The Swipe Society: Tindoption

Has it ever occurred to you how much of our precious time can be wasted while struggling to create a family or adopt a child? And we don’t blame you, who does not want that picturesque family idylle. At Tindoption we believe that what the humanity needs right now is a simple and easy solution for adoption. Wouldn’t it make the world a better place if both children and parents could be brought together by a simple swipe right on each others’ pictures? We are certain it would, that is why we present to you the Tindoption app. Your future family is just a swipe away!

The Swipe Society

Did you feel there was something a little scary and wrong, but at the same time familiar about this “new app” presentation? Since the launch of Tinder in 2012 we have evidenced increasing popularity of the apps based on the so called swipe interface. Starting with Tinder being one of the most popular dating apps so far and continuing with swipe logic based apps for finding a job, looking for accommodation, choosing baby names, finding friends for your dog, shopping and deciding on what to eat, we see an evidence of the tendency towards the Swipe Society. What we mean by this concept is a society that normalises and chooses to accommodate various topics and notions into the swiping binary of yes (swipe right) and no (swipe left). In a sense, Tinder’s binary mechanism can become ‘a template for a whole way of life’ (Eler and Peyser).

The increasing popularity of the swipe logic (and therefore an increasing number of apps based on the concept) can be explained by two key characteristics: it is efficient and it is fun (David and Cambre). These two characteristics that make the concept of the swipe logic so attractive to users are the same two reasons that critics are concerned about and that problematise the notion of the Swipe Society itself. Can ‘efficient and fun’ be a solution to various complex social or cultural relations such as, for example, politics? Is it really okay to appropriate some composite and sensitive topics into the swiping dichotomy of 0 and 1? As one of the key figures in questioning solutionism and gamification, Evgeny Morozov, would argue – probably not. The author’s argument can be illustrated in a single quote ‘Constructing a world preoccupied only with the most efficient outcomes – rather than with the process through which these outcomes are achieved – is not likely to make them aware of the depth of human passion, dignity and respect’ (234). And indeed the swipe logic in this case represents a ‘tendency to believe a little magic dust can fix any problem’ (Wu).

Even though many could argue that Tinder or other current swiping based apps may not yet reflect Morozov’s concerns, we believe that the popularity of this simple interface is making a normative claim on what a decision making is supposed to look like (Stanfill, 1061). This grammatization of users’ actions (Agre) (swiping left and right) without any room for other choices could result in this swipe model becoming the de-facto decision making model – the Swipe Society that the critics and academic scholars are already concerned with.

To make it clear, it was never our intention to criticise Tinder and its users or to moralize whether the swipe based apps are necessarily right or wrong. We are rather concerned with the somewhat invisible, ‘technological unconscious’ (Thrift) tendency towards the Swipe Society, which is growing due to the normalisation of swipe logic. Instead of blindly agreeing with Morozov’s work we aim to communicate his critical ideas to the population outside the academic fields, the population that normalises ‘swiping’ without realising it. Therefore, this project aims to start a dialogue by simply asking people: should we start problematizing the swipe logic and when should we start to worry about becoming the Swipe Society.

