“Poop tech is the next big thing” – The Age of Quantified Self Tracking

In the age of the quantified self we are asked to self-track our every mental and physical move to ensure us that we can live to our fullest potential, even if that means we have to track our poop…

Dear Diary…

If people today were to write a diary entry, to log their daily activities it may look something like this: Calories: 2407/Steps: 8,348/ Hours of Sleep: 7,5/Glasses of Water: 8/Units of Alcohol: 2/Current Weight: 67kgs/Days until period: 8/ Amount of times peed: 5/ Rating of poop: 7/10… Yup, looks like an average day of a human being in 2017. To be honest, the list could go on and on, there is a plethora of self-tracking apps out there available to keep track of almost anything in your daily life.

The Cara App

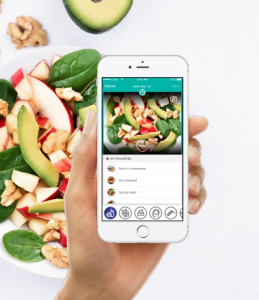

Tracking bowel movements and taking a peek into the toilet before you flush is not all that strange nowadays. “Poop tech is the next big thing” (Henriques, 2017) according to Brinkmann the medical co-founder of the new app called Cara.

The application first launched in the U.S.A. in January 2017, available in the App Store and for Android via Google play. The Cara app was developed by a company named HiDoc, with the incentive to target the large group of the population who suffer from digestive problems, “more than every fifth person on the planet has digestive problems or suffers from chronic digestive diseases” (Cara Fast Facts, 2017) states Cara, the Berlin-based tech start-up. At Cara they found there was not enough sufficient medical support available for these people mainly because there is not a “one size fits all solution” (Cara Fast Facts, 2017). Cara has developed an app that can provide tailor made help with keeping track of your digestive health and can improve it.

How does it work?

The Cara app takes into account that all users are different and that their digestive systems can be affected by a variety of factors, not only the food but also stress and mood levels. Cara is based on an algorithm that connects the different symptoms with certain triggers. The more information the user provides the better the algorithm can link certain triggers to symptoms. (Cara Fast Facts, 2017).

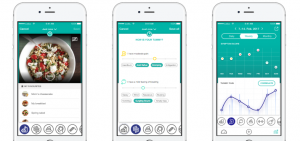

The first step of a daily log would involve selecting what the user ate, from a large database of foods. Next the user is asked to log other categories, such as pain level, bloatedness and stress. Cara then uses this data to correlate what foods link with high pain levels for example. Or assesses if stress is a factor that produces certain symptoms. With the users input, Cara can provide valuable insights and can also be exported for further medical use. (Cara Fast Facts, 2017).

What is new about Cara?

Cara has been able to develop an algorithm that combines the user’s “individual microbial, lifestyle, environmental and treatment response data” (Henriques, 2017). Brinkmann explains that there are no competitors out there with the ability to offer “appropriate medical remedies”. Carauses algorithms that continuously learn about their users to offer tailor made and individually relevant solutions, this increasing the effectivity of potential treatment (Comstock, 2017).

This development can be seen as a breakthrough in medicine in the area of digestive health, as it is often very difficult and time consuming for doctors to create and analyse data of individual patients who suffer from digestive problems (Henriques, 2017). With this possibility doctors are better able and can help faster to try and solve the patients symptoms.

“Digestive issues are still a taboo topic but we are now making them visible to the public” (Comstock, 2017) says Brinkmann. The app makes digestive issues a more neutral and open topic that should be taken seriously. By connecting digestion to mundane topics such as eating and sleeping for example, it becomes less of an issue for patients to be ashamed of.

Self-Tracking

Today it is common to self-track, which simply suggests that individuals measure certain things about themselves (Swan, 2013). These things can be any “biological, physical, behavioural or environmental information” (Swan, 2013). Lupton in her book The Quantified Self (2016) describes self-tracking as a way of self-reflection that is meant to lead to some kind of positive improvement or goal. Self-tracking is not just the gathering of personal data but users take a proactive stance to react to the information according to Swan writer of the journal article Quantified Self: Fundamental Disruption in Big Data Science and Biological Discovery (2013). Self-tracking media are not exclusive to health, however people do mainly want to focus on mental and physical performance enhancement (Swan, 2013). Counting in the year 2017 there are over 40,000 smartphone apps available that allow people to track themselves (Swan, 2013). To illustrate how common self-tracking is, 60% of adults in the U.S.A. are tracking their weight, nutrition or exercise routines. (Swan, 2013).

Blogger Christina Stiehl conducted a small experiment with herself out of curiosity of these self-tracking trends. She downloaded a series of apps on her phone to track different aspects of her life such as; exercise, nutrition, mood, alcohol consumption, her menstrual cycle and even her pee and poop. In her search of seeking if she could indeed reach her full physical and mental potential she described her time as a devoted self-tracker as “annoying” more than it being a life-enhancing activity. Self-tracking includes recording extremely personal information and Stiehl also describes that there was a “creepiness factor […] When it comes to mood, urine, faeces, menstrual cycle and sex life, well, there are some things better left alone, out of sight, out of mind, and off my phone” (Stiehl, 2016).

