Shiver Me Timbers: Did Streaming Inadvertently Pave the Way For a New Kind of Piracy?

Some time in the mid-2000s, the popular peer-to-peer downloading program E-mule once made me wait for a whole year to download the discography of an Irish blues musician – a hefty file in .rar format, which was owned by only two users across the software’s whole network. I was adamant in enriching my digital music archive so I kept on, and I remember coming home from school and patiently checking on the progress of it every day.

The wait was worth it eventually, but for our modern standards it is inconceivable to be doing that now in the era of “sharing”, where there is more content available than ever – with an equally vast number of methods to access it. As Bob Dylan puts it, things have changed. Although my days as a teenage content pirate are over and I am now a paying subscriber of Spotify and a modest collector of records, the millenial “kids on the block” are keeping the pirate dream alive.

Their modus operandi? Stream ripping, a trend that has grown so exponentially in today’s world, leading to a plethora of questions and complications for all parties involved.

Time flies, technology teleports

Most of the people that are alive today have had the chance to witness the evolution that the internet went through, and one of the milestones in that process was the emergence of the peer-to-peer download software and file sharing services, ranging from the public yet exclusive ones with membership systems (Rapidshare!), to scandalous and independent enterprises (Napster!), through which the way we consumed content started undergoing a tremendous shift.

As a result of that, the content-hungry masses and piracy started going hand in hand, raising all types of moral, financial and ethical concerns along the way. These concerns were temporarily alleviated with the advent of the streaming culture, wherein a means to access larger catalogues instantly was introduced, with different services (such as Netflix and Spotify). But since pirating has also become second nature for a large portion of the public, streaming has become a vital element in this diagram.

The path of least resistance

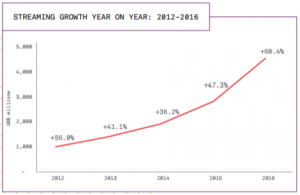

As predicted by Mark Fox in 2002, “streaming media, rather than downloads, [has] become the primary means of delivery for music” [Fox], which can also be said for video content. It really is true, there has been a tremendous increase in the amount of paid subscriptions to streaming services such as Spotify, Apple Music and Pandora between 2012 and 2016 [IFPI, 2016]:

Source: IFPI, 2016

So where does that leave us?

The growth that is outlined here may seem positive, however the truth is different. Looking at the ways through which streaming entered our lives, it is without a doubt that the “cord-cutting” trend that is adopted by the millenial generation is a main element in driving change, and that trend has been on the fast track in terms of being coupled with piracy. Afterall, in the permanently connected, “always on” environment that is taken for granted now, a large portion of consumers choose to take “the path of least resistance”.

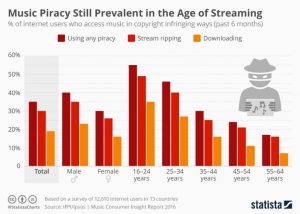

Essentially, piracy can be described as both the “evil twin” and the “angelic other” of copyright, or its “double”, if you will. [Borschke]. People have been pirating content for a long time now, so “the path of least resistance” has always been there, with the demand for immediacy and convenience being on the rise. Therefore, what changed in this equation is not “why” more and more people are pirating content but “how” they are pirating it. In that regard, we meet the term “stream ripping”, which allows users to turn any file that is being played on a streaming platform (YouTube, Spotify, Netflix, HBO GO, you name it) and download it as a file, to be kept permanently and distributed at their leisure. [Savage] According to the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI), “stream ripping is the fastest-growing form of infringement, overtaking other forms of downloading. 3 in 10 (30%) internet users engage in stream ripping, rising to almost half (49%) among 16-24 year-olds.“ [IFPI, 2016]

Looking at these figures, it is safe to say that instead of registering and paying a fixed amount for a service, users choose sources that share stream ripped versions of the content they are after (or stream rip it themselves, for the masses).

