Goalpost in the Ozone: The Deceptively Good Intentions of #Climate

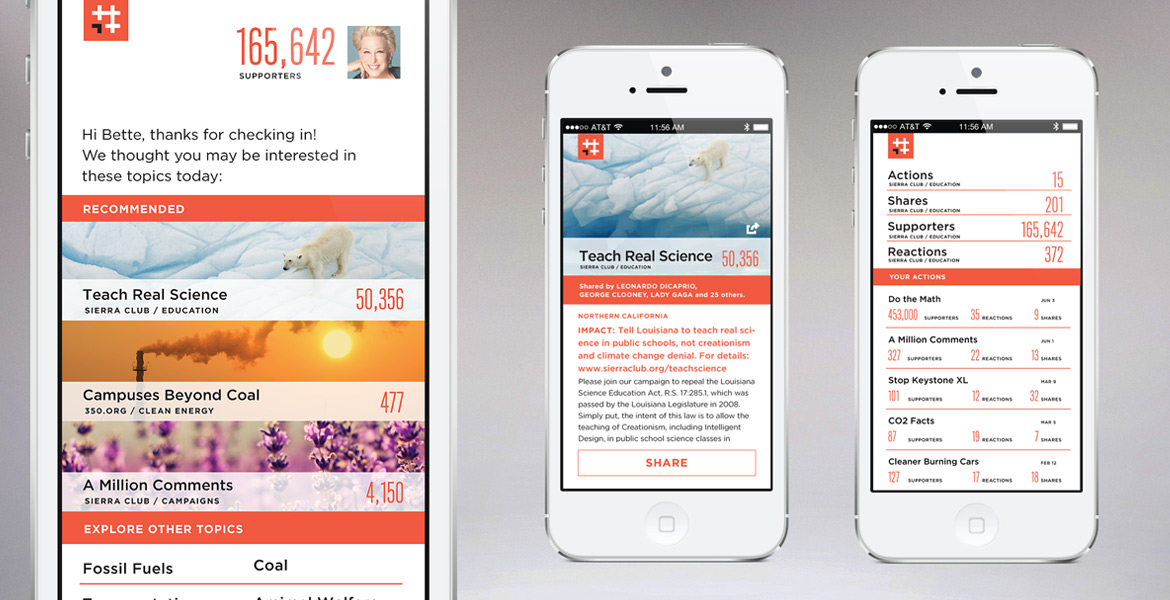

#Climate, as seen by Bette Midler.

As far as scientific consensus goes, it’s tempting to label the ‘debate’ around climate change as being over. However, to do so invites complacency, a willingness to delegate responsibility to a far-off unknown authority. News organisations, politicians and activists are now notorious for their proclivity for catastrophist spins on somewhat oblique facts and figures and committing the paradoxical feat of asserting the topic’s personal relevancy while simultaneously putting the issue at such remove that it can dissipate in an audience’s mind upon arrival. In this article I consider the news aggregator iOS app #Climate, and its drawbacks in attempting to intervene in this tension under new media theories.

App-propriate measures

It is no surprise that analysis of climate change information in new media often portrays the quest as being fruitless, a cul-de-sac of civic engagement where new developments are blithely ignored by bored editors who only see “an increasingly hard subject to sell in much of the media” (Anderson: 168). This leads to an environment where information can be “relatively innocuous in terms of the quality of coverage that is produced, in contexts of political conflict, often complex political ramifications and implications can go unnoticed and unreported” (Finlay: 20). This quote was from an article where Finlay argued in the context of African journalists relying on international wire services and overseas reporting for their work, but it can easily apply to the new media landscape at large as well.

An attempt to ameliorate this situation, tying in to Alex Lockwood’s arguments that audiences are more likely to engage with consumer-generated content (Lockwood: 51) in an effort to amplify their message in a way traditional media does not, climate-change centred apps have been growing in popularity. The advantages at first appear legion – focus on a specific topic allows for greater clarity, the ability to share stories and calls for action are usually built in, and the option for notifications means that the growing developments are never allowed to merely become a buzzing in one’s ear. Although, of course, it must be stated that the reality of that last point is negligible (how many notifications do you get on an average day that you immediately delete and ignore?), the rest are just as rooted in assumptions that threaten to undermine their cause.

I have reviewed a selection of apps tailored to those with a particular interest in climate news stories, taking note of the interactivity apparent in each case and considering them with a new media framework. Among such apps as EarthNow by NASA (a satellite rendering of the globe with points of climate instability marked by red dots, for example hurricanes currently dominating the news) and Skeptical Science (which focuses on the dregs of the climate change debate, addressing common skeptical arguments in a manner that echoes fact-checking sites such as Snopes), the iOS-exclusive app #Climate, launched in 2015, immediately stood out.

