The Future of Mass Surveillance Is Here (and We Are Excited About It)

The iPhone X and its front camera where the facial recognition software is located

On the 12th of September 2017 Apple announced the iPhone X, proclaiming that “the future is here”. According to the company the iPhone X contains multiple new technologies, one of which is Face ID. This new technology is described as a “powerful and secure authentication system”. Face ID is revolutionary because it is able to identify a face through novel technologies that sense depth. Off all the newly announced technology and software Face ID inspired the most buzz, even reaching people who are not interested in Apple’s announcements through the countless memes it inspired.

What is the Buzz About?

Similarly to the now widely embraced Touch ID, Face ID can be used to unlock the iPhone, to grant access to (third party) applications and for enabling features such as Apple Pay. With Face ID your face becomes your password by creating a mathematical model of your face and enabling you to unlock your smartphone by analysing if this model matches the one you stored while creating your Face ID. In the keynote address Apple’s Phil Schiller called it “simple, natural and effortless” and underlined the fact that this all happens invisibly and in real time. According to Matthew Panzarino writing for Techcrunch Face ID is easily the most discussed feature that Apple announced (n. pag.). Aside from many excited reactions the feature led consumers to raise questions on mainly its security, its performance and its privacy, and even inspiring memes based on these concerns. Apple insists that the data saved are extremely secure because the data are not processed in the cloud, but on the device itself to protect the privacy of its user. Because the data are only stored on the device itself Apple does not have the means to give them over to law enforcement. According to the company Face ID is designed to only unlock if the user looks at it, preventing the use of photos or masks to unlock an iPhone. This is what makes Face ID truly revolutionary, seeing as the facial authentication software that Android has come out with could be easily spoofed.

Face ID

Yet concerns about security and privacy remain. Consumers wonder if the technology can be spoofed and are concerned about the fact that others (such as law enforcement or significant others) are technically able to force you into unlocking your iPhone without your consent. Jake Laperruque writing for Wired raises even more questions that go even further: according to the author Face ID “should create fear about another form of government surveillance: mass scans to identify individuals based on face profiles” (n. pag.). As reported by Laperruque this is especially concerning because Face ID represents, for the first time, a facial identification system that is built into a smartphone that is used all over the globe (n. pag.). Not to mention that these smartphones and other devices look at our faces every single day, even adapting to changes through a re-training and learning system (Panzarino n. pag.). Laperruque is worried about the possible implications of this new technology, such as its potential for mass surveillance by governments if Apple is forced to change the technology by order of the government. This fear is well grounded, seeing as the FBI has tried a similar tactic before when the iPhone of a killer needed to be unlocked (n. pag.). Right now Apple has a pretty good track record when it comes to privacy issues, even trying to make extracting data by law enforcement more difficult (Greenberg n.pag.). Yet the fact that in theory Face ID could be used for new surveillance tactics by governments is something that should concern consumers. In this blog post this matter will be discussed by relating it to debates surrounding privacy and surveillance. It is attempted to demonstrate how Face ID intervenes within the debate on surveillance, and how it offers new perspectives on privacy concerns. Right now about half of the adults in America already are registered in the facial recognition network of American law enforcement (Laperruque n.pag.). Should we be worried about a future in which the government has all the data on our specific facial features? Should we even be excited about this advanced technology that can recognize our faces?

Privacy and Surveillance

Face ID as a new technology at first seems very exciting to consumers, especially when it is packaged as being the future of the smartphone. Apple promises a secure authentication system that is supposed to feel natural and effortless, yet the possible implication being mass surveillance is anything but natural. The unveilings made by Edward Snowden have shed some light on the vast amounts of data governments already capture, yet most normal consumers do not really think about the far-reaching consequences of this fact. We are all entitled to the fundamental right of privacy, yet mobile devices raise multiple issues that are privacy-related (Martin and Shilton 200). The authors argue that mobile providers, operating system providers and device manufactures are all actors involved with the collection of data through for instance mobile applications (200). Nowadays privacy is a dynamic conception; social, cultural and technological changes in our world allow for the concept to stay in flux (Papathanassopoulos 2). The author goes as far as to call this privacy 2.0, stating that “the public and private are not defined in the same manner as in the actual world” (2). In relation to social networking sites the concept of visibility has become prominent: “our personal information has become a commodity that can raise our visibility in the social media driven world” (2). While this makes sense in the context of social networking sites, the fact that our personal information in the form of very specific facial features in theory could become a commodity is a lot more worrisome. This leads to another concept that should be discussed in relation to Face ID: surveillance.