Considering the fact that IFPI’s research sample was taken from “84% of the global recorded music market”, namely 13 of the world’s top music markets, the gravity of the situation becomes much clearer:

Source: Statista.com, via IFPI

Appetite for (Creative) Destruction

To look at the big picture, it is also crucial to analyze how this situation took shape. Macromarketing and economics scholar Robert A. Mittelstaedt, in his review of two different books on this phenomenon [Mittelstaedt, 402], describes the blows that the music industry took over the years as “creative destruction” – a fitting phrase, as the industry could not cope with the lightspeed advent of piracy. Another relevant argument made by American academic Lawrence Lessig suggests that “the controversy surrounding piracy was (believed to be) unavoidable given the “nature” of digital technologies. Most thus believed the industry faced a choice: drive digital to the periphery and save the industry, or allow it to become mainstream, and watch the industry fail.” [Lessig, 40]

But it wasn’t so, of course. In truly neoliberal and capitalist fashion, the industry bounced back faster, more pervasively and with more regulations, albeit with difficulties along the way, says industry critic Timothy D. Taylor [Taylor, 2]. The copyright law, which was once “powerless to halt the onslaught of Internet piracy” [Band] is now back with a vengeance. In light of the alarming growth of piracy rates, action is now being taken. For instance, IFPI followed up on their aforementioned report with an update in 2017, stating that “there has been particular focus on illegal content stored on user upload services and in 2016 alone 1.6 million videos and streams were reviewed, with more than 500,000 infringing pieces of content removed.” [IFPI, 2017]

Additionally, in 2016 three major record labels, namely Sony, Warner Brothers and Universal came together in a lawsuit to fight one of the biggest global stream ripping perpetrators, claiming that “tens, or even hundreds, of millions of tracks are illegally copied and distributed by stream ripping services each month and that it’s entirely possible that hundreds of millions, or even billions, of tracks have been illegally downloaded using this method.” [McIntyre]

Guilt-free, record breaking watching habits

While the music industry is still actively trying to come to grips with this pivotal change, the film and television industry is not doing any better. According to a survey conducted by Canadian research firm LaunchLeap (which was ironically also published BitTorrent and file sharing oriented blog Torrentfreak.com), over half of the respondents, namely 53%, admit to using illegal means to stream TV series and movies. The interest in traditional platforms such as TV, DVDs or Blu-Ray is clearly waning, while legal streaming services still hold the lion’s share with 70%. Another surprising find is that out of all the people surveyed, only 7% reported feeling guilty about watching pirated content. [LaunchLeap] A large number of stream rippers also believe that there is little risk associated with the act, with no damage to the artists or content creators in question, not to mention the industry itself.

An almost perfect example of this was observed very recently, when the HBO fantasy show Game of Thrones premiered its seventh season this year. The episode had tremendous popularity not only because it was viewed via official channels 16 million times (a record in HBO’s history), but especially because it was stream ripped and pirated in different ways, which translated into 90 million views globally (six times the official figures of HBO), as reported by the piracy analysis firm MUSO. [Price] Another interesting aspect of this was the fact that 86.56% of the pirated views (roughly 77.9 million times) came in the form of stream ripping:

In an attempt to look at the motivation behind this, UK’s Intellectual Property Office (IPO) conducted a study [Dunn] that shed some light on the precipitous rise of stream ripping and identified some key reasons. In many instances, the musical content was already owned by the user(s) in another format, or they felt that official online music content is overpriced, or needed to listen to music offline or on the move and/or they were unable to afford paying for music. [IPO, 2017]

Alternatively, one could also additionally argue that another main tendency that audiences have is to avoid waiting. When an illegal streaming or stream ripped option (for content that is exclusively available on one platform for paying members, for instance) is made available, it is highly probable that they will want to watch or listen to it right away, rather than waiting for the official release date.

And the stone keeps rolling

In addition to those who are studying this phenomena of stream ripping, there are also those who seek to formulate solutions that are not in the form of lawsuits. For instance, although today’s audience is now more connected than ever to the artists they like or the shows they are fans of, the attempts to offer something more, namely content that is not available in peer-to-peer channels, extras or bundles is seen as one of the more tangible solutions to pave the way for the decline of piracy [Frost].

