an autonomous drive-mode. So the question here remains, of whether or not these Volvo IntelliSafe cars can truly be called driverless?

Toyota

Toyota seems to have a similar approach as Volvo. Rather than trying to match the efforts of parties like Google to build fully autonomous cars right away, they also envision drivers and software sharing control over the years to come. Gill Pratt, main researcher of the Toyota Research Institute, names this form of autonomous driving ‘parallel autonomy’. Toyota takes safety as one of their main priorities, especially in regard to software taking over in cases of emergency. Gill Pratt, refers to this as the ‘guardian angel’ approach. For assessing these safety issues, Toyota is looking into prediction software as well as pattern recognition software. This software can for example detect kids who are about to cross the streets while looking at their phones. Pratt mentions how techniques like deep learning could be applied to this combination of parallel autonomy and pattern recognition. This brings up two interesting points regarding ethical consequences of Toyota’s view on autonomous cars.

First, the same as with the Volvo approach, the question arrises who is responsible when a crash happens. In this case however, it’s about software that should recognize danger before it actually is present, instead of responding on it by braking. This might lead to people expecting the car to recognize danger, so that they might be paying less attention to the road, as both drivers or pedestrians. According to Forrest and Konca, “What we consider common sense because everyone has to learn the rules of the road would no longer be known by all people on the road” (48). Secondly, although we might expect technology to behave in a particular way, it’s easy for manufacturers to point out the human as still being responsible, when using a parallel autonomous system. But when this autonomy is improved by adding for example deep learning, as Pratt mentions, or other corrective mechanisms, we could actually be able to blame the car when it’s able to understand its fault and learn from it, “which will prevent an artifactually intelligent autonomous robot/softbot from repeating similar mistakes” (Crnkovic and Çürüklü, 7).

Mercedes-Benz

Mercedes-Benz is the first manufacturer to actually give a statement about the ethical part of their design. They state that their new 2017 E-class will always prioritize the safety of the driver since it’s the only safety they can guarantee. When put to practice this means that when the software has to decide between saving a child on the road by steering into a tree or hit the child in question, the software isn’t going to act (Dogson). This might sound crude but according to Bonnefon, Shariff, and Rahwan, the majority of the people want their car to safe them in case of a crash (1514, 1573). Could this be seen as a sort of discrimination against non-drivers? (Lin, 70-73)

The car of Mercedes is “Luxury in Motion”. When driving a semi-autonomous Mercedes you could switch to Driver-Pilot in situations where driving isn’t much fun, so that the driver will be able to do better things with his or her time.

However as Eric Adams of the magazine Wired found out, the Driver-pilot isn’t perfect. It is supposed to take over the action of driving but in reality he had to take control a couple of time while driving. When questioning Mercedes-Benz about responsibility, they replied that the driver should always be ready to take control. If we were to believe the marketing campaign, autonomous cars would allow us to do different activities while driving. They are designed to take over the action of driving but when it comes to liability, the human is still responsible. As Sophia Duffy and Jamie Patrick Hopkins question: is it morally permissible to impose liability on the user based on the duty to pay attention to the road to intervene if necessary? (629)

Tesla

Many cars on the market are trying their hand at creating the best version of the autonomous car, but without a doubt, Tesla has exposed society to driverless tech the most thus far (Muoio). Tesla is seen as the forerunner in this autonomous vehicle craze because the company for a while now has offered drivers of their car autonomous driving features. Some of these safety features are automatic lane change and collision avoidance. The newest Tesla 8.0 software update is their biggest update yet, and it includes significant updates to their semi-autonomous driving system called ‘Autopilot’ (Muoio). CEO of Tesla, Elon Musk, has even stated that this update will make Tesla cars “three times safer than any other cars on the road” (Muoio), (Thompson).

Tesla 8.0 has improved the accuracy of the Autopilot system by making better use of the radar sensor on their vehicles. Until now, the radar system was always a supplementary sensor, but now it has a greater role in determining if an object is in danger or not (Thompson). The data collected by the improved radar system will also have more weight in deciding how the car should react in Autopilot (Thompson).

Tesla Autonomous Car Illustration

![]()

The focus on safety and its implications

All of the above mentioned companies seem to have safety, in the use of autonomous technologies, as first priority. Also, at this moment, they all seem to be focussing on the current transition fase in between human driving and fully autonomous driving, by slowly applying more and more autonomous technology to a human driven car. The main question that comes forth is that of with whom the responsibility lies. But there are other, smaller questions that come up, and that are part of this bigger notion of responsibility within the shift of agency.

One small question that arises is which ethics are being programmed into the autonomous car to deal with crash scenarios. Mercedes, for example, will always prioritize the safety of the driver even at the cost of pedestrians. This is the most preferred option in this dilemma, because people will not buy a car that would sacrifice themselves. Volvo and Toyota take an approach of preventing accidents, but they do not give a statement about their ethical choices. The same goes for Tesla, which also stays away from giving their opinion about ethical concerns.

All the car producers try to develop a system or software for dealing with dangerous situations. Auto manufactures can implement for example targeting algorithms or crash-optimization algorithms, as we have seen from the four main developers of autonomous cars and their priorities as discussed above. Lin concludes from this that car manufacturers are discriminating in traffic situations: “Somewhat related to the military sense of selecting targets, crash-optimization algorithms may involve the deliberate and systematic discrimination of, say, large vehicles or Volvos to collide into” (73). A question of concern is: can we let programmers make such decisions? These kind of questions contain judgements about ethics and are difficult to approach.

