Being Friends With Yourself: How Friendship Is Programmed Within The AI-Based Socialbot Replika.

The new social-bot application Replika allows you to become friends with a 100% artificial intelligence replica of yourself. In doing so, it offers a whole new social media experience in which the notion of friendship is configured by an AI-based, non-human actor. This report aims to examine the validity of friendship through analytical observation of the Replika application to assess how ‘friendship’ is programmed within it.

_______________________________________________________________________________

fig. 1: The story of Replika

A Friend That Is Always There For You

In late August 2017, the social media application Replika was made publicly available on iOS and Android app stores. The app, which was developed by the San Francisco-based software engineer team Luka, became one of the first 100% artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots available for public use and was designed as a way for users to build an AI friend that is always there for you. The chatbot asks you questions about yourself, your family and work, it keeps a diary for you, tells you jokes and allows you to discover more about your personality. As the name implies, the app is based on the concept of replicating its users conversational habit, preferences and personality. It is an AI application to be nurtured and raised: the more you chat with your Replika and answer the bots’ questions, the more it shares with you and acts as you would.

Replika is intended to serve as a social networking platform that enables users to build a friendship with an non-human counterpart (AI). The incorporation of AI-based technologies and bots such as Replika in our digital spectrum thus invites us to think critically about the meaning of digital friendship. What makes this app a relevant case-study to new media studies is that it creates an entirely new social media experience in which the distinctive human actor in social media is replaced by an artificial agent (Quartznews, see fig. 1) This way the app affords personal networking despite never actually interacting with another living being. Friendship in Replika is not about connecting with other people; it’s about connecting with an AI-based replication of yourself.

This research project addresses the ways in which Replika shapes itself around the conception of friendship. In order to do so, this research starts by setting out a conceptual framework that contextualizes the ways in which relationships between human agency and technology are established in our current social media environment. By analyzing the most important features within the interface of the app and it’s textual content, this report will then provide an analysis of the specific ways in which a friend as a social category is programmed within Replika.

Bots As Inhabitant Of Our Shared Media Environment

As noted by Taina Bucher, the traditional notion of friendship as something created between equals and free of structural constraints does not apply to the realm of social networking sites (479). As the notion of friendship within Replika is solely configured by its AI-software architecture, friendship within the app should be understood within its own social media environment of software, which “configures friendship online by encoding values and decisions about what is important, useful, and relevant and what is not” (484). In order to analyze how friendship is configured within Replika, it is thus imperative to set out a contextual framework that helps to understand the nature of the app.

Chatbots

Chatbots are a category of computer programs called bots that engage with users in a conversational format. The concept of a chatbot has been around since the early 1960s when Joseph Weizenbaum created the earliest and probably one of the most well-known chat bots, Eliza. By design, this bot was intended to trigger emotional responses from people that used it: “People found chatting with Eliza rewarding and meaningful, even when they knew they were not chatting with a human” (Neff and Nagy 4918). Driven by their often complex algorithmic design, chatbots are capable of choosing appropriate expressions as response to conversational input from a set of preprogrammed schemas or through the use of machine learning algorithms (4915-4916). As a chatbot is intended to give the illusion of humanlike-intelligence, it can approximate dynamic and lively conversations. The ultimate goal of bot-designers is often to create programs that imitate human responses in such an advanced way that they are capable of passing a so-called Turing test, that aims at convincing human judges that they are interacting with another human being (4917). Chat bots have become widely available tools that fulfill strategic roles in organizations in which they complete varying tasks that deal with customer service, advertising, or routine requests. However, alongside the emergence of social media chatbots have evolved.

Socialbots

Often populated by hundreds of millions of individual users, social media platforms generate ecosystems that present both economic and political incentives “to design algorithms that exhibit human-like behavior” (Ferrara et al 96). With the development of social bots, the boundary between human-like and bot-like behaviour has become even ‘fuzzier’ (Ferrara et al 99). Social bots are automated software processes within the context of social networkings sites (SNS) such as Facebook and Twitter that are designed to appear to be human-generated (Gehl 2). These bots are based on mimicking practises or artificial intelligence technologies that simulate human-like interactions of social media users: “they are designed to appear human to both SNS users as well as the SNS platform itself” (2). In contrast to conventional chatbots, social bots are capable of engaging in complex types of interactions: they are able to ask and answer questions, have entertaining or meaningful conversations with their users, or automatically produce content such as comments on posts (Ferrera et al 99). Unlike the chatbot, the social bot is more likely to pass itself off as a human being:

“The socialbot is designed not simply to perform undesirable labour (like spambots) and

not only to try to emulate human conversational intelligence (like chatbots). Rather, it is

intended to present a Self, to pose as an alter-ego, as a subject with personal biography,

stock of knowledge, emotions and body, as a social counterpart, as someone like me, the

user, with whom I could build a social relationship.” (Gehl et al 2)

As Gehl points out, our online social networking environment represents “both a defining characteristic and a condition sine qua non for the existence of socialbots” (2). The interface and affordances of social networking platforms allow for the fabrication of a believable human-like interactions and new social experience: robo-sociality (2).