But in any case, as the internet and the tendencies around it keep evolving, the content consumption culture does too. The financial, social and cultural implications of this phenomenon continue developing with no clear end in sight. Lawsuits and regulations seem to be deterrent to a degree, but the social media fuelled “sharing” philosophy that has taken our contemporary lifestyle by storm is too tenacious a force to withstand, despite the harm that comes with it.

References:

[1] LESSIG, Lawrence Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy, p. 40

https://books.google.nl/books?id=7eRPKIvEo9gC&pg=PT31&hl=tr&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=3#v=onepage&q&f=false

[2] BORSCHKE, Margie. The new romantics: Authenticity, participation and the aesthetics of piracy. First Monday, [S.l.], oct. 2014. ISSN 13960466. Available at: <http://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/5549/4128>. Date accessed: 21 sep. 2017. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.5210/fm.v19i10.5549.

[3] FOX, Mark. Technological and Social Drivers of Change in the Online Music Industry. First Monday, [S.l.], feb. 2002. ISSN 13960466. Available at: <http://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/931/853>. Date accessed: 21 sep. 2017. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.5210/fm.v7i2.931.

[4] MITTELSTAEDT, Robert. Book Review: Steve Knopper, Appetite for Self Destruction: The Spectacular Crash of the Record Industry in the Digital Age – Lawrence Lessig, Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy. Journal of Macromarketing Vol 30, Issue 4, pp. 402 – 405

Available at: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0276146710379418?journalCode=jmka

[5] TAYLOR, Timothy D. Music and Capitalism: A History of the Present, The University of Chicago Press, 2015

ISBN: 022631202X, 9780226312026

[6] BAND, Jonathan. “The Copyright Paradox: Fighting Content Piracy in the Digital Era,” 2001.

Brookings Review, volume 19, number 1, pp. 32-34.

Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-copyright-paradox-fighting-content-piracy-in-the-digital-era

[7] IFPI Music Consumer Insight Report, 2016

Available at: http://www.ifpi.org/downloads/Music-Consumer-Insight-Report-2016.pdf

[8] IFPI Music Consumer Insight Report, 2017

Available at:http://www.ifpi.org/downloads/GMR2017.pdf

[9] Intellectual Property Office – IP Crime and Enforcement Report, 2017

https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/642324/IP_Crime_Report_2016_-_2017.pdf

[10] MCINTYRE, Hugh “What Exactly Is Stream-Ripping, The New Way People Are Stealing Music”

Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/hughmcintyre/2017/08/11/what-exactly-is-stream-ripping-the-new-way-people-are-stealing-music/#439942a81956

[11] FROST, Robert L.. Rearchitecting the music business: Mitigating music piracy by cutting out the record companies.First Monday, [S.l.], aug. 2007. ISSN 13960466. Available at: <http://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/1975/1850>. Date accessed: 21 sep. 2017. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.5210/fm.v12i8.1975.

[12] LAUNCHLEAP, Research on TV Shows and Movies, 2017

Available at: https://torrentfreak.com/images/LaunchLeap_Streaming.pdf

[13] KNOPPER, Steve Appetite for Self Destruction: The Spectacular Crash of the Record Industry in the Digital Age

[14] PRICE, Rob “The ‘Game of Thrones’ season 7 premiere was pirated a staggering 90 million times”

Available at: https://www.businessinsider.nl/game-of-thrones-season-7-episode-1-pirated-90-million-times-muso-2017-7/?international=true&r=UK

[15] SAVAGE, Mark “Stream-ripping is ‘fastest growing’ music piracy”

Available at: http://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-40519137

[16] DUNN, Jeff “The rise of music streaming services hasn’t killed music piracy”

Available at: http://www.businessinsider.com/music-piracy-streaming-chart-2017-4?international=true&r=US&IR=T