From Leiden to Livoberezhna: How Memes of a Dutch Statue are Supporting Digital Activism in Ukraine

Introduction: Meeting the Awaiter

As the old adage goes: “love makes you do strange things.” On August 18, love compelled me to cycle for over two hours in the sweltering and sweaty summer heat, from Amsterdam to Leiden University. The reason for my visit? To meet the love of my life: the legendary Awaiter.

Officially named Homunculus Loxodontus, the Awaiter is a “big, cute, partly human and huggable lump” created by Dutch designer Margriet van Breevoort. The statue, according to van Breevoort, was meant to be a “loveable companion” that symbolized medical patients who endlessly “have to await their fate” in hospitals and clinics (Hanly).

The Awaiter in Leiden. (Photo: Hayden Lutek)

Love at first selfie.

(Photo: Hayden Lutek)

Yet over two thousand kilometres east, in Eastern Europe, Homunculus Loxodontus took on a completely different, more politically-charged meaning. Being renamed more affectionately as “Zhdun” or “Pochekun” (which roughly translates to “the one who waits” or “the Awaiter”), edited images of the statue became an overnight social media sensation in early 2017 (Konstantinova).

The reasons for this new found Eastern fame are not hard to understand, especially in Ukraine, which is a country where decades of revolutions have done shockingly little to improve living standards, and society is constantly waiting for the endless promises of the political elite to come true (Keeley).

Thus, this loveable figure struck a particularly familiar chord amongst Ukrainian civil society, with activist Vadim Miskyy explaining that the statue “symbolizes our society’s expectations” after decades of tumultuous political upheaval (Miskyy). Subsequently, “the Awaiter became the hero of dozens of memes” on social networking sites such as Facebook (BBC Russkaya Sluzhba), helping draw comedic attention to everything from delays in visa-free travel agreements to broken promises regarding economic growth.

Yet far from being simply a comical outlet for the expression of political frustrations, the emergence of the Awaiter as a social media phenomenon raises important questions about the role of new media artifacts in the broader formation of contemporary political discourse.

Specifically, it draws attention to how social media users can “memetically make their world” through the production of “linguistic, image, audio, and video texts,” better known here simply as memes, in order to “add [a] democratic voice” to public debates that can then work to resist hegemonic discourses in society (Milner 1-192).

From a “utopian” perspective, this widespread production of intelligent and oppositional memes could act as a platform for grassroots political action that puts “participatory power in the hands of individual users” (Milner 190-191). Such power could then be mobilized to help topple unjust governments and force the redaction of unpopular decisions, thus enabling everyday social media users to easily exert a level of political influence never before thought possible (Milner 190-191).

The world, however, is far from a utopia, and the actual efficacy of memes as a “legitimate form of political engagement” has been seriously questioned by a great number of new media scholars (Halupka 117). Terms such as “clicktivism” (Halupka 116-117) and “slacktivism” take aim at any potential political potency that could arise from digital activism, with many arguing that “symbolic online acts” never could, and never will, truly replace “tried and true forms of collective action” (Kligler-Vilenchik and Thorson 1994-2004).

Consequently, there is an increasingly rigorous academic debate unfolding regarding the true meaning and potential of what Milner has called “memetic participation,” which in this definition includes the production of memes for political purposes (190-192).

In order to better understand and explain this debate, the remainder of this article will be dedicated to looking through the lens of the newly emergent Awaiter, using two specific examples as a case study to help demonstrate how, in more ways than one, digital activism through memes can indeed strengthen and fuel positive developments in civil society.

The Awaiter in Action

Both the memes included below help showcase the positive side of the “memetic participation” debate (Milner 6), demonstrating how “digital activism thrives” and can influence “the public opinion” when it is executed in a clever and intelligent manner (Karatzogianni et al. 105-107).

Yet it is also important to emphasize here that a meme does not necessarily need to manifest sweeping, large-scale physical changes in order to be considered successful or significant. Rather, the mere ability of a meme to act as “an outlet for political deliberation and dissent” is in itself a positive development, helping to potentially nudge society one step closer to implementing true “sociopolitical change” (Karatzogianni et al. 119-120).

The first meme below is a illustrative example of digital activism which is neither revolutionary nor life changing, but nevertheless evolutionary and politically meaningful in the message it delivers. In the meme, we see the Awaiter inconveniencing Kyiv mayor Vitali Klitschko, as the former defiantly blocks the latter from entering a newly ordered bus.

“I am not moving from here.”