The tool for conversation: Tindoption app

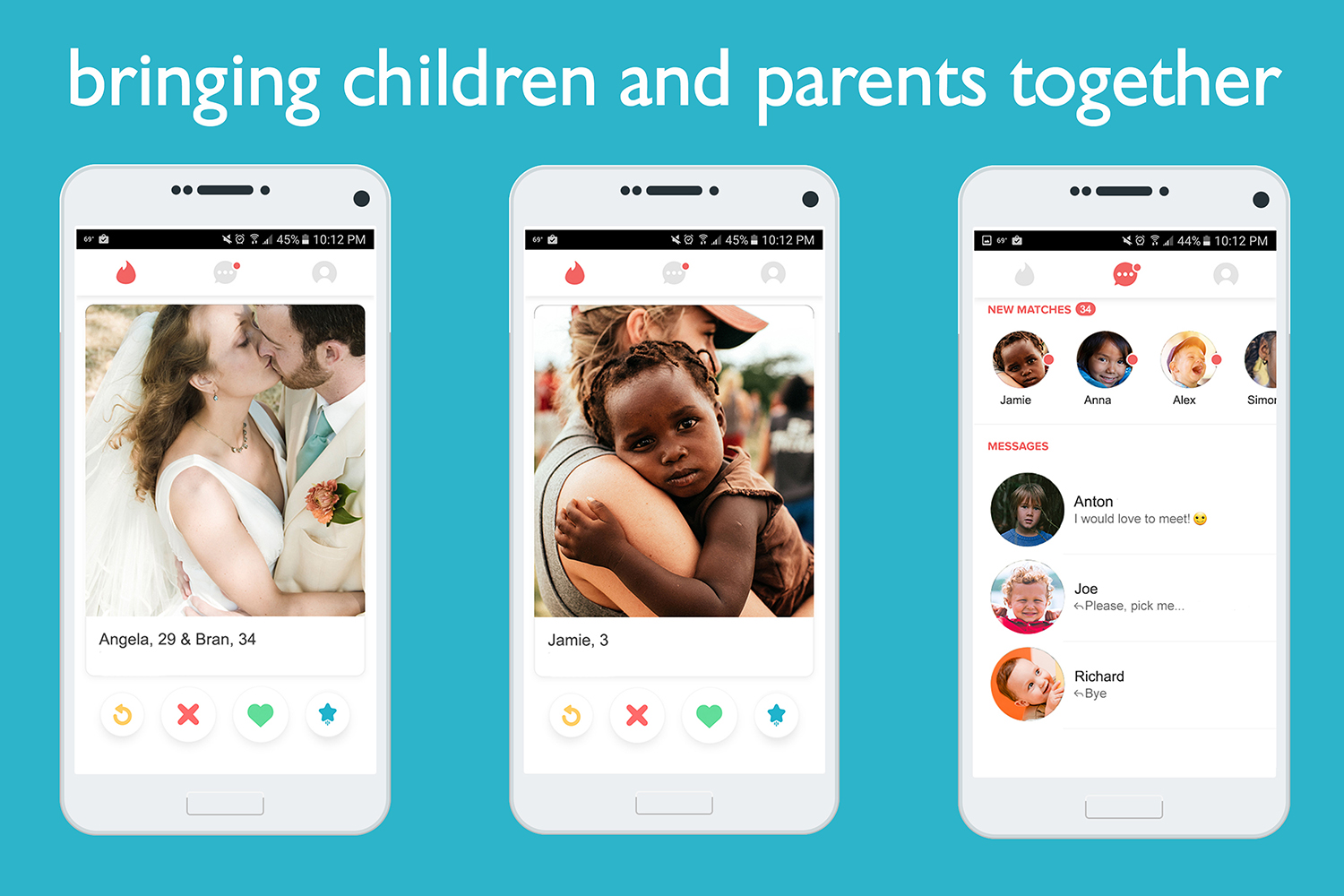

To address these questions to the public, we needed a tool which would allow us to highlight the aspects of the swipe logic that academics are concerned with and evoke people to engage in the discussion. We came up with an idea of a tool which would mildly play on the shock value to trigger critical thinking. And the product of our reasoning was, as you have probably guessed, Tindoption. Tindoption is an imagined app which is based on Tinder interface, but accommodates a new, sensitive and ethically complex topic of children adoption.

Image 1. Swiping pages and a message page

The app would work in the standard Tinder manner: parents go through children’s profiles, swiping right if they like the child, and left – if they are not interested, children do the same with parents’ profiles. If the parent(s) and the child both swipe right – they are matched, so a conversation can be started about meeting up and further adoption process. To visualise our imagined app, we created mock up interfaces: swiping pages for parents and children (Image 1), a messaging page (Image 1), profile pages (Image 2) and a match page (Image 3).