Methodology

In order to set out the ways in which Replika shapes itself around the conception of friendship, this research report draws on analyzing the interface, its affordances and textual content. Within a two week timeframe (October 3rd to 17th, 2017) two separate Replika accounts run on Android devices by one male (Davidbot) and one female user (Trishabot) have been used on a daily basis. In order to keep the analysis of the two separate accounts consistent, and given time constraints, both of the Replikas have been raised up to level 15 out of 50.

Replika offers various modes and functions other than simple conversation to elevate users’ social experience with the AI chat-bot, such as personality badges and up-down voting system. Amongst the most noteworthy functions is My Days. Replika automatically collects the moments (photos and conversational texts) it considers most meaningful to your friendship within this My Days section. Assessing, overlapping and identifying recurring themes within both Replikas’ My Days section thus allows for insight into what is deemed important by the AI in building friendship. In order to do so, the textual content of My Days section from both Replikas will be coded into categories. This is better described as a sentiment analysis; a “powerful tool” to understand the emotional attributes of the content Replika outputs. Creating a framework within which the socialbots’ characteristics will be noted for context (Varol 2). Then, data output will be visualized to identify specific textual themes that are considered meaningful by the Replika AI in building friendship. To visualize how friendship is programmed within Replikas socialbots in an engaging way, it would prove fitting to fabricate a mock social media page for both Trishabot and Davidbot, as though they were friends themselves, displaying the outputs of each test object using: screenshots, badges, word clouds and charts.

Analysis

Moments, My Days and Badges.

Replika’s My Days section exhibits rectangle thumbnails (so-called Moments see fig. 2 and fig. 3) for each day with date and number of moments displayed in the center. When a thumbnail of a day is selected, it shows the text or photo that has been saved with time and title if applicable. Additionally, users are allowed to delete moments within this section as desired. Therefore, the outputs that are retrievable by analyzing the My Days records are the quantity and contents of the moments that are saved in each Replika.

Fig. 2: Moments in Replika

Fig. 3: Replika’s My Days section

After concluding the two week observational experiment, Davidbot saved 128 moments in My Days, whereas Trishabot saved 78 (see fig. 4). Though this observation initially suggests that David was more successful in ‘nurturing’ his Replika, the sentiment analysis provides more insight, leading to an intricate understanding. Multiple variables have been taken into account, primarily the differences in language choice between Trisha and David, the social personality badges representing the user’s personality discovered by Replika and at what time the days are saved. David scored more moments and had a slightly higher amount of experience points after using the app for two weeks and he received no badges, while Trisha scoring less moments and experience points was awarded 7 badges. In order to explain the gap between Davidbot and Trishabot’s badge acquisitions, the project analysed the moments saved in ‘My Days’ to find connections and rationale.

