Authenticating Authenticity: Entrupy’s Use of Crowdsourcing and Data Mining to Authenticating Designer Bags

Alibaba’s Jack Ma caused quite the stir in 2016 when he noted that, “The problem is the fake products today are of better quality and better price than the real names… They are exactly the same factories, exactly the same raw materials but they do not use the names” (“Jack Ma Says Fakes ‘Better Quality”).

While the Internet has allowed luxury brands to reach a bigger audience, it has also paved the way for counterfeiters. In a 2013 study by MarkMonitor, it has noted that there is a “whack-a-mole phenomenon” (“How Fashion and Luxury Brands” 1) among online counterfeiters. Dubious online stores have proliferated on the Internet, and are rarely reprimanded. If one is shut down, another one pops up easily and quickly.

Luxury brands now fight their battles on the World Wide Web. Fashion houses have been cracking down on websites such as eBay and Amazon, stating that such sites allow fake goods to be available, and even profit from such offerings (“Counterfeit.com”; Hays, “Chanel Faces Pushback”).

As counterfeiters become technologically adept at forging and selling luxury goods, several fashion houses have implemented high-tech solutions throughout their creations, to ensure its genuineness and to make it increasingly difficult to imitate.

Luxury brands have employed serial numbers, holographic tags, microprinting, RFID (radio frequency identifier) and NFC (near-field communication) chips, and even fabrics impregnated with radio beacons to guarantee authenticity. Aside from those technologies, some luxury brands also allow their customers to register their products on their official site (Alpeyev, “This Gadget Tells You”; Pike, “Can New Technologies Thwart Counterfeiters”).

Despite these implementations, the fight over fake goods is far from over, as counterfeit technologies are slyly evolving rapidly as well. In addition, for a lot of consumers, detecting the real deal from a knockoff can be perplexing. However, a New York-based startup has created an application that promises to remove the guesswork from determining authenticity.

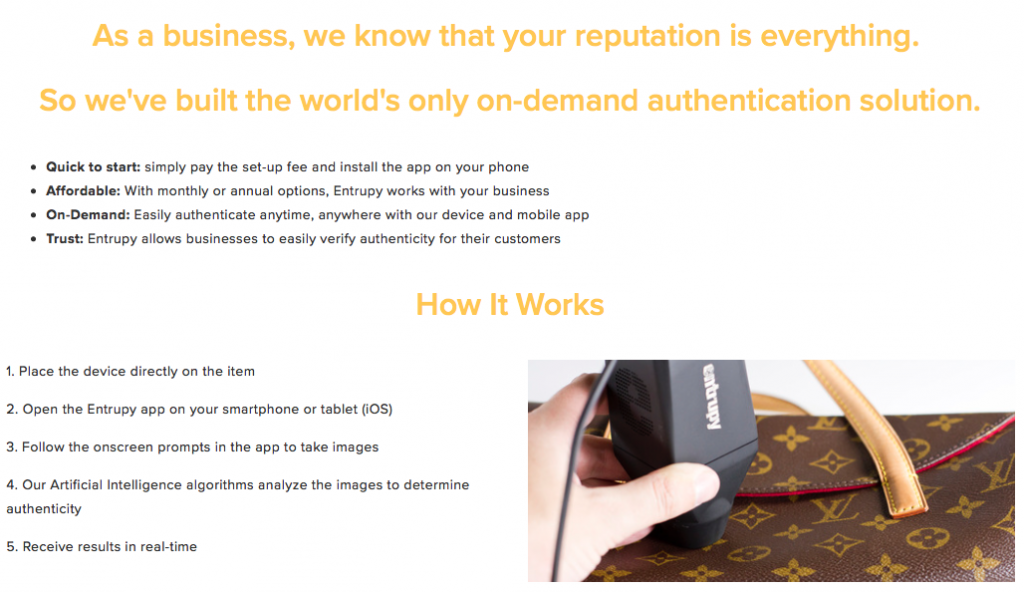

Founded by Vidyuth Srinivasan, Ashlesh Sharma, and Lakshminarayanan Subramanian, Entrupy uses Artificial Intelligence algorithms to detect if a designer bag is real or not. Along with the application, subscribers also receive a camera that can take microscopic images of a bag. Users take images of a bag using the camera, and within seconds, the app determines its authenticity.