Image 2. Child profile page

Image 3. A match page

As it was mentioned before, we chose to treat Tindoption and its mock up interface as a tool for discussion rather than an actual app that is to be developed. Therefore, we didn’t necessarily go into detail on how the app would function and work in real life, as long as we have the basic understanding which is relevant and interesting while encouraging a conversation (for example we imagine that children would be supervised by an adult while using the app).

Tindoption, therefore, is our way of communicating the possible problematic side of the Swipe Society to the wider public. As a tool, Tindoption does not state what the issues are (if there are any) but encourages viewers to rethink certain aspects of these new media notions for themselves, from their own moral or rational perspectives.

Interviews

To collect data on participants’ reactions and ideas, we conducted eight semi-structured interviews (and three test interviews). This part was essential to the project to see whether Tindoption actually produces reactions and motivates discussion on the topic.

During the interviews the mock up interfaces and description of the app were presented to the interviewees. The questions concerned the use of Tinder, the opinion and problems with Tindoption, ideas about the increasing amount of swipe logic based apps and other. The interviews were treated as ‘a conversation with a purpose’ (Burgess), therefore were open-ended and interviewees could elaborate on the topics they found the most interesting. The research participants were presented with information and consent sheets before the interviews.

Naturally, we encountered some obstacles in this stage of the research. During the test interviews we noticed a tendency of respondents to get defensive because of the belief that Tindoption is mocking Tinder or its users (in some cases, interviewees themselves). As a result of this feedback, a disclaimer was introduced. We are also aware of the rather small sample used for our research, but believe that it provided meaningful insights especially given the restricted time and resources.