(Photo: Facebook.com/Pochekun)

While on the surface such a meme may seem benign, in reality it conveys a powerful message. Specifically, it is poking fun at the Soviet-style way in which the Ukrainian mayor “inspected” a fleet of 50 new buses (24 Kanal). Though Klitschko made it appear as if his presence at the bus yard had some sort of practical purpose, the visit merely served as a media event meant to boost the politician’s image, with photos of the so-called inspection appearing on television (24 Kanal), in newspapers (Segodnya), and in press services (Ukrinform).

The defiant Awaiter in this context humorously displaces and redefines the intent of the mayoral photo op, demonstrating how memes can produce “a new narrative” of an event (Powell 256) that can work to spur a new “conversation between members of [a] participatory digital culture” (Wiggins and Bowers, 1900-1902).

Thus, the meme enables the focus of the story to move from the “mainstream media” narrative of a generous mayor inspecting new buses, to a more counter-hegemonic and “nonconventional” discourse which raises questions about the usefulness of expensive pro-government media events (Karatzogianni et al. 107). Just as the Awaiter disrupted the mayor from boarding the bus, so too does it disrupt our own conventional spoon-fed understanding, challenging us to rethink the standard narrative we were initially supplied with (Powell 256).

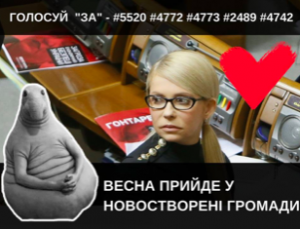

This second set of memes below comes from the personal Facebook page of Ivan Lukerya, a pro-democracy activist who sits on the board of directors of Reanimation Package of Reforms, a popular pro-EU NGO.

(Photo: Facebook.com/Ivan.Lukerya)

(Photo: Facebook.com/Ivan.Lukerya)

(Photo: Facebook.com/Ivan.Lukerya)

(Photo: Facebook.com/Ivan.Lukerya)

(Photo: Facebook.com/Ivan.Lukerya)

Here, the political intent of the meme is much more direct than the previous example: each of the five images calls on a political party to vote “yes” for five specific pieces of pro-reform legislation. In each image, a clever tagline about the legislation is included, as well as a conspicuously placed Awaiter, patiently waiting for members of parliament to make the right decision.

Interestingly, the author of the memes also tagged the official page for each political party in the post, so that their social media team could see both the meme and the reactions it received.

Consequently, this meme functions in a fundamentally different manner than the first, in that it provides a specific call to action (voting in favour of five pieces of legislation) to a specific group of people (members of parliament from five political parties).

Nevertheless, the meme manages to be effective through harnessing the support of a “political advocacy community” in a “digital media environment” (Karpf 9-12), using the popular Awaiter meme to garner likes and comments on the individual images, which will then be widely seen by the actual decision makers tagged in the post.

In this way, this set of memes serves the same function as the once popular email-based “e-petitions,” which attempted to gather digital signatures for particular causes (Karpf 33). Yet here, colourful memes replace lengthy petition emails, and the act of liking and commenting on the images replaces the more arduous process of leaving a digital signature.

Though some scholars may view such a dynamic as problematic, arguing that the “minimal effort” it requires on the part of users means that it is simply “slacktivism” or “clicktivism” (Karpf 9), authors such as Stetka and Mazak argue that “the affordances of social media and Web 2.0,” especially when compared with “Web 1.0,” add nuance to this situation.

Thus, while a simple email-based petition may not have been a particularly potent form of digital activism (Karpf), the multifaceted approach taken by Lukerya above, which mobilizes Web 2.0 affordances like images, tags, likes and comments to garner support for specific and concrete offline initiatives, proves an easy and powerful way to communicate a clear demand to decision makers.

Consequently, though it may not embody the new media “utopia” envisioned by some scholars (Milner 190-191), both examples above help demonstrate how memes of the Awaiter have supported a persuasive and progressive form of digital activism in the Ukrainian context.

Conclusion: Leaving the Awaiter

Though memes of the Awaiter may not provide an instant solution to all of Ukraine’s geopolitical problems, its use as a meme demonstrates how social media users can “create, circulate, and transform” cultural products in order to challenge and redefine mainstream political narratives (Milner 197).

Specifically, the examples highlighted here have attempted to demonstrate how the memes have helped users to “disrupt the hegemonic ideology” of their political culture, while also enabling them to demand “sociopolitical change” from their political leaders directly (Karatzogianni et al. 107-120).