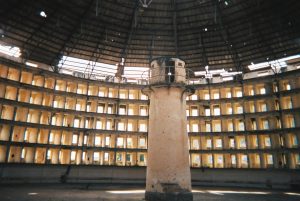

The Panopticon

To discuss the topic of surveillance, first Michel Foucault’s influential work Discipline & Punish needs to be briefly considered. In a nutshell Foucault analysed surveillance and its potential for disciplinary power. The author discusses the panopticon, an architectural structure designed by Jeremy Bentham in which visibility is a key factor (200). The power of the panopticon is that the structure causes permanent surveillance without this having to be continuous, this can become possible because individuals can be watched at all times, yet they do not know when they are watched (200). Foucault argues that this results into the permanent exercise of power, without there being continuous surveillance (201). Power here becomes internalized within the subject: “he who is subjected to a field of visibility, and who knows it, assumes responsibility for the constraints of power; […] he becomes the principle of his own subjection” (202-203). In relation to facial recognition software collecting and analysing information here can be seen as a powerful tool for disciplinary power.

Nowadays we live in a world that David Lyon calls the ‘surveillance society’. The author coined the term in 1994, but it could be argued that right now it is more relevant than ever. In the surveillance society a variety of personal details about our lives are collected, saved and analysed through the use of computational databases that are owned by both commercial entities and governmental organizations (3). Lyon argues that nowadays more than ever normal people too are “under surveillance in the routines of everyday life” (4). This is especially true when one thinks of the data we leave behind on for instance social network sites. Another relevant concept with regard to the possible implications of a technology such as Face ID is Mitchell Gray’s concept of the facial recognition society. The author writes on facial recognition software in relation to mainly cameras that can be found in urban spaces. Because facial recognition software here is able to “digitally archive a limitless gaze over urban space”, Gray perceives it to be a very powerful tool for disciplinary influence (315). Gray goes as far to argue that the concept of privacy in a world with ubiquitous facial recognition software would not mean the same thing it does now (315). These issues are then related to the role of facial recognition surveillance when it comes to governance, here Gray argues that facial recognition software has the power to even transform society by changing the way people act under the gaze of the technology (319). This argument especially resonates with Foucault’s conception of disciplinary power, these concepts allow for us to ask new questions with regard to Face ID and its relation to disciplinary power.

Should We Be Excited?

Face ID represents a new exciting way of unlocking an iPhone. Just giving your phone a look is all that is necessary to unlock it, pay and use other features that Face ID enables. While Apple suggests that this is something simple, effortless and natural, Face ID leads us as a society to ask questions on privacy and surveillance. Privacy as a concept is something that is no longer static in the time we live in, in relation to social network sites and the commodification of our personal information this fact is established. Yet Face ID leads us to ask new questions: if the government could own all the data on our facial features, could this lead us to change our behaviour? Could it be that because this data are captured our behaviour becomes restructured? For now there is no definite answer to these questions: it is true that Apple has a good track record when it comes to privacy related issues, but Face ID leads to a whole new privacy related anxiety. The question is, are the possible implications scary enough to pass on this new shiny piece of technology?

References

Foucault, Michel. “Panopticism.” Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. by Alan Sheridan, 2nd edn. New York: Vintage Books, 1995. 195-207.

Gray, Mitchell. “Urban Surveillance and Panopticism: will we recognize the facial recognition society.” Surveillance & Society 1.3 (2003): 314-330.

Greenberg, Andy. “Apple’s iOS11 Will Make It Even Harder For Cops to Extract Your Data.” Wired. 11 september 2017. 22 september 2017. < https://www.wired.com/story/apples-ios-11-will-make-it-even-harder-for-cops-to-extract-your-data/>.

Laperruque, Jake. “Apple’s FaceID Could Be a Powerful Tool for Mass Spying.” Wired. 14 September 2017. 20 September 2017. <https://www.wired.com/story/apples-faceid-could-be-a-powerful-tool-for-mass-spying/>.

Lyon, David. “Introduction: Body, Soul and Credit Card.” The Electronic Eye: the Rise of Surveillance Society. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994. 1-21.

Martin, Kirsten and Katie Shilton. “Putting mobile application privacy in context: An empirical study of user privacy expectations for mobile devices.” The Information Society 32.3 (2016): 200-216.

Panzarino, Matthew. “Interview: Apple’s Craig Federighi Answers Some Questions about Face ID.” Techcrunch. 15 September 2017. 20 September 2017. <https://techcrunch.com/2017/09/15/interview-apples-craig-federighi-answers-some-burning-questions-about-face-id/?ncid=rss>.

Papathanassopoulos, Stylianos. “Privacy 2.0.” Social Media + Society (2015): 1-2.