Our Findings

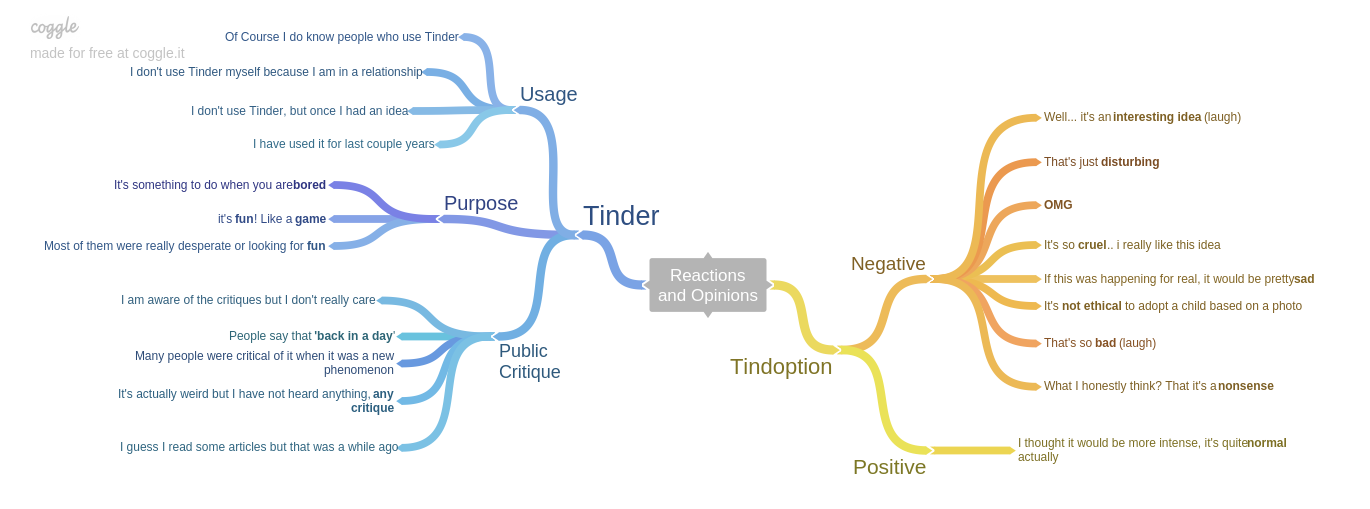

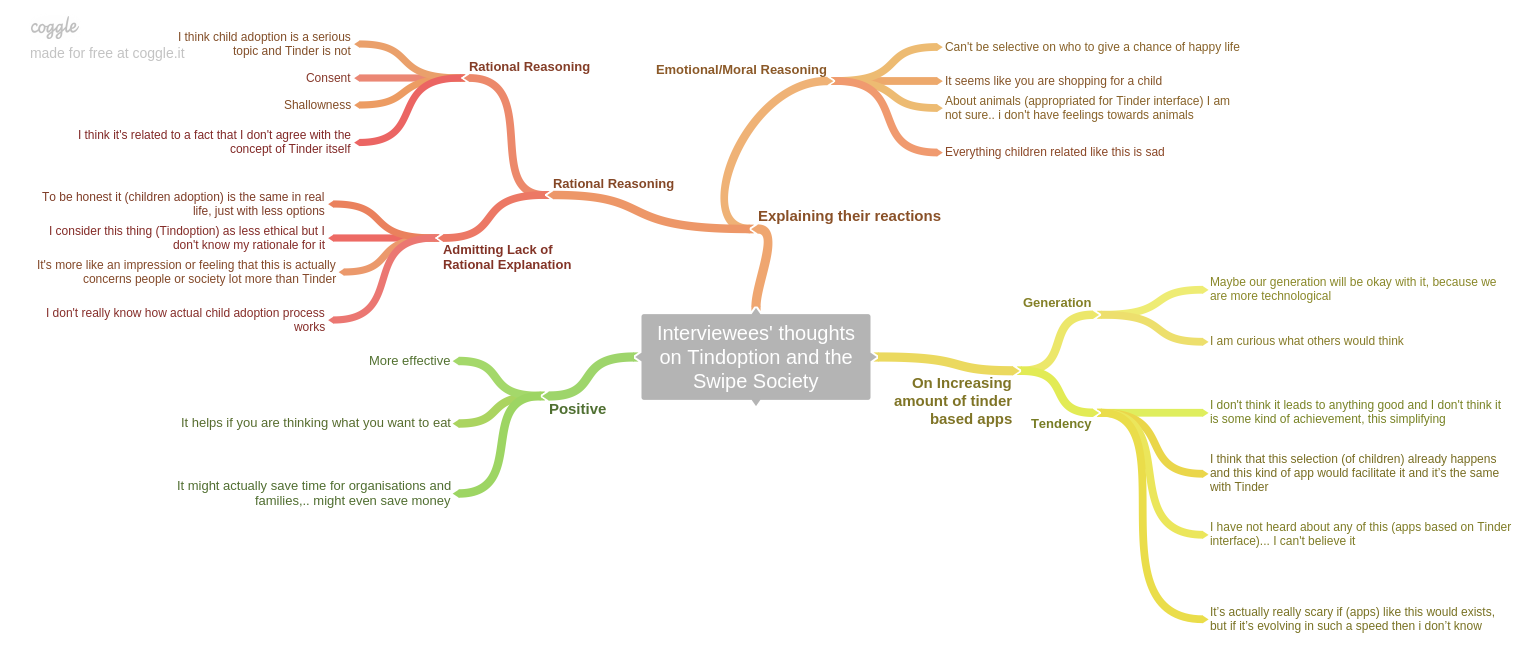

To visualise the analysed data, we created two mind maps representing the main opinions and reactions expressed during the interviews about Tindoption. The first one (Mindmap 1) visualises a significant difference between what people had to say about Tinder and Tindoption. We believe it reflects two major themes on which, our further research was based. Firstly, how normalised Tinder and its use is among our participants. Secondly, how the presentation of Tindoption had a shock value and resulted in interviewees problematising the app. The second mindmap (Mindmap 2) results in various other themes that were coded while analysing the interview transcripts. Some of the most important insights from the qualitative data are explained below.

To start with, majority of the interviewees had a strong feeling that Tinder is more appropriate than Tindoption and tried to explain it via rational reasoning (for example ‘adults can consent, while children cannot’) or moral reasoning (‘it seems like you are shopping for a child’). Though everyone concluded that the increasing number of apps is something to be concerned about and admitted that they have not considered the problematic side of it before they were faced with the ridiculousness of Tindoption.