Thus, the cute grey “lump” (Hanly) that is the Awaiter has in many ways allowed Ukrainians to find a new voice on social media, enabling new forms of digital activism that can help support meaningful change in politics and civil society.

Works Cited

Academic

Halupka, Max. “Clicktivism: A Systematic Heuristic.” Policy & Internet, vol. 6, no. 2, 2014, pp. 115-132, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/1944-2866.POI355/abstract. Accessed 19 Sept. 2017.

Karatzogianni, Athina, Galina Miazhevich, and Anastasia Denisova. “A Comparative Cyberconflict Analysis of Digital Activism Across Post-Soviet Countries.” Comparative Sociology, vol. 16, no. 1, 2017, pp. 102-126, http://booksandjournals.brillonline.com/ content/journals/10.1163/15691330-12341415. Accessed 20 Sept. 2017.

Karpf, David. “Online Political Mobilization from the Advocacy Group’s Perspective: Looking Beyond Clicktivism.” Policy & Internet, vol. 2, no. 4, 2010, pp. 7-41, http:// onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.2202/1944-2866.1098/abstract. Accessed 21 Sept. 2017.

Kligler-Vilenchik, Neta, and Kjerstin Thorson. “Good Citizenship as a Frame Contest: Kony2012, Memes, and Critiques of the Networked Citizen.” New Media & Society, vol. 18, no. 9, 2016, pp. 1993-2011, http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/ 10.1177/1461444815575311. Accessed 19 Sept. 2017.

Milner, Ryan. The World Made Meme: Public Conversations and Participatory Media. MIT Press, 2016.

Powell, Alison B. “Network Exceptionalism: Online Action, Discourse and the Opposition to SOPA and ACTA.” Information, Communication & Society, vol. 19, no. 2, 2016, pp. 249-263, http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1061572? tab=permissions&scroll=top&. Accessed 20 Sept. 2017.

Stetka, Vaclav, and Jaromir Mazak. “Whither Slacktivism? Political Engagement and Social Media Use in the 2013 Czech Parliamentary Elections.” Cyberpsychology, vol. 8, no. 3, 2014, https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/dspace-jspui/handle/2134/22390. Accessed 20 Sept. 2017.

Wiggins, Bradley E., and G Bret Bowers. “Memes as Genre: A Structurational Analysis of the Memescape.” New Media & Society, vol. 17, no. 11, 2014, pp. 1886-1906, http:// journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1461444814535194. Accessed 19 Sept. 2017.

Non-Academic

24 Kanal. “50 Новых Автобусов Выйдут Через Неделю на Маршруты в Киеве.” 24TV, http://bit.ly/2xzrpBb. Accessed 20 Sept. 2017.

BBC Russkaya Sluzhba. “Автор Ждуна: Эта Скульптура Изменила Мою Жизнь.” BBC, http://www.bbc.com/russian/features-38881989. Accessed 18 Sept. 2017.

Hanly, Ken. “Dutch Sculpture of Strange Creature a Big Hit in Russia.” Digital Journal, http:// www.digitaljournal.com/news/odd+news/strange-creature-sculpture-in-holland-big-hit- in-russia/article/485579. Accessed 18 Sept. 2017.

Keeley, Sean. “Ukraine Is Still Its Own Worst Enemy.” The American Interest, https://www.the- american-interest.com/2017/08/31/ukraine-still-worst-enemy/. Accessed 18 Sept. 2017.

Konstantinova, Regina. “Dutch Hospital’s Cute Monster Sparks Unexpected Furor in Russia.” Sputnik, https://sputniknews.com/art_living/201702101050553707-zhdun- sculpture-meme. Accessed 18 Sept. 2017.

Miskyy, Vadmin. Personal Interview. 14 Sept. 2017.

Segodnya. “Виталий Кличко: Мы Обновляем Общественный Транспорт Столицы. 50 Новых Автобусов Выйдут за Неделю на Маршруты.” Segodnya Multimedia, http:// kiev.segodnya.ua/kpower/vitaliy-klichko-my-obnovlyaem-obshchestvennyy-transport- stolicy-50-novyh-avtobusov-vyydut-za-nedelyu-na-marshruty-794451.html. Accessed 20 Sept. 2017.

Ukrinform. “В Киеве Через Неделю Выйдут на Маршруты 50 Новых Автобусов.” Ukrinform, https://www.ukrinform.ru/rubric-kyiv/2168418-v-kieve-cerez-nedelu-vyjdut-na- marsruty-50-novyh-avtobusov.html. Accessed 20 Sept. 2017.

Word count (excluding Works Cited section): 1,649