iPhone X: The end of privacy?

“The future is here” is a bold statement to make, but it’s one that Apple uses on their website to introduce their latest smartphone

With release scheduled for November, the iPhone X is as provocative as it is luxurious.

offering. The apocalyptically named ‘iPhone X’. It was unveiled this month to a fanfare of technical jargon, excited consumers and concerned privacy activists, but what makes the latest must-have Apple device so provocative?

It’s not the sleek, all-glass facade or the improved 12MP camera. Instead, it’s a fairly well-traveled idea: Facial recognition technology, branded as Face ID.

Whilst this may seem underwhelming, and hardly new, it represents a significant step for a technology powerhouse that sells over 50 million units a year in smartphones alone. Apple’s take on facial recognition technology is a huge leap forward from the poorly-implemented attempts from the likes of rivals Samsung, whose Galaxy S8 device could be ‘tricked’ to be unlocked with a still photograph of someone’s face. Instead, Apple has incorporated cutting-edge infrared light into the front camera of the iPhone X to track over 30,000 unique points on the user’s face, making it far more secure than previous incarnations of the technology.

iPhone X: Stylish and controversial.

Facial recognition technology itself is an intricate, and reassuringly-named, security infrastructure, that draws from the perception that nothing is more secure than our bodies. But what does this mean for the wider debate on privacy and technology? Is the constant gps monitoring, website tracking and constantly learning smart phone now going to use its camera to autonomously decide whether to unlock our phone or not? It appears that the answer is yes.

Yu-Teng Jang discusses the importance of security in smartphones; “Security is a major concern in e-commerce and knowledge economy, a higher level of perceived security leads to higher customer satisfaction and trust… and a higher level of customer satisfaction can eventually create more transaction opportunities and benefits the business” (Jang, Chang and Tsa, 1318). This demand for enhanced security features is a byproduct of the relationship between our personal data and the invisible infrastructures that bind our devices to the vast virtual space where we conduct our daily lives. With an increased willingness to surrender personal data, an increased focus on security is expected in return. It is this reciprocal, intimate, relationship that allows concepts like facial recognition to be spliced with smartphone technology, and furthermore be welcomed.

Face ID is not the first form of biometric security system, and it won’t be the last. It is a natural progression in the evolution of smartphone devices, implementing the latest technology to better protect the increasingly personal information that we store within.

Biometric fingerprint security systems have existed on smartphones for a number of years.

Previously, Apple and other smartphone manufacturers have implemented biometric systems such as fingerprint scanning into their devices, which proved a controversial decision in itself. However, biometric security systems offer an unrivalled level of security as, unlike a passcode or PIN code, they are extremely difficult to hack. In fact, Apple believes the chances of being able to fool their Face ID technology are as little as one in a million. Biometrics are unlike any other security measure: “The strict association between each user and his biometric templates raises concerns on possible uses and abuses of such kind of sensible information.” (Cimato, 98). It is evident that the uniqueness of biometrics is its reliance on our physical data to work, and herein lies the problem. The issue of privacy regarding our biometric information is an alarming one because, as Cimato highlights, we are unable to separate ourselves from it.

Debbie V.S. Kasper identifies three types of privacy invasion; extraction, observation and intrusion, which she details as follows:

Extraction: A deliberate effort to take something from an individual or a group.

Observation: Such invasions involve active and ongoing surveillance of a person or persons; hence, they are not discrete instances, but are ongoing.

Intrusion: Intrusion invasions are marked by the activity of “entering.” This can take place in many ways but generally involves the entry of a presence or interference that is both uninvited and unwelcomed by the persons being invaded.

Facial recognition technology, but in particular Face ID, can fall under each of these categories simultaneously, unlike other biometric technology such as fingerprint scanning. They are applied as thus:

Extraction: FaceID deliberately scans and stores changing information about the user’s face whenever the device is used.

Observation: Face ID, due to it’s very method of operation, is an ongoing method of surveillance. It requires no physical contact to be made with the phone in under for it to activate. The users appearance will have the potential to be streamed alongside data such as location and time.