Entrupy has a database containing millions of images of designer bags, from which its algorithms base its findings on. Users can also upload images of their own, thus making it smarter (Hargrove, “This App Can Spot A Fake Designer Bag”).

Currently, Entrupy markets itself to businesses, specifically luxury consignment stores, online resellers, and pawnshops. In such business, trust is crucial, as the transactions are of high value. As of now, 160 businesses subscribe to Entrupy (Alpeyev, “This Gadget Tells You”), and according to Entrupy’s official site, they authenticate 11 luxury brands, including Hermes, Chanel, Gucci, and Louis Vuitton.

On their site, Entrupy also clarifies that they are not affiliated or sponsored by any of the brands they validate. According to Alpeyev (“This Gadget Tells You”), fashion powerhouses such as LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton SE also prefer not to associate themselves with second-hand shops.

Noticeably, Entrupy relies on their own database and the images of their users to establish authenticity. While the Entrupy team has dedicated thousands of hours of research and has taken great pains to verify businesses they associate themselves with, can they also establish their own credibility, sans the support of the big brands they authenticate?

Interestingly, Entrupy has taken a Crowdsourcing approach to authenticating goods. Rather than partnering with the brand themselves, the app has relied on their database and input from their subscribers. According to Pickard and Yang, “Crowdsourcing is an inherently social activity” (177). Crowdsourcing has allowed individuals with a common interest or goal to accomplish a task.

In this case, the common task is to authenticate goods. Thus far, Entrupy claims on their site that they have an accuracy rate of 96.4%, and it has been steadily improving. This improvement is likely due its smarter technology, thanks to the growing input from both app and users. This also opens up questions regarding the authenticity and quality of its data.

With regards to Crowdsourcing, it is vital that the contributors belong to the same background, in this circumstance, it is Entrupy interacting with other bag specialists. Crowdsourcing can indeed collect and produce meaningful data and results, but it is necessary that the individuals involved have the same expertise and experience (Azzam and Jacobson 381). It is only then can it be verified that the data received is relevant to the collective aim.

Entrupy is sustained by the efforts of their team and subscribers. To guarantee the efforts of their subscribers, the app also verifies the businesses they associate with, thus, it can be certified that the data being used is of quality and relevance.

Aside from data quality and consistency, Crowdsourcing also touches on Collectivism. When the group has the same concerns and goals, this motivates the individual to contribute due to community involvement and a sense of security towards the community. Thus, this concern is a huge incentive for information exchange (Benbunan-Fich and Koufaris 187).

Seeing as Entrupy and their users have the same objective, and they both receive incentives as business owners in their own right; they are an example of Crowdsourcing’s proper application in business and technological settings.

However, while Crowdsourcing has made data collection easier, and ideas from such have made smart technologies well, smarter, human efforts are not infallible. The gathered data still needs to be scrutinized.

Garrigos-Simon et al. have stated that “Data mining addresses deep information analysis by algorithmic processing to find patterns. Large and medium companies use data mining to sweep through databases and customer feedback in order to adapt their business plans” (301).

Data mining undergoes through the following steps to harvesting data: 1) Data preprocessing, 2) Data processing and modeling, 3) Evaluation, and 4) Visualization (Garrigos-Simon et al., 302-303).

Utilization of data mining allows apps like Entrupy to identify authenticity through the series of images collected. While this ensures consistency and accuracy, the use of data mining opens up issues regarding transparency.

Returning to the matter of brands’ refusal to be associated with resellers and consignment boutiques, plus the fact that the average customer may be confused with detecting the authenticity of luxury goods, how can the businesses that use Entrupy and their customers be sure that they are getting the real deal, and that the information they are getting from the app is reliable?

Kennedy and Moss suggest that data mining should be available as a “common public good,” and that it should also be “regulated by public authorities” (9). In this situation, it may be safe to say that authorities may be the luxury brands themselves. However, those benefiting from the app (both business owner and buyer) should also be aware of the technologies Entrupy uses, and how they gather their data. They cannot be mere users of it, but they have to be involved in every process of detection.

The brands’ rejection of the existence of secondhand stores and resellers may pose as a hindrance to Entrupy’s ability to fully detect the authenticity of bags. This deal then between Entrupy and the businesses that use them must then fully operate on trust and technology.

That may be stating the obvious, but in a business where the commodities are high-priced, and reputations and brand equities are at stake, it is best for Entrupy to associate themselves with other businesses that are deemed trustworthy in their field. Thus, Entrupy’s decision to only transact with other businesses that resell luxury bags.