Another question concerns the liability of autonomous cars. Especially, because according to these car companies, the driver is still responsible for paying attention, even though they are encouraged through marketing to relax and let the car do the work. But when we rely on this system to keep us safe, who is responsible when a crash does happen? Can the driver be held responsible for paying attention while the responsibility of driving is delegated elsewhere. According to Duffy, Sophia, and Jamie Patrick Hopkins: “Existing laws governing vehicles and computers do not provide a means to assess liability for autonomous cars” (123).

These are all questions that the car developers should take into account when designing fully autonomous cars. Just as much and perhaps even more when developing autonomous technology that is added onto human-driven cars. When the moment comes that we as humans have totally no part in driving at all, it might perhaps easier to just blame the car or manufacturer when things go wrong. But it seems the current status of shared agency actually creates more ethical questions to take into account then a status of fully autonomous cars would. The critical thinking on the ethical implications of autonomous software, should push car manufactures and the government in the right direction, one that is truly the best for the society (Duffy, Sophia, and Jamie Patrick Hopkins 123). This so that the promises on safety made by the car manufactures can become reality, but especially that a proper division of responsibility can be made in a society of distributed agency.

![]()

![]()

![]()

References

Adams, Eric. “Mercedes’s New E-Class Kinda Drives Itself – And It’s Kinda Confusing.” Wired. 2016. 27 June 2016. <https://www.wired.com/2016/06/mercedess-new-e-class-kinda-drives-kinda- confusing>.

Anders, George. “Toyota Makes a U-Turn on Autonomous Cars”. MIT Technology Review. 2016. 21 June 2016. <https://www.technologyreview.com/s/601504/toyota-makes-a-u-turn-on-autonomous-cars/>.

Bonnefon, Jean-François, Azim Shariff, and Iyad Rahwan. “The Social Dilemma of Autonomous Vehicles.” Science 352.6293 (2016): 1573-1576.

CB Insights Blog. “33 Corporations Working On Autonomous Vehicles.” CB Insights. 2016. 11 August 2016. <https://www.cbinsights.com/blog/autonomous-driverless-vehicles-corporations-list/>.

Dictionary. Dictionary.com, LLC. <http://www.dictionary.com/browse/agency>.

Dogson, Lindsay. “Why Mercedes plans to let its self-driving cars kill pedestrians in dicey situations.” Business Insider Nederland. 2016. 12 October 2016. <https://www.businessinsider.nl/mercedes-benz-self-driving-cars-programmed-save-driver-2016-10/?international=true&r=UK>.

Duffy, Sophia, and Jamie Patrick Hopkins. “Sit, Stay, Drive: The Future of Autonomous Car Liability.” SMU Sci. & Tech. Law Rev 16.101 (Winter 2013): 101-123.

Goodall, Noah J. “Machine Ethics and Automated Vehicles.” Road Vehicle Automation. Springer International Publishing, 2014. 93-102.

Hevelke, Alexander, and Julian Nida-Rümelin. “Responsibility for Crashes of Autonomous Vehicles: an Ethical Analysis.” Science and Engineering Ethics 21.3 (2015): 619-630.

Lin, Patrick. “Why Ethics Matters for Autonomous Cars.” Autonomous Driving. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2016. 69-85.

Mercedes-Benz. Mercedes-Benz. <https://www.mercedes-benz.com/en/mercedes-benz/innovation/research-vehicle-f-015-luxury-in-motion/>.

Morris, Z David. “What Tesla’s Fatal Crash Means for the Path to Driverless Cars.” Fourtune. 2016. 3 July 2016. <http://fortune.com/2016/07/03/teslas-fatal-crash-implications/>.

Muoio, Danielle. “After Riding in Uber’s Self-Driving Car, I Think Tesla Will Have Some Serious Competition.” Business Insider. 2016. 9 October 2016. <http://www.businessinsider.com/teslas-biggest-competitor-with-driverless-tech-is-uber-2016-9?international=true&r=US&IR=T>.

Takahashi, Dean. “Toyota research chief waxes on how to save 1.2M lives a year with driverless cars”. VentureBeat. 2016. 7 April 2016. <http://venturebeat.com/2016/04/07/toyota-research-chief-waxes-on-how-to-save-1-2m-lives-a-year-with-driverless-cars/>.

Thompson, Cadie. “Elon Musk Just Announced Big Improvements Coming to Autopilot.” Business Insider. 2016. 9 October 2016. <http://www.businessinsider.com/elon-musk-announces-tesla-80-autopilot-update-2016-9?international=true&r=US&IR=T>.

Tynan, Dan, and Danny Yadron. “Tesla Driver Dies In First Fatal Crash While Using Autopilot Mode.” The Guardian. 2016. 15 October 2016. <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/jun/30/tesla-autopilot-death-self-driving-car-elon-musk>.

Verbeek, Peter-Paul. “Morality In Design: Design Ethics and the Morality of Technological Artifacts.” Philosophy and Design. Springer Netherlands, 2008. 91-103.

Volvo Cars. 2016. Volvo Car Corporation. <http://www.volvocars.com/au/about/innovations/intellisafe/autopilot>.