Intrusion: The device will use Face ID to demand the user presents their face to the camera. By removing the less intrusive biometric fingerprint scanner seen on previous models, Apple is making an informed decision to intrude on the user’s daily life, through forcing the use of FaceID. (Kasper, 76)

If the user grows facial hair or starts wearing glasses, the software understands and learns this information for the future, building a profile of what you look like. This information is a clear embodiment of Kasper’s ideas, and adds weight to the privacy issues that Face ID raises.

Social networks already capture a large amount of our personal and private data.

But, as Susan Corbett details, we already willingly give so much information to third parties; “Social networking sites which facilitate the sharing, copying and re-posting of personal information by other users exemplify both the broader problem of enforceability of individual privacy rights and the more specific problems of the dearth of specific regulation in privacy laws requiring the deletion of personal information.” (Corbett, 254). So really, is there an issue at all?

If users of the iPhone X will also be engaging with social media and synchronising their photo libraries with Facebook or giving Twitter access to their location, does it even make a difference if Apple does retain a library of our facial data? After all, “In this world, privacy is not a static concept, but instead has a dynamic component.” (Papathanassopoulos, 1). Thus, our willingness to share photographs with one third party but not another creates an interesting dynamic. How do we dictate to third parties, particularly those who own numerous media concepts (such as Facebook’s ownership of Instagram and Whatsapp), where the line is when it comes to storing and using our own data?

Consumer credit agency Equifax has had 143 million customer profiles compromised in 2017 due to a security breach, with other huge names such as Ebay and Home Depot all having fallen foul to hackers in recent years. The regularity and scale of these hacks raise serious questions around the security of our data, and whether the third parties we divulge this to are prepared to protect it.

However, even if the data is kept secure and company servers are not breached, to what extent is our biometric data used? Apple reportedly will not have access to the data that Face ID stores, a fact that cannot be applied to government agencies.

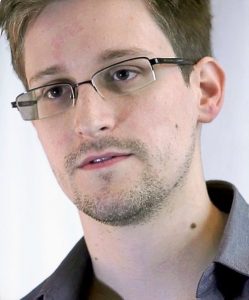

Wikileaks founder Edward Snowden

As the FBI have previously shown in the case of San Bernhadino killer Syed Rizwan Fanook, they are more than willing to try and fight for access to the sensitive security data held on devices. In the aforementioned case, the FBI were unsuccessful in obtaining access to his device through the court process. However, it was a landmark case of its kind. One must stop to examine the potential conflict of principles and morals that would occur should cases like this increase.

Shockingly, the FBI still managed to gain access to the killers iPhone, by employing a third party to hack it.

Even though Apple have been big advocates of customer privacy, particularly with location services, there is little they could do should a government force through a change in legislation. Wikileaks founder Edward Snowden has lifted the lid on the willingness of governments to use mass surveillance on their own citizens, and a device such as the iPhone X is a goldmine for these underhand practices.

The capability for mass surveillance is made frighteningly possible by the iPhone X and Face ID. Previously smartphones held financial and private data, and even scans of our fingerprint. Moving forward, the societal norm will rotate around an expectation to contribute our facial images into a invisible surveillance network, all for using our own smartphones.

Have our devices and their manufacturers fully exploited our obedience of surrendering data?

But most nauseating of all is the last question I will propose:

Do we even have the right to find this intrusive?

References:

Cimato, Stelvio, Roberto Sassi, Fabio Scotti. “Biometrics ansd Privacy”, Recent Patents on Computer Science, vol 1, May 2008, 98

Corbett, Susan. “The Retention of Personal Information Online: A Call for International Regulation of Privacy Law”, Computer Law and Security Review, vol 29, June 2013, 254

Jang, Yu-Teng, Shuchih Ernest Chang and Yi-Jey Tsa. “Smartphone security: understanding smartphone users trust in information security management”, Security and Communication Networks, vol 7, June 2013, 1318

Kasper, Debbie V.S. “The Evolution (or Devolution) of Privacy”, Sociological Forum, vol 20, March 2005, 76

Papathanassopoulos, Stylianos. “Privacy 2.0”, Social Media and Society, April – June 2015, 1