#Climate is a news aggregator that connects to the user’s social media profile, offering a tailored experience based on what aspects of climate change policy they happen to be interested in (clean energy, forest conservation, extreme weather, ocean protection, etc.) and collecting stories from a wide variety of news sources, activist organisations and public figures. The app is sleekly designed, and comes with the support of the Sandler Foundation, a philanthropic organisation funded by the founders of the left-leaning nonprofit investigative journalism outlet ProPublica. This combination of technical acumen and admirable political action at first glance works in the app’s favour, but a closer look at the cultivation of incentives on the app raises difficult questions about #Climate’s motivations and effectiveness.

The Cyber House Rules: Affordances as Territory

First, the ability to pinpoint certain “pet” ideas even in an app explicitly designed to stick to one topic, though seemingly innocuous, risks giving the audience explicit permission to compartmentalize the wide-ranging arguments surrounding the topic, creating comfort in their ocean-minded righteousness while setting other views and concerns at the kind of remoteness the app is nominally there to prevent.

Though admittedly a dark interpretation of what is a standard affordance for a news aggregator, a study of inhibitions to behavioural change suggest it’s an inefficient move. Findings by Happer and Philo support the view that the decision to modify behaviour is “led by considerations of cost and convenience” (Happer: 141). A user living in a busy, congested city is likely to filter their experience with the app to prioritize urban sustainability and clean energy over, say, forest conservation. Which would absolutely be their right, of course, but the lack of a corrective in an app explicitly designed to amplify concerns otherwise rarely heard sticks out in its bow to expediency.

I’m here to save the day, please clap.

Furthermore, a closer look at the sources #Climate relies on, while too big to list, includes potentially polarizing outfits such as Greenpeace, The UN Foundation, Amnesty International, U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders, The White House, and, bizarrely, clickbait-centred websites such as Upworthy. While the diversity of approaches is admirable, a focus on authoritative sources ties into another possible behaviour inhibitor: distrust in the decision-makers. It doesn’t take a conspiracy theorist to read ulterior motives into some of these sources (Sanders wanted his progressive base to provide him with votes, The White House is scrambling for legitimacy, Upworthy has a naked ambition for attention that makes Buzzfeed appear modest, etc.), and as shown, when laypeople are faced with the collective achievements made by authority figures on climate issues, “the perceived failure of global and national politicians to act on climate change impacted on their own commitment to do so” (Happer: 142).

Play with me if you want to live

Finally, arguably the most pernicious of the features on the app is the “stats” offered to the user – where one can score “points” every time they share an article on their social media profiles, sign a petition, or encourage another user to sign up to the app’s service. This gamification of civic engagement – converting the desire to do good into the desire to carve ephemeral notches – does nothing to assuage the stereotype of climate activists stifling themselves through self-satisfaction and performative righteousness. A higher score does not do sufficient work in convincing others to do something they don’t want, or have not considered, to do.

Though the features of the app tie in directly to Fogg’s six features of persuasive technology (ie persistence in notification, scale in the hypothetical amount of people one can reach , data management in the large variety of news sources, etc.) the gamification and overcommitment to personalisation present an app more likely to trigger a licensing effect, where I can share an article about clean energy and feel satisfied with my newly gained internet points while a forest burns around me.

Bibliography

#Climate, www.hashtagclimate.org/ (accessed 23/09/2017)

Anderson, Alison. “Media, Politics and Climate Change: Towards A New Research Agenda.” Sociology Compass, vol. 3, no. 2, 2009, pp. 166-182

Finlay, Alan. “Systemic challenges to reporting complexity in journalism: HIV/Aids and climate change in Africa” African Journalism Studies, vol. 33, no. 1, 2012, pp. 15-25

Fogg, B.J. Persuasive Technology: Using Computers to Change What We Think Or Do. Morgan Kaufmann, 2003

Happer, Catherine and Greg Philo. “New approaches to understanding the role of the news media in the formation of public attitudes and behaviours on climate change” European Journal of Communication, vol. 31, no. 2, 2016, pp. 135-151

Lockwood, Alex. “Seeding Doubt: How Sceptics have used New Media to Delay Action on Climate Change.” Geopolitics, History, and International Relations, vol. 2, no. 2, 2010, pp. 136-164

Spartz, James T., Leona Yi-Fan Su, Robert Griffin, Dominique Brossard and Sharon Dunwoody. “YouTube, Social Norms and Perceived Salience of Climate Change in the American Mind.” Environmental Communication, vol. 11, no. 1, 2017, pp. 1-16