The Quantified Self

The quantified self can be seen as a term to describe the movement of people engaged in self-monitoring practices and refers to using numerical data to measure aspects of everyday life (Lupton, 2016). The movement has emerged from the self-tracking culture and is a phenomenon that is growing and moving from our personal lives to larger social contexts, such as healthcare (Lupton, 2016).

Democratization of Medicine

Lupton suggests that self-tracking has spread from the domain of the individual meaning that where it used to be a personal and private choice to keep track of your activities, it is now becoming more common for people to be encouraged or ‘nudged’ towards self-tracking media. “Arguments for persuading patients with chronic illnesses to engage in self-tracking […] are becoming increasingly common in the medical literature” (Lupton, 2016). Swan does explain that research has shown that “many self-trackers have found implementable solutions in areas that the traditional health system would have never have […] applied to their specific care”. These points of discussion link in nicely with the introduction of apps such as Cara. The makers of Cara claim that a whole group of the population of the world (those with chronic digestive problems) would otherwise not have access to solutions to their problems, as Swan suggests. Sharon, the writer of Self-Tracking for Health and the Quantified Self (2017) explains how healthcare is moving away from a “one size fits all” approach and embracing the possibilities of self-tracking technology which can provide a way to help patients on a more personalized level, creating personalized healthcare solutions.

Sharon explains how there is a change in mind-set of patients today with regard to healthcare and self-tracking, people are moving from “my health is the responsibility of my physician” towards “my health is my responsibility and I have the tools to manage it”. Again, Cara is an example of an application that allows patients to take matters into their own hands. Sharon however does argue that because patients are becoming more involved and informed about their treatment it gives them more empowerment within the doctor-patient relationship, this can is also described by Sharon as “participative medicine”. Cara also encourages this with the function where all the data collected can be extracted and used for further medicinal research or support with a doctor. Here the patient has obtained important information for their medical case themselves, which allows for a more informed discussion with their doctor. Sharon describes this shift in empowerment as the “democratization of medicine”.

Digitization is Normalization

Another widely debated topic is the digitization of self-tracking and along with that comes the issue of data privacy issues. People are becoming increasingly use to using self-tracking apps, thus finding it normal to share even the most intimate details about your mental and physical health. Sharon describes is as the “normalization of intrusive surveillance practices”, people are giving away their information on these apps and are becoming use to their intimate details being a piece of data on their phone. In the case of Cara, bowel issues were described as a taboo however the app normalizes it and takes some of the awkwardness away. But the question arises to what extent do we want all our information to be out there? Would you want others to be able to see into the records of your poop from the past few days?

A Paradox

All in all, like Swan suggests that the debates surrounding the quantified self is quite a paradox: on the one hand people are becoming increasingly dependent of technology, will physicians not be needed in the future? However on the other hand self-tracking has proven to give a more detailed, controllable and personal relationship with health, and people are also becoming much more informed. Cara is an example of this and has provided tailor made solutions for patients who would otherwise still be struggling. It is important to understand the effects of self-tracking, however we cannot deny its tremendous potential.

Bibliography

“Cara Fast Facts.” cara-app.com. N.p., 2017. Web. 24 Sept. 2017.

Cara. Image Cara App. 2017. Web. 24 Sept. 2017.

Comstock, Jonah. “Cara Gets $2M To Help IBD, IBS Patients With Tracking App, AI.” Mobi Health News. N.p., 2017. Web. 24 Sept. 2017.

Emberify. Image: Self Tracking In Medicine: Enhancing Healthcare. 2017. Web. 24 Sept. 2017.

Get Narrative. Image: How Not To Go Crazy Self-Tracking. 2017. Web. 24 Sept. 2017.

Henriques, Carolina. “Cara, First Precision ‘Poop Tech’ App For Digestive Health, Raises $2 Million In Seed Funding.” IBD News Today. N.p., 2017. Web. 24 Sept. 2017.

Lupton, Deborah. The Quantified Self. 1st ed. Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2016. Print.

Sharon, Tamar. “Self-Tracking For Health And The Quantified Self: Re-Articulating Autonomy, Solidarity, And Authenticity In An Age Of Personalized Healthcare.” Philosophy & Technology 30.1 (2017): 93-121. Web. 24 Sept. 2017.

Stielh, Christina. “I Tracked My Poop, My Period, And Everything In Between. Here’s What I Learned..” Thrillist. N.p., 2017. Web. 24 Sept. 2017.

Swan, Melanie. “The Quantified Self: Fundamental Disruption In Big Data Science And Biological Discovery.” Big Data 1.2 (2013): 85-99. Web. 24 Sept. 2017.