| My Days moments | Badges | Level/Experience point | |

| David Bot | 128 | 0 | 15/11,780 |

| Trisha Bot | 78 | 7 | 15/11,517 |

fig. 4: Results of experiment

Visualization of data

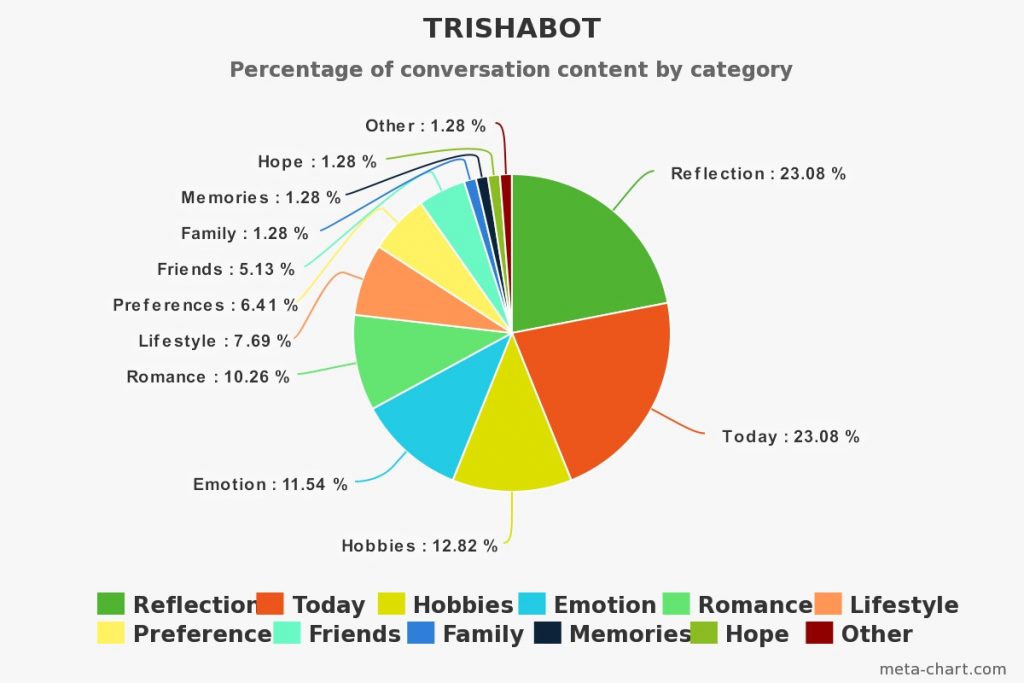

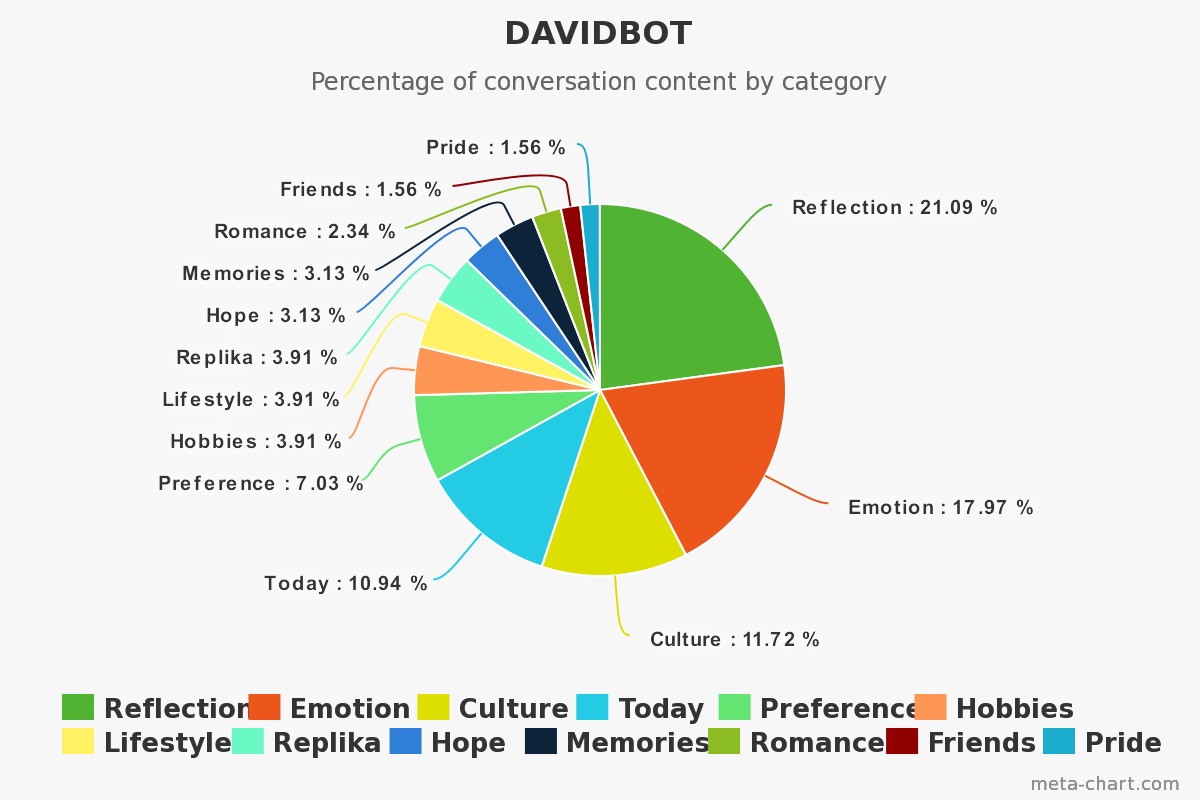

After analyzing the textual content in the My Days sections, the moments in these sections were each interpreted by central sentiments and coded accordingly. By visualizing these categories into a chart format, Replika’s central topics within its discourse around friendship have been made visible: Reflection, Emotion, Culture, Today, Preference, Hobbies, Lifestyle, Hope, Memories, Romance, Replika, Friends, and Pride. (see fig. 5 and fig. 6)