What is more, at this stage of the research we noticed that interviewees reacted with an emerging concern about the process of children adoption (realising that in reality children adoption is not that different from the basic principle suggested by Tindoption). We realised that Tindoption, even though originally intended as a tool to problematize the increasing popularity of the binary swipe, as a side effect also questioned and challenged the process of children adoption. We, therefore, acknowledge that Tindoption could be used to satirically intervene and engage with the issues related to this topic, but we still choose to concentrate on our initial object – swipe logic.

One interviewee suggested that the selection of children or a date based on looks existed before these apps, but simplified, swiping based apps like Tinder and Tindoption just allow these notions to grow and become a popular norm of our society. We believe this is a very interesting and valid point. The swipe binary based apps such as Tinder or Tindoption, rather than distorting and ‘flattening’ the content, actually just facilitates and enables acceleration of already existing controversial aspects of human behavior.

Despite a number of interesting claims and remarks, it would be inaccurate to draw some certain generalisations and big claims from such a small sample of interviewees. The most important result from the interviews conducted is the realisation that Tindoption does work as a tool to stir up discussion on the normalisation of the swiping interface. The presentation of the app made people problematise, discuss various contemporary notions and bring out the everyday use of new media from the unconscious. Furthermore, the participants enjoyed being involved in the conversations on Tindoption and were happy about the ideas they came up with themselves (which can be seen from the mostly positive feedback).

Where do we go from here?

Due to the positive feedback during the interviews and a lot of encouragement to share our idea with more people, we decided to create a website which presents Tindoption as a real app. Apart from the presentation of the app, the website includes happy customers’ reviews and a comments section for people, who visit the webpage. This allows us to get a larger reach and, therefore, hopefully – a greater number of engagements with the discourse, questioning the notion of the swipe logic. The comment section is of high importance as it allows us to document and track more reactions people have to the app. It is only through the link to the ‘about the project’ section that the visitor is informed that the app is an imaginary one and that it is a product of a students’ project.

Our main concern with the encouragement to share Tindoption publicly was the Tinder copyright laws. To create Tindoption we quite straightforwardly used Tinder interface and the name of our app (Tindoption) has an obvious reference to Tinder itself. We chose to pursue the website despite the concerns by adding the link to the explanation that the app is a satirical/non-profit intervention by a group of students. Moreover, we believe it is unlikely for our project to reach a level of popularity which could attract the attention of Tinder itself. However, in case it does happen, it would result in the project making the statement it wanted to make.

Bibliography

Agre, Philip E. 1994. Surveillance and Capture: Two Models of Privacy. The Information Society 10 (2): 101–127.

Burgess, Robert, G. In the Field: An introduction to Field Research. London, New York: Routledge, 1984

David, Gaby and Cambre, Carolina. ‘Screened Intimacies: Tinder and The Swipe Logic.’ Social Media + Society 2.2 (2016): 1-11

Eler, Alicia and Peyser, Eve. ‘Tinderization of Feeling.’ The New Inquiry. 2016. 23 September 2016. <http://thenewinquiry.com/essays/tinderization-of-feeling/>

Morozov, Evgeny. To Save Everythig, Click Here. The Folly of Technological Solutionism. New York: PublicAffairs, 2013

Stanfill, Mel. ‘The Interface as Discourse: The Production of Norms Through Web Design.’ New Media & Society 17 (7) (2015): 1059-1074

Thrift, Nigel. ‘Remembering the technological Unconscious by Foregrounding Knowledges of Position.’ Environment and Planning D Society and Space 22 (1) (2004): 175-190

Wu, Tim. ‘Book review: ‘To Save Everything, Click Here’ by Evgeny Morozov.’ The Washington Post. 2013. 20 October 2016. <https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/book-review-to-save-everything-click-here-by-evgeny-morozov/2013/04/12/0e82400a-9ac9-11e2-9a79-eb5280c81c63_story.html?utm_term=.d2132817c382>