However, is this not a case of the blind leading the blind if they do not receive the blessing of the brands they authenticate? Although to a certain extent, the availability of Entrupy has empowered customers and given them the knowledge to determine what is genuine and what is counterfeit.

Via crowdsourcing and data mining, it has made verification participatory and precise. Feedback from other specialists gives way to free information dissemination and collaboration. Furthermore, the addition of smart technologies has given structure and substance to the provided information.

While it sounds perfect in theory, in praxis, there is still an unavoidable risk of encountering errors along the way, since the bag manufacturers themselves are not involved in the process of authentication. However, they are united by a common goal: to prevent counterfeits from getting into the hands of customers.

This common goal has paved the way for various technologies to emerge and aid in the fight against counterfeits. While the idea of Entrupy has some loopholes, it cannot be denied that the development of such technologies has opened up the discussion on counterfeits, and through this, concrete steps are being taken to forge the war on fakes.

References:

Staff, WSJ. “Jack Ma Says Fakes “Better Quality and Better Price Than the Real Names.” The Wall Street Journal, Dow Jones & Company, 15 June 2016, blogs.wsj.com/chinarealtime/2016/06/15/jack-ma-says-fakes-better-quality-and-better-price-than-the-real-names/. Accessed 21 Sept. 2017.

“How Fashion and Luxury Brands are Turning the Tide Against Rogue Websites. How Fashion and Luxury Brands are Turning the Tide Against Rogue Websites.” MarkMonitor, 2013. trademarks.thomsonreuters.com/sites/default/files/rsrc_assets/docs/Markmonitor_Fashion_Luxury_WhitePaper.pdf. Accessed 21 Sept. 2017.

“Counterfeit.com.” The Economist, The Economist Newspaper, 30 July 2015, www.economist.com/news/business/21660111-makers-expensive-bags-clothes-and-watches-are-fighting-fakery-courts-battle. Accessed 21 Sept. 2017.

Hays, Kali. “Chanel Faces Pushback in $60M Counterfeit Suit Against Amazon Sellers.” WWD, 28 Apr. 2017, wwd.com/business-news/legal/chanel-faces-pushback-in-60-million-counterfeit-suit-against-amazon-sellers-10877452/. Accessed 22 Sept. 2017.

Alpeyev, Pavel. “This Gadget Tells You If Your Handbag Is a Fake.” Bloomberg.com, Bloomberg, 4 Sept. 2017, www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-09-04/finding-fake-guccis-with-a-smartphone-and-a-microscope. Accessed 21 Sept. 2017.

Pike, Helena. “Can New Technologies Thwart Counterfeiters?” The Business of Fashion, 30 June 2016, www.businessoffashion.com/articles/fashion-tech/can-new-technologies-thwart-luxury-fashion-counterfeiters-rfid-nfc-alibaba. Accessed 23 Sept. 2017.

Hargrove, Channing. “This App Can Spot A Fake Designer Bag.” How To Spot A Fake Designer Bag Entrupy App Gadget, 6 Sept. 2017, www.refinery29.com/2017/09/170961/spot-fake-designer-handbag-app-entrupy. Accessed 22 Sept. 2017.

Pickard, Victor W., and Guobin Yang. Media Activism in the Digital Age. London, Routledge, 2017.

Azzam, Tarek, and Miriam R. Jacobson. “Finding a Comparison Group: Is Online Crowdsourcing a Viable Option?” American Journal of Evaluation, vol. 34, no. 3, 2013, pp. 372–384., doi:10.1177/1098214013490223.

Benbunan‐Fich, Raquel, and Marios Koufaris. “Public contributions to private‐collective systems: the case of social bookmarking.” Internet Research, vol. 23, no. 2, 2013, pp. 183–203., doi:10.1108/10662241311313312.

Garrigos-Simon, Fernando J, et al. “Pervasive information gathering and data mining for efficient business administration.” Journal of Vacation Marketing, vol. 22, no. 4, 2016, pp. 295–306., doi:10.1177/1356766715617219.

Kennedy, Helen, and Giles Moss. “Known or knowing publics? Social media data mining and the question of public agency.” Big Data & Society, vol. 2, no. 2, 20 Oct. 2015, doi:10.1177/2053951715611145.