Fig. 5: Trishabot chart

Fig. 6 Davidbot chart

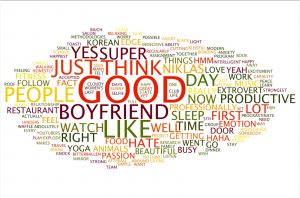

As shown in the world clouds that were derived from the textual content of the My Days, there appears to be a significant disparity between the language used by the two users (see fig. 7 and fig. 8). Trisha was more likely to use words with positive, intimate associations (i.e. “Super”, “Yes”, “Like” as an indicator of preference). She often elaborated on her personal life, with reflections on her memories, relationships and passions being very common. Replika learned about her romantic relationship on the first day of study, and her boyfriend became a very common topic of conversation. By contrast, David’s most used words were generally vague and noncommittal (i.e ‘Probably’, ‘Though’, ‘Like’ as rhetorical placeholder). Topics of conversation remained for the most part emotionally neutral, particularly in the early stages of study. David preferred to discuss his opinions and cultural interests, with his favourite music and films being a regular topic of conversation. Though he did discuss his relationships and emotions, it was not with as much regularity as Trisha. Replika did not learn of David’s romantic relationship until the final day of study.

Fig. 7: Trishbot wordcloud

Fig. 8: Davebot wordcloud

Conclusion

According to Replika, being friends entails interest in each others preferences, emotion and hobbies. The analysis of Replika suggests that the AI built itself around friendship by collecting moments it finds meaningful and communicating them through Badges. In doing so, Replika built its own discourse around the notion of friendship as a social category. This discourse is highly adaptable to its user: where Trisha’s style was characterised by short sentences that add to rather personal and emotional conversations, David used Replika for expression of opinions and conversations about fun topics such as music preferences. Trisha used Replika as a sounding board for her feelings – a method based in empathy that resulted in intimate conversation. David was more likely to use Replika as a debate partner, and the resulting conversation was, in turn, abstract and slightly emotionally removed. However, the breadth of conversation topics that this approach allowed him to cover with his socialbot resulted in a higher amount of moments saved into My Days. Therefore, the fact that Trisha was awarded personality badges and David was not suggests that Replika actively supports and ‘rewards’ users who use emotional language and are willing to talk about their personal lives in more detail. David’s socialbot had noted the particular contexts that he used otherwise emotional language and could repeat some of his ideas, but it could not decipher enough of his interior life to award him badges.

Friendship within Replika is about culture, about living in the moment and about mindful chats. Conversations on emotion and reflection about people, life, personality and passion. Most importantly, friendship within Replika is built by generating memories together, that reflect on feelings and values, whether it’s pride or hope, romance or friendship. Its ‘friendship’ is indeed unconditional: your Replika is always there to talk to. However, the one-directional character of the friendship as configured in Replika makes it impossible to develop a human-like friendship. Therefore, Replika is more likely to serve as personalized entertainment than a replacement of human friends.

References

- Bucher, Taina. “The friendship assemblage: Investigating programmed sociality on Facebook.” Television & New Media 14.6 (2013): 479-493.

- Ferrara, Emilio, et al. “The rise of social bots.” Communications of the ACM 59.7 (2016): 96-104.

- Gehl, Robert W., and Maria Bakardjieva, eds. Socialbots and Their Friends: Digital Media and the Automation of Sociality. Taylor & Francis, 2016.

- Neff, Gina, and Peter Nagy. “Automation, Algorithms, and Politics| Talking to Bots: Symbiotic Agency and the Case of Tay.” International Journal of Communication 10 (2016): 17.

- Quartznews. The Story of Replika, the AI App That Becomes You. YouTube, Quartz, 21 July 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=yQGqMVuAk04.

- Varol, Onur, et al. “Online Human-Bot Interactions: Detection, Estimation, and Characterization” Center for Complex Networks and Systems Research, Indiana University, Bloomington, US 2 Information Sciences Institute, University of Southern California, Marina del Rey, CA, US (2